Exhibiton View / © Colleen J. Dugan/National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution

Exhibiton View / © Colleen J. Dugan/National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution

Exhibiton View / © Colleen J. Dugan/National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution

A special

exhibition of Korean art,《Treasures of Korea:

Collected, Cherished, Shared》, is currently on view

at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C.

This exhibition

marks the first stop of an international tour based on the collection donated

by the late Lee Kun-hee. It is jointly organized and presented by the National

Museum of Korea and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

More than 200 works spanning from antiquity to the modern period are on

display, offering a broad survey of the historical trajectory of Korean art.

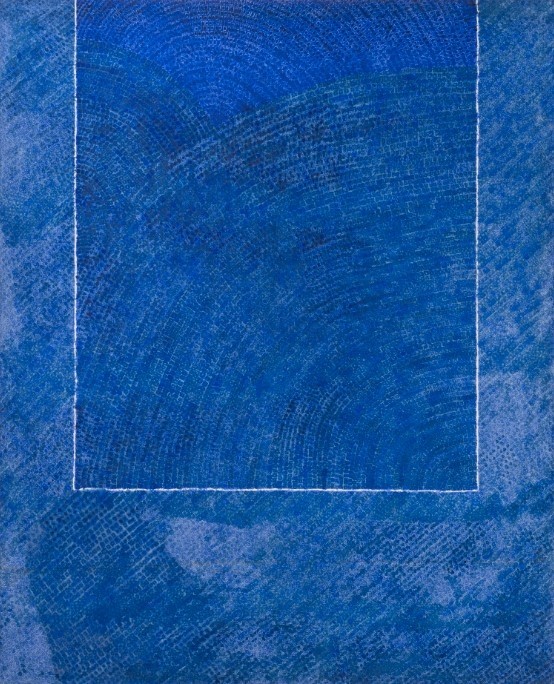

Kim Whanki, Echo of Mountains 19-II-73 #307, 1973. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Park Saeng-kwang, Shamanism 3, 1980. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

In its exhibition

materials, the National Museum of Asian Art describes the show as a large-scale

presentation that demonstrates the historical depth and breadth of Korean art.

It highlights as a key context the transition of a private collection into public

ownership, followed by close institutional collaboration that integrates

scholarship, conservation, and exhibition.

The materials

also note that Korean art has long been positioned within East Asian

collections dominated by Chinese and Japanese narratives in Western museums,

emphasizing that this exhibition introduces Korean art through an independent

and coherent narrative.

Artist unknown, Chaekgeori (Books and Scholar’s Objects), late 18th–19th century, Joseon dynasty, folding screen (chaekgado), color on paper, National Museum of Korea.

Chaekgeori (or chaekgado) paintings depict books, writing implements, and various objects arranged in a still-life format. They symbolize learning, cultivation, prosperity, and auspiciousness, and represent a major genre of late Joseon court and literati painting.

“The

Washington Post” described the exhibition as the

largest presentation of Korean art ever held at the National Museum of Asian

Art. The newspaper noted the curatorial decision not to separate premodern and

modern works, instead arranging them in a continuous sequence that reveals the

long-term flow and aesthetic continuity of Korean art. While acknowledging

heightened global interest in Korean culture driven by popular media, the

article emphasized that the exhibition remains firmly grounded in

art-historical context.

The Beopgodae (Drum Stand), one of the most popular works in the exhibition. Courtesy of the National Museum of Asian Art.

The Beopgodae is a Buddhist ritual object from the Joseon period, used to support the beopgo (ritual drum) in temple ceremonies. Sculpted in the form of an imaginary animal, it embodies both ritual function and sculptural sophistication.

Beopgo (Buddhist ritual drum).

“Forbes” approached the exhibition as an interpretive presentation designed

to facilitate understanding of Korea’s artistic heritage. Rather than focusing

on scale or spectacle, the article highlighted the chronological structure and

explanatory framework that allow visitors to follow the development of Korean

art with relative clarity. It also emphasized that the Lee Kun-hee Collection

functions not as a reflection of personal taste, but as a resource for public

education and scholarly research.

The Asian art

periodical “Asian Art Newspaper” introduced the exhibition as one of the

Smithsonian’s major initiatives, summarizing its scope through key facts: more

than 200 works on display, the inclusion of nationally designated cultural

treasures, and joint organization by Korea’s national institutions. Its

coverage focused on the institutional aspects of donation, collection, and

overseas exhibition rather than interpretive analysis.

The exhibition’s

subtitle—‘Collected’, ‘Cherished’, ‘Shared’—frames its central

narrative: the transformation of a private collection into national holdings

and, ultimately, into an international public exhibition. Official materials

explain that this progression structures the entire exhibition, foregrounding

not only the artworks themselves but also the contexts of collecting and public

sharing.

The exhibition

brings together premodern works from the National Museum of Korea and modern

and contemporary works from the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art,

Korea. Masterpieces such as Jeong Seon’s Inwangjesaekdo (Mount

Inwang after Rain), Kim Hong-do’s Chuseongbudo

(Illustration of the Rhapsody on Autumn Sounds), along with court

paintings and white porcelain, represent the aesthetic foundations of the

Joseon dynasty. The modern section includes works by Park Su-geun, Kim Whanki,

and Kim Byeong-gi, highlighting emotional and formal continuities with earlier

traditions.

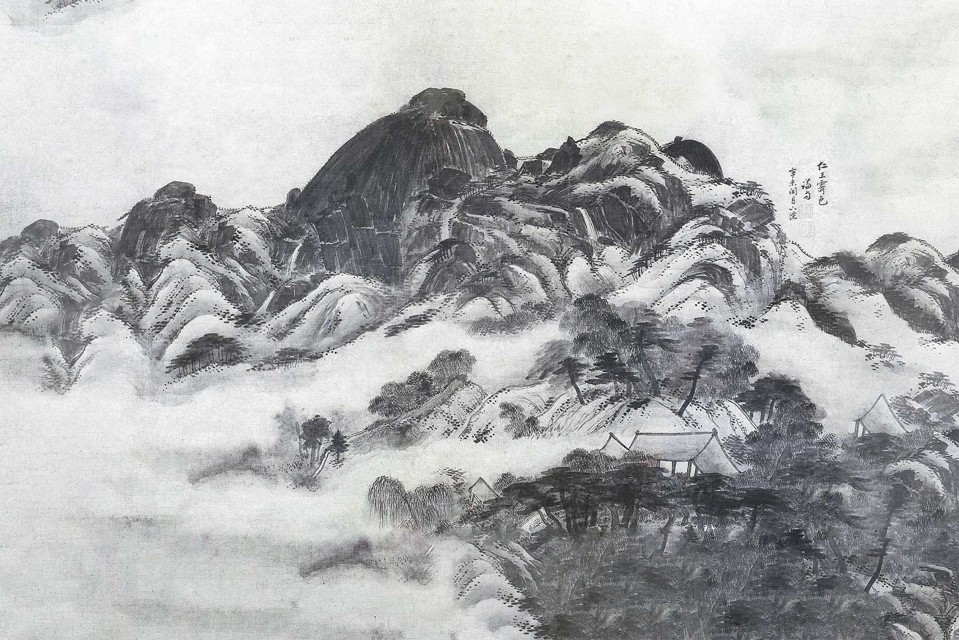

Jeong Seon, Inwangjesaekdo (Mount Inwang after Rain), 1751, Joseon dynasty, ink on paper, National Museum of Korea.

Jeong Seon’s Inwangjesaekdo

is a landmark of late Joseon “true-view” landscape painting. Depicting