Twenty Years After Nam June Paik

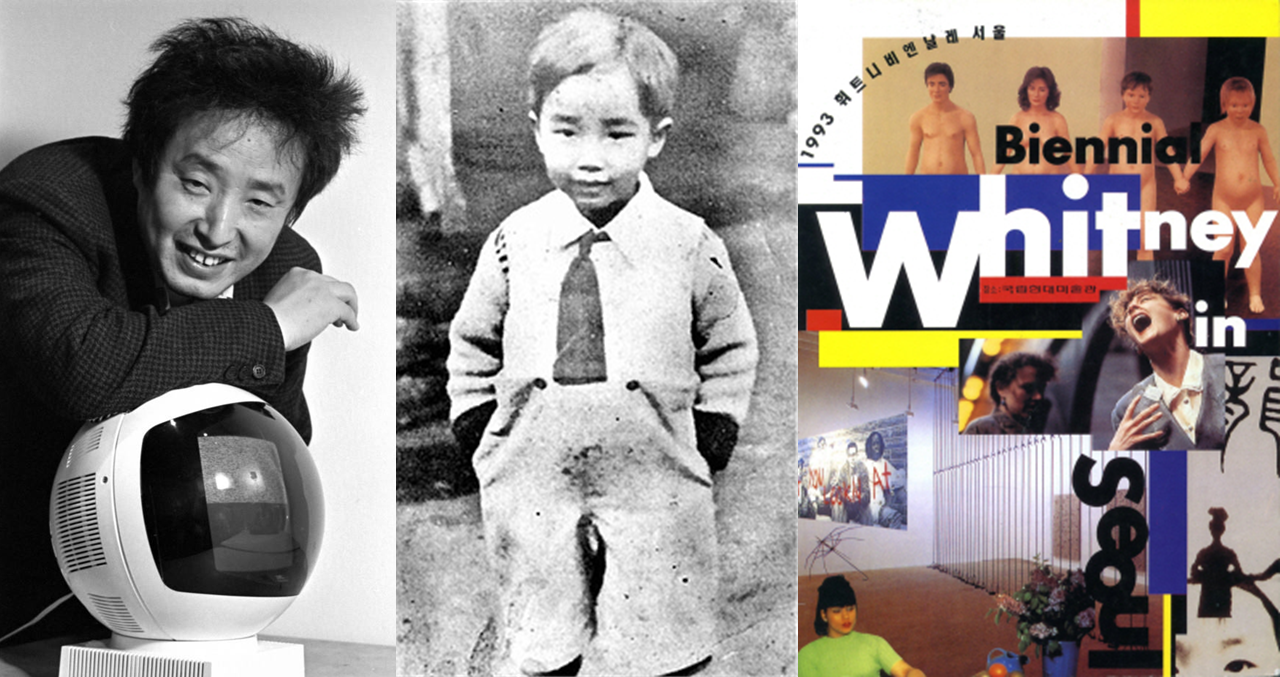

The year 2026 marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of

Nam June Paik (1932–2006).

Long before the emergence of the World Wide Web, Paik

envisioned a globally networked society. In 1974, he began conceptualizing Electronic

