President Lee

Jae-myung recently emphasized that “in the international society of the 21st

century, culture is at the core of national prestige and national power,”

adding that “even an additional supplementary budget should be

arranged if necessary to restore and strengthen the foundations of culture and

the arts.”

This statement

should not be read simply as a call for increased funding. Rather, it signals a

deeper question about the stage at which Korea’s cultural policy currently

stands. At a time when “K-culture” is receiving unprecedented global attention,

the recognition that the foundations of culture and the arts are in fact drying

up is particularly significant.

For this

awareness to lead to meaningful policy change, however, a more fundamental

examination must first be undertaken—one that asks what the current support

system is failing to address.

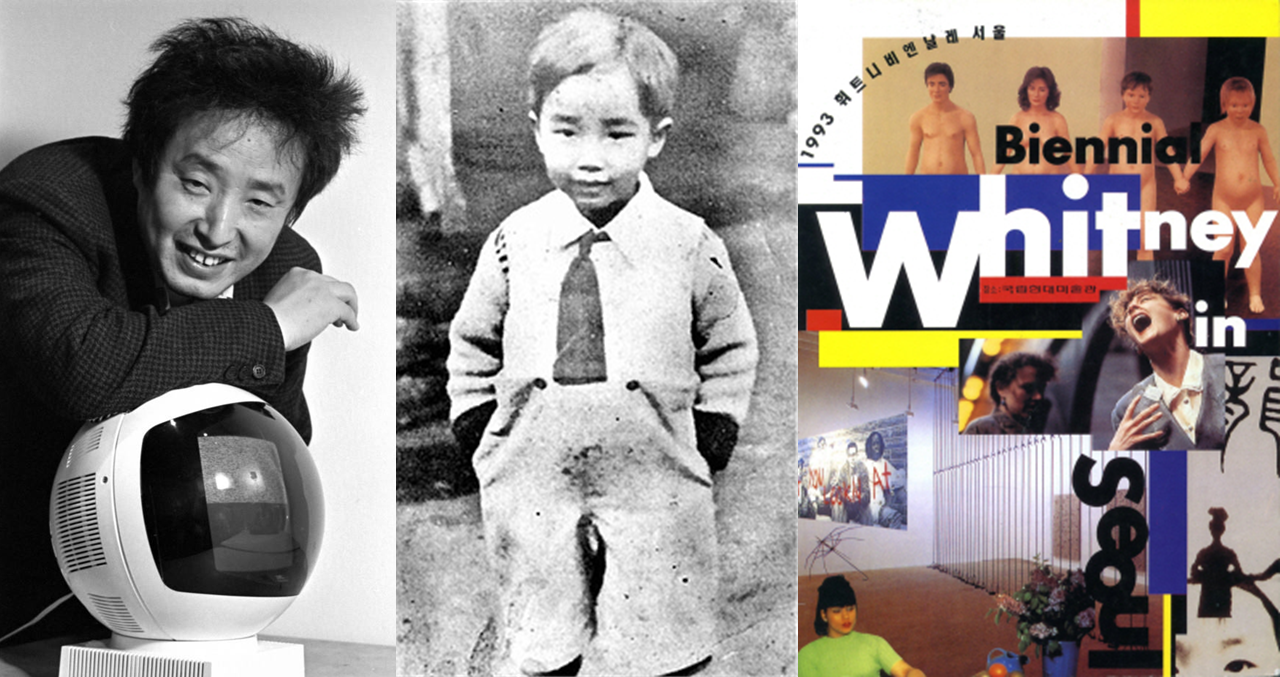

Screenshot from “The Guardian” article on the Korean film crisis

A recent article

in “The Guardian”, titled 「Almost collapsed:

behind the Korean film crisis and why K-pop isn’t immune」, offers a sober diagnosis of the

contradictions within Korea’s cultural industries. While Korean cultural

content enjoys overwhelming success in global markets, both film and K-pop

domestically are experiencing structural weakening. According to the article,

survival strategies driven by short-term results are instead eroding the very

ecosystems that make creative production possible.

In Korean cinema,

audience numbers and production volumes have plummeted, and the foundation that

once supported mid-budget films and emerging directors has nearly collapsed.