Superhighway, anticipating the cultural and social

transformations that digital networks would bring. As early as 1964, he

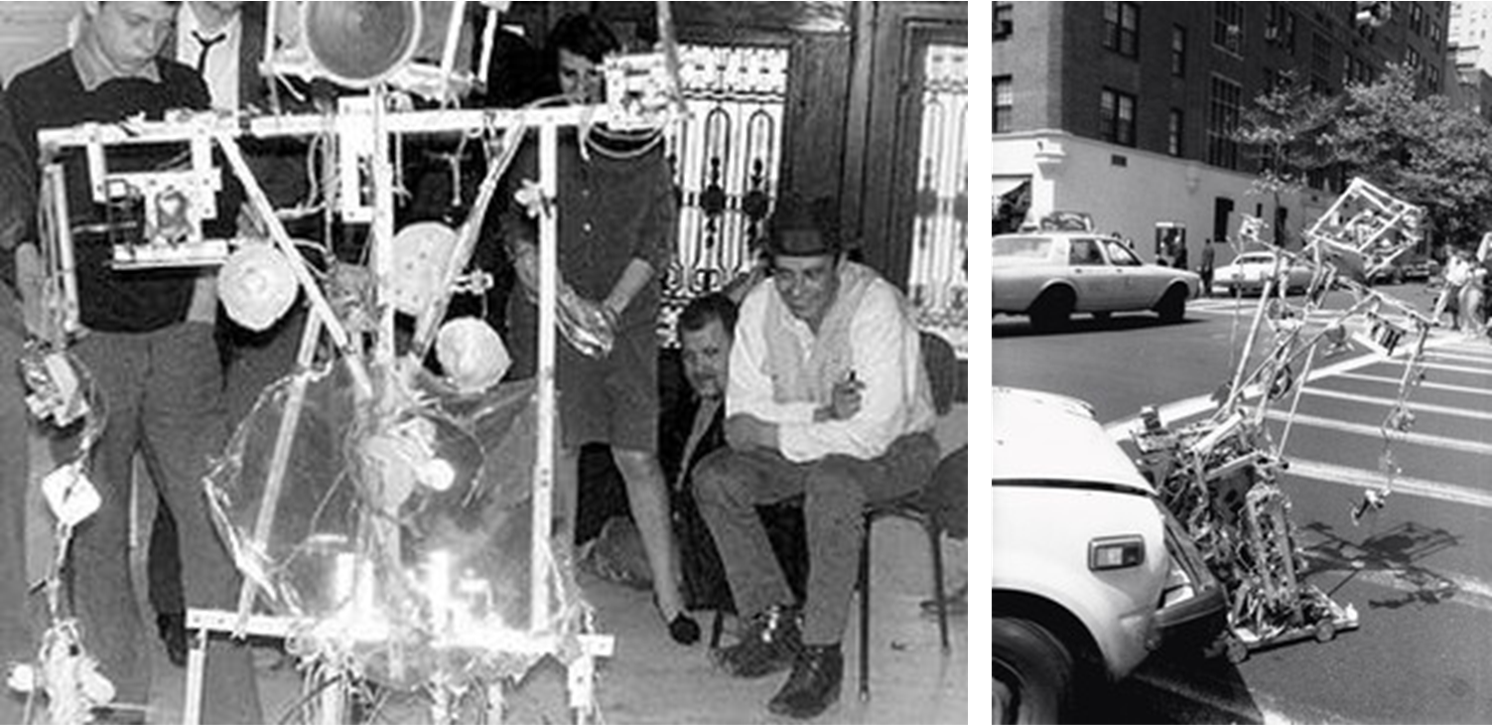

introduced Robot K-456, bringing the relationship

between humans and machines into the realm of artistic experimentation.

Robot K-456 staged a “traffic accident”

performance during Paik’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art

in 1982. The scene presented the machine not as a symbol of technological

progress, but as a being capable of experiencing life and death. Through this

gesture, Paik offered a powerful metaphor for the human condition within

technological civilization. In an era defined by artificial intelligence and

automation, this work resonates with renewed urgency.

To mark the 20th anniversary of Paik’s passing, institutions

in Korea and abroad are revisiting his legacy. The Nam June Paik Art Center is

currently developing the “AI Robot Opera project”, centered on Robot

K-456, in collaboration with artists including Byungjun Kwon.

Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art in Gyeongju continues its Nam June Paik

exhibition, first opened last year, through May.

(Left) Nam June Paik, Robot K-456, 1965 / Photograph: Hanns Sohm | © Nam June Paik, (Right) Staged accident with Robot K-456 in front of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1982. Photo: courtesy Nam June Paik Estate

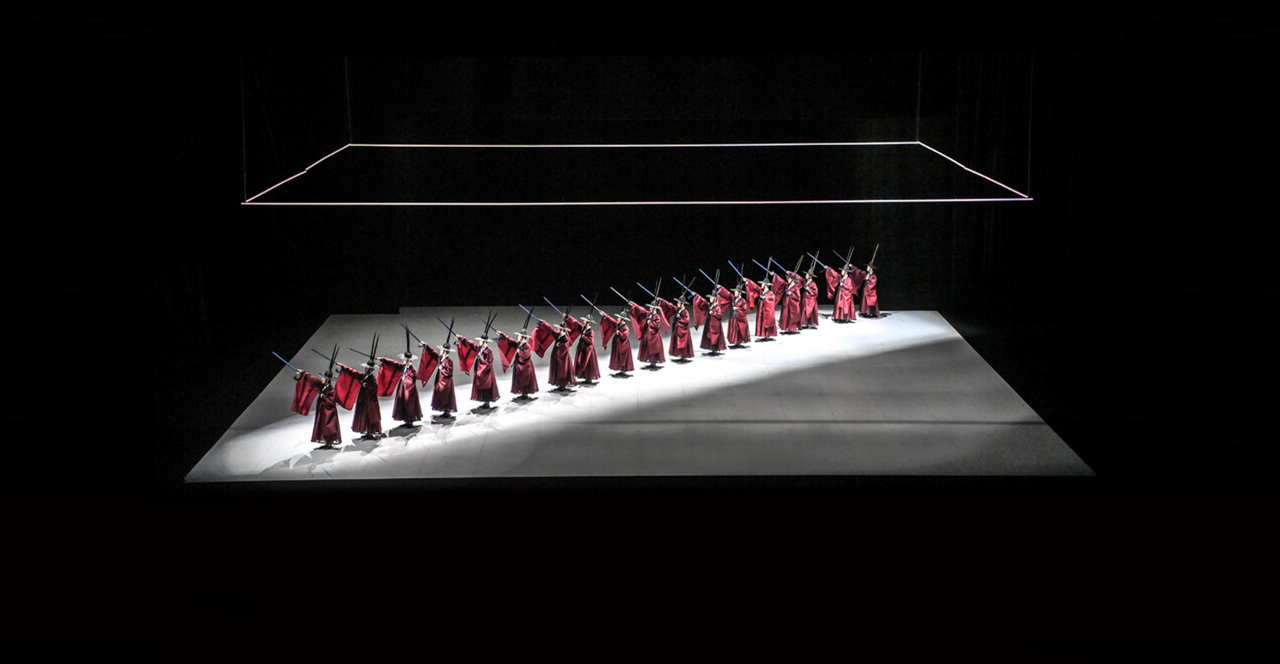

(Left) Nam June Paik, Ancient Horseman, 1991 / Photo courtesy: Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art, (Right) The Fractal Turtle Ship exhibited at the 1993 Daejeon Expo. In the background, another TV work by Nam June Paik, Madame Curie, is visible. / Photo: Daejeon Museum of Art

Amorepacific Museum of Art will present Paik’s large-scale

work Turtle Ship in its upcoming collection

exhibition this April. Meanwhile, the Getty Research Institute has launched a

research collaboration with the Arts Council Korea (ARKO), and in November, the

Nam June Paik Art Center and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo will jointly present

an exhibition supported by Hyundai Motor Company’s “Hyundai Translocal

Series”. Together, these initiatives signal a renewed global engagement

with Paik’s work.

Whitney Biennial New York 1993

The “Whitney Biennial 1993”, held in New York, was more than a single exhibition; it marked a critical turning point within the American art institution. Departing from traditional emphases on painting and sculpture, the biennial foregrounded video, installation, performance, text-based, and research-driven practices. The exhibition positioned social conflict and institutional critique at its core.

At the time, the exhibition faced harsh criticism for being

“overly political” and “lacking aesthetic pleasure”, becoming one of the most

controversial biennials in Whitney history. Yet this criticism precisely

captured the exhibition’s significance: it declared, at an institutional level,

that contemporary art could no longer operate on the basis of shared taste or

stable aesthetic standards.

Many of the exhibition formats now commonplace in museums—discourse-driven curating, identity politics, and research-based practices—can be traced back to the radical decisions made during this period. In this sense, the “Whitney Biennial 1993” was not a problematic past, but a formative moment shaping the conditions under which contemporary art institutions operate today.

(Left) Installation view of the

“Whitney Biennial 1993” Exhibition (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,

February 24–June 20, 1993). Ida Applebroog, Marginalia series (1992);

Ida Applebroog, Jack F: Forced to Eat His Own Excrement (1992);

Ida Applebroog, Kathy W.: Is Told that If She Tells Mommy Will

Get Sick and Die (1992). / Photograph by Geoffrey Clements, (Right)Installation view of the “Whitney

Biennial 1993” Exhibition (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,

February 24–June 20, 1993). From left to right: Charles Ray, Family

Romance (1992–93); Peter Cain, EP 110 (1992);

Peter Cain, Pathfinder (1992–93).

Photograph by Geoffrey Clements

(Left) Installation view of the

“Whitney Biennial 1993” Exhibition (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,

February 24–June 20, 1993). Ida Applebroog, Marginalia series (1992);

Ida Applebroog, Jack F: Forced to Eat His Own Excrement (1992);

Ida Applebroog, Kathy W.: Is Told that If She Tells Mommy Will

Get Sick and Die (1992). / Photograph by Geoffrey Clements, (Right)Installation view of the “Whitney

Biennial 1993” Exhibition (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,

February 24–June 20, 1993). From left to right: Charles Ray, Family

Romance (1992–93); Peter Cain, EP 110 (1992);

Peter Cain, Pathfinder (1992–93).