K-pop, meanwhile, has been reorganized around global tours and core fandoms, pushing

smaller agencies—once responsible for experimentation and diversity—to the

brink of survival. In both industries, only the sectors that directly

generate measurable results remain, while the structures that once enabled

those results are disappearing.

This situation

mirrors, with striking precision, the reality of Korea’s contemporary art

scene.

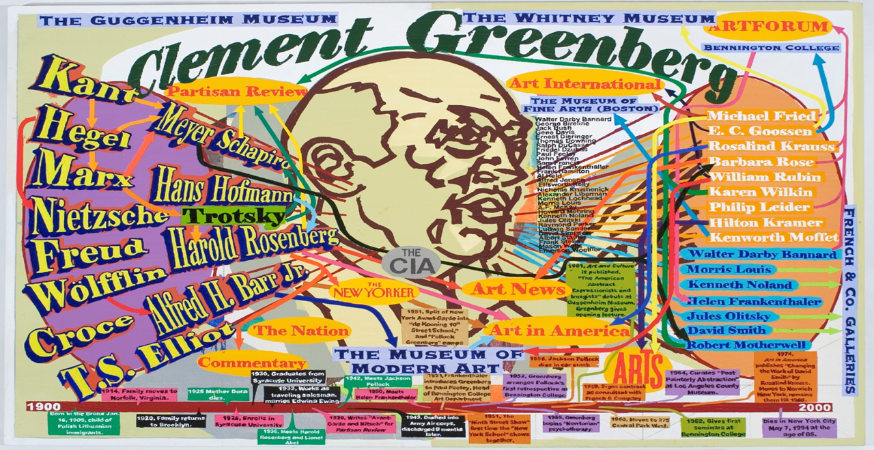

Why Is Support

for the Development of Fine Art Always Deferred?

Korea’s public

cultural policy and support systems have repeatedly been designed around

visible achievements, quantifiable outcomes, and overseas expansion. The

problem is that such criteria fundamentally conflict with the way fine art

actually functions.

Fine art does not develop on

the premise of short-term results.

An artist’s language emerges through long

periods of failure and accumulation, through repeated cycles of criticism and

interpretation.

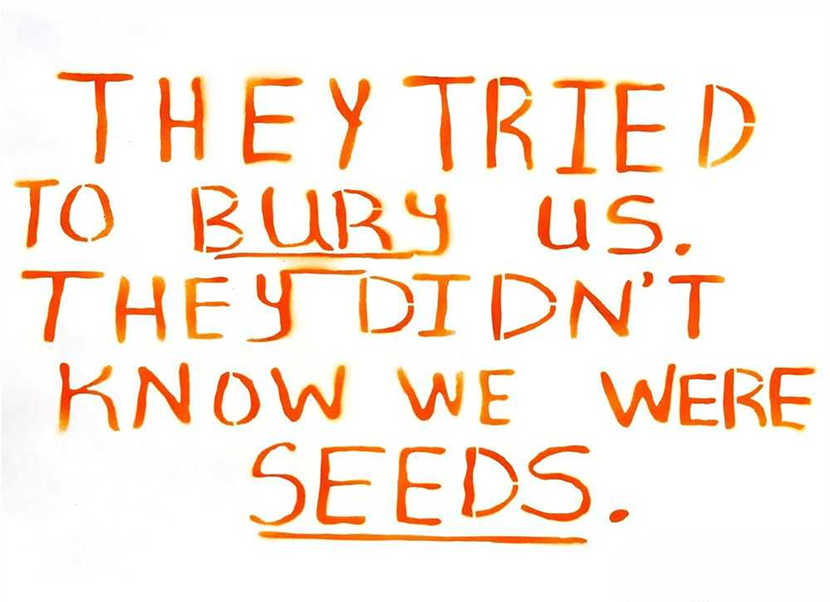

Seeds must be planted, roots must take hold, and soil must be

sustained before any fruit can appear. Yet the current support structure

concentrates resources only at the moment when results become visible,

investing little in the seed and root stages that make those results possible.

This pattern is

not characteristic of culturally advanced societies, but rather of societies

where culture is treated purely as a consumable outcome. It is a typical

symptom of systems that ignore conditions of production and long-term

accumulation.