Photograph by Geoffrey Clements

“Looking Back: 1993” with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Massimiliano Gioni. Saturday, February 23, 2013, 3–4:30pm, at New Museum

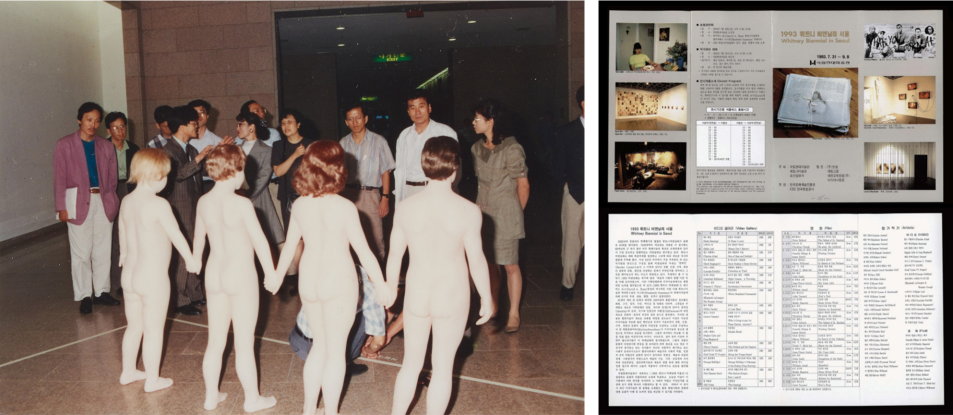

Whitney Biennial Seoul 1993

That same year, the Whitney Biennial was presented in Seoul

at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, under the

title《Beyond

the Border Line》. This marked the first overseas

presentation in the history of the Whitney Biennial.

The Seoul presentation was not a simple act of international exchange or a high-profile exhibition import. It immediately generated both attention and resistance. Public discourse questioned whether such works could even be considered art, while critics described the exhibition as difficult, inaccessible, and excessively political. Some questioned why a national museum should host such an exhibition at all.

Yet this friction was not incidental. The Seoul exhibition was designed not to provide comfortable viewing, but to confront the Korean art world with forms of contemporary art it had largely avoided. At stake was not merely the question of “what is art,” but whether Korean institutions were prepared to engage with contemporary art as it was unfolding globally.

(Left) Poster for the “Whitney Biennial Seoul”, held at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, Gyeonggi Province, in 1993. / Photo : courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, (Right) Performance Loving Care by American artist Janine Antoni at the opening of the 1993 “Whitney Biennial Seoul” / Photo: MMCA Research Center

(Left) Opening view of the 1993 “Whitney Biennial Seoul" / Photo: MMCA Research Center, (Right) Leaflet and event guide from the “Whitney Biennial Seoul 1993” © National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

Opening view of the “Whitney Biennial Seoul 1993”, with Nam June Paik on the right / Photo : MMCA Research Center

What Paik Brought Was Not ‘Achievement’,

but ‘Risk’

The driving force behind bringing the Whitney Biennial to

Seoul was Nam June Paik himself, who even contributed personally to the

transportation of artworks. What he introduced was not the established

achievements of American art, but contemporary art at its most uncertain and

contested.

The Whitney Biennial was never meant to present finished

results. It functioned as a platform for testing emerging practices whose

outcomes were far from guaranteed. Paik believed that Korean art needed to

think within the same temporal and risk-laden conditions as global contemporary

art.

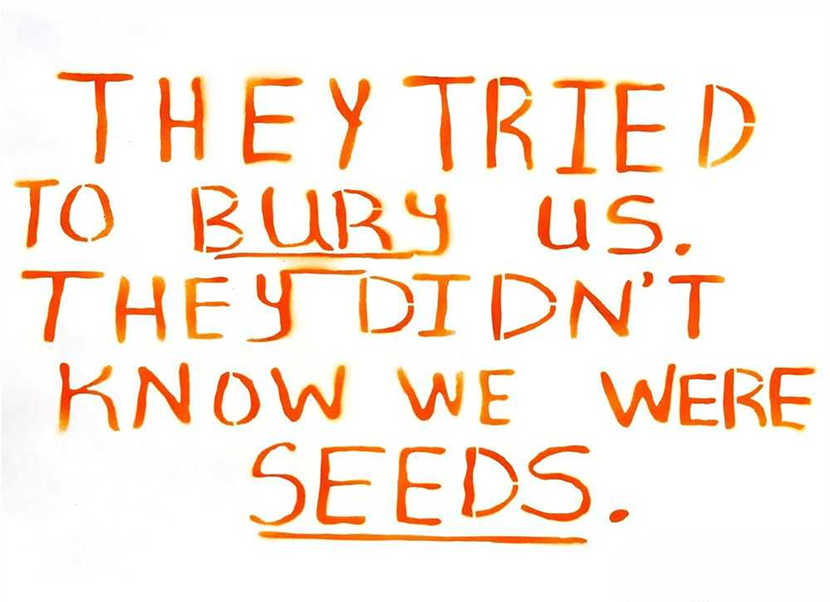

In a newspaper column written in August 1993, Paik made this

intention explicit. The exhibition was not meant to provide pleasure, but to

narrow the information gap and confront uncertainty directly. He famously

stated that the exhibition was not meant to offer young artists “delicious

food,” but to give them “strong teeth” capable of breaking any food. It was a

call for judgment, not protection.

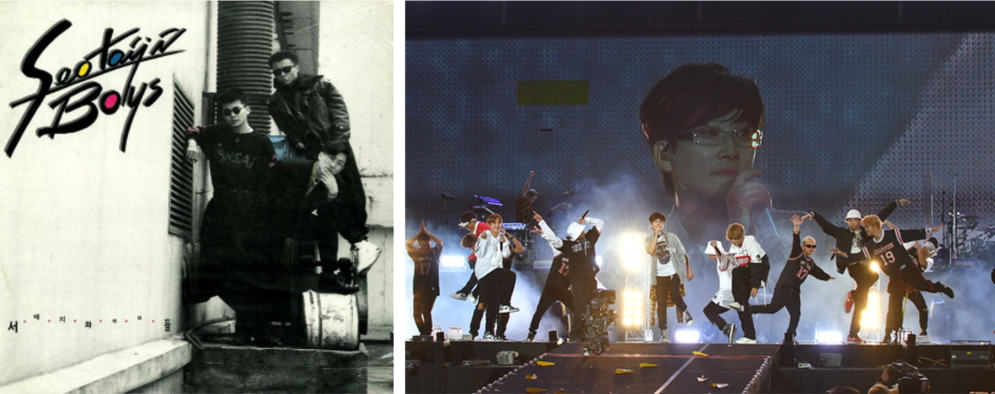

Choice as Cultural Structure

In the early 1990s, Korean society was undergoing a major

cultural transition. Popular music, following the emergence of Seo Taiji and

Boys, moved beyond imitation of Western pop and toward a self-sustaining

creative ecosystem.

This transformation was not the result of safe choices, but of accumulated risk and controversy. Cultural leadership does not emerge from avoiding failure.

(Left) Seo Taiji and Boys, 1st Album “I Know” (1992), (Right) Seo Taiji performing with BTS on stage / Photo: Seo Taiji Company

Reenactment of “Classroom Idea” from the 1995 concert “Another Sky Opens” / Photo: Seo Taiji Company

What Choices Is Korean Contemporary Art Making Today?

Today, Korean contemporary art operates under far more favorable conditions than in the past. Korean artists are regularly invited to major biennials and international museums, and institutional infrastructures have improved significantly. Yet favorable conditions alone do not guarantee contemporaneity.

Repeatedly importing already canonized artists and completed narratives may offer stability, but it also limits the institutional space available for emerging questions and experiments. This is not simply a programming issue; it concerns how Korean art participates in global art history as a present-tense practice.

Paik’s Enduring Legacy

When Paik brought the Whitney Biennial to Seoul in 1993, it was difficult, uncomfortable, and controversial. Yet it was precisely through this discomfort that the exhibition fulfilled the conditions of contemporaneity. Paik did not present a finished world; he demanded judgment amid uncertainty.

Recently, public art museums have been busy importing renowned international artists and exhibitions. While it's certainly important for the general public to enjoy culture and visit art galleries, it's even more crucial to support and produce indigenous Korean art and share it with the world.

Museums are not spaces for simply displaying objects. They are interpretive arenas that define which questions are allowed to occupy the center of contemporary art. What is chosen and what is excluded ultimately shapes the art history of a society.

Twenty years after his passing, the question Paik posed through the Whitney Biennial Seoul remains urgent. Are we still seeking comfort in completed narratives, or are we prepared to confront the unresolved issues of our time?

“There is uncertainty without creation, but there is no creation without uncertainty.”