View of the Arts Investment Workshop hosted by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the Arts Management Support Center

Source: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism · Arts Management Support Center

When

Distribution, Startups, and Global Metrics Replace the Purpose of Support

Over the past

several years, public support for contemporary art in Korea has shifted from

the language of “support” to that of “performance management.” The Arts

Management Support Center has positioned market research and statistics on

distribution sectors—galleries, auctions, and art fairs—as the policy

foundation for “fostering the visual arts industry and revitalizing the market.”

Across numerous programs, indicators such as the number of negotiations,

participants, transactions, and overseas buyers are accumulated as

representations of policy success.

International

distribution platforms operated or supported by the Center are explicitly

labeled as “markets” (such as PAMS), and event outcomes are frequently

presented in terms of numerical indicators like deal counts.

The issue here is

not distribution or market activation in themselves. Rather, it lies in the

fact that distribution metrics have begun to replace the fundamental purpose of

arts support. Questions central to fine art—what an artist’s work accumulates

over time, what kind of language it forms, and how that language connects to

criticism, exhibitions, archives, and collections—are pushed to the margins of

policy design. As a result, public support becomes less about supporting

artists and more about reproducing results in standardized, measurable forms.

When Programs

Take Precedence over Ecosystems

The Korea Arts

Council has likewise operated under constant pressure to translate support

systems into “evaluable results.” Public evaluation reports on the Arts and

Culture Promotion Fund have themselves pointed out problems such as

oversimplified performance indicators and weak causal links between project

goals and evaluation criteria. In other words, structural conditions are in

place where indicator management takes precedence over the original intent of

support.

Arts Council Korea Headquarters, Naju

Within this

environment, public funding tends to favor short-term, trend-driven programs

rather than long-term foundational development. Calls for proposals emphasizing

online platforms or technology-based creation frequently promise to build “new

ecosystems” by spanning creation and dissemination.

Yet while such

programs may be effective at producing visible results under the banner of “innovation,”

they remain structurally insufficient to guarantee the long-term accumulation

required by fine art—deepening artistic practice, refining critical language,

sustaining networks among artists, curators, and researchers, and

systematically linking archives and collections.

The Expansion

of Startup and Investment Frameworks, and the Marginalization of Fine Art

Programs such as

the “Arts Industry Academy” and “Early-Stage Arts Startup Support,” operated by

the Arts Management Support Center, translate art into the language of

entrepreneurship, investment, and corporate development.

While this

framework may offer tangible benefits to certain segments of the arts

ecosystem, it aligns poorly with the realities of fine art, which constitutes

the majority of artistic practice. The non-market value of artistic work, the

uncertainty of long-term research and production, and the non-linear nature of

artistic achievement do not fit neatly into startup models.

As policy

frameworks increasingly center on corporatization, commercialization, and

scalability, the foundational domains of fine art become structurally

inexpressible. This approach is

superficial and short-sighted because when artistic value is defined only in

terms of what can be immediately disseminated, cultural policy inevitably

counts only the fruit while allowing the seeds to wither.

The foundations

of fine art are built not through programs, but through time—through the slow

interweaving of education, criticism, exhibition infrastructure, documentation,

research, archives, and museum systems. As this foundation weakens,

internationalization devolves from meaningful entry into global discourse into

mere momentary exposure.

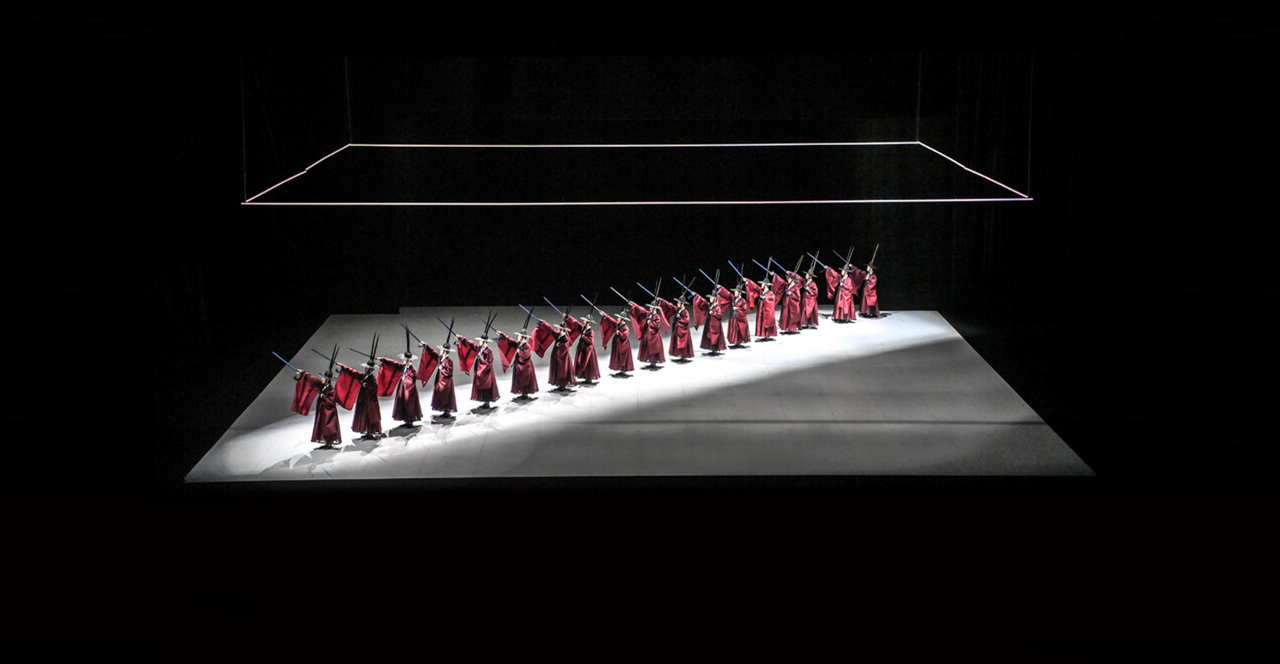

Art Korea Lab:

Reconsidering the Nature of Its Achievements

Art Korea Lab

provides perhaps the most emblematic example of this issue. Its reported

achievements for 2025 are, numerically speaking, clear: approximately 70,000

annual users, 150,000 cumulative visits, around 4 billion KRW in total

investment raised, the discovery of 47 convergence-art projects, and increased

utilization of facilities such as media walls, kinetic installations, and

immersive sound studios.

View of Art Korea Lab

However, upon

closer examination, these achievements align less with the internationalization

of Korean contemporary art than with the overseas expansion of

technology-driven creative content.

Art Korea Lab’s

stated mission encompasses education, experimentation, prototyping,

distribution, and startup incubation at the intersection of art and technology,

and its performance indicators are correspondingly aligned with investment,

employment, and global expansion.

Group photo of participants at “2025 Art Startup Day,” hosted by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and organized by the Arts Management Support Center / Source: Startup Daily

This is a

strategically understandable choice. Technology-based art offers high mobility

and scalability, enabling short-term international success. But when this

pathway is generalized as the internationalization of Korean contemporary art

as a whole, a serious problem arises. The internationalization of art is not a

matter of participation counts or technological scale, but of how works are

interpreted, recorded, and situated within international discourse, museums,

collections, and critical systems.

As structures

that prioritize “what has been implemented” over “what is being articulated”

become more entrenched, fine art is pushed ever further from the center of

policy.

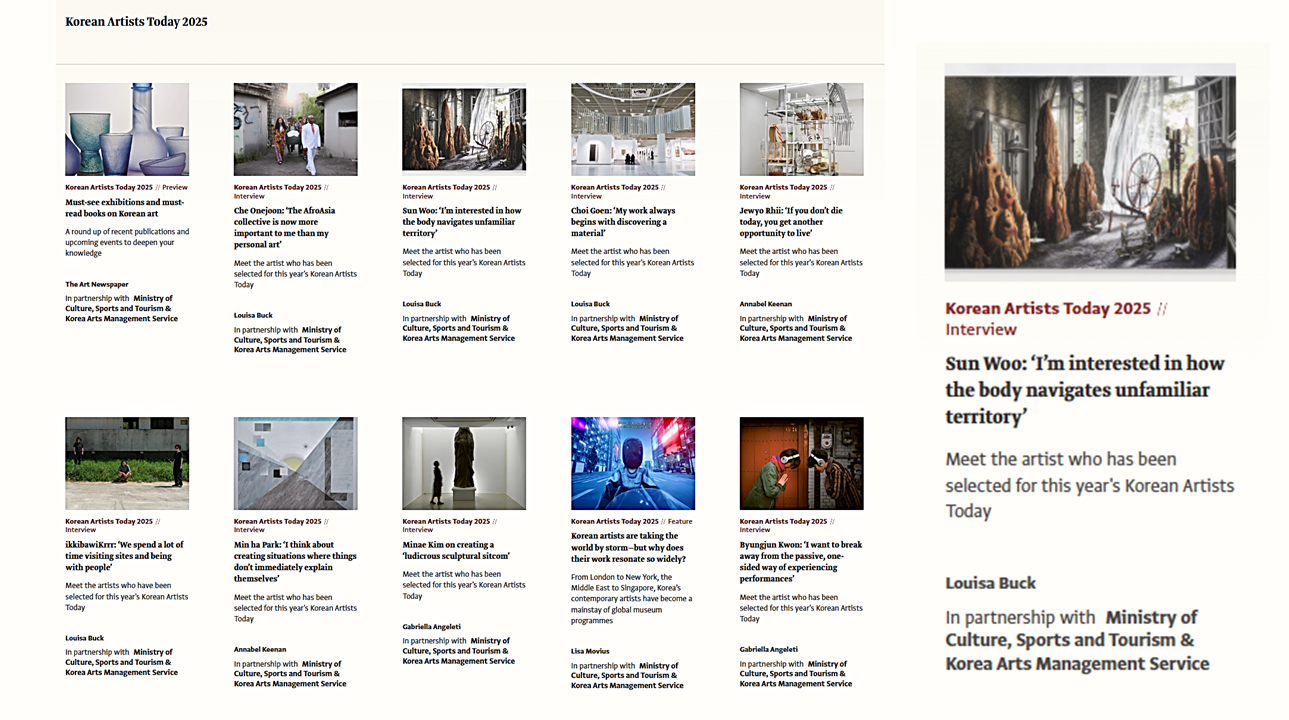

Internationalization

Is Not a Movement, but Contextualization

Internationalization in art

cannot be explained by the number of overseas exhibitions or technical

sophistication.

What matters is how a work is interpreted within global art

discourse,what art-historical position it occupies, and how it connects to museums,

collections, and systems of criticism.

Current

performance metrics emphasize questions of implementation and scalability,

rather than meaning and context. As a result, what travels abroad is often not

an aesthetic language but a technological format—closer to entry into

international media-arts markets than into the global art world.

This structure

disadvantages fine artists not because of a lack of capability, but because of

the way support systems are designed. Painting, sculpture, concept-driven

installation, and non-material practices are inherently difficult to visualize

within short-term, results-based evaluations.

What Should

Public Platforms Be Responsible For?

Serving as a

global distribution hub for technology-based art and bearing responsibility for

the internationalization of Korean contemporary art are fundamentally different

objectives. If both are to be pursued simultaneously, performance indicators

and support structures must be clearly differentiated.

When

heterogeneous outcomes are bundled under a single banner of “global success,”

technology-driven sectors are strengthened, while fine art is naturally

marginalized. This is not a matter of intention, but of structure.

Before

Results, the Criteria Must Be Rebuilt

For the President’s

remarks to carry genuine significance, they must lead not only to increased

funding, but to a redesign of support criteria themselves. Unless obsession

with short-term results is abandoned and parallel investment is made in

preserving seeds and roots—long-term working conditions for artists, criticism

and documentation, archives and museum systems, and sustained engagement with

international discourse—the internationalization of Korean contemporary art

will remain structurally unattainable.

The

internationalization of Korean contemporary art is not a question of adopting

more technology, but of deciding which art, and by what standards, is

introduced to the world. This is not a moment to celebrate results, but to ask

what those results have cost—and to reset direction accordingly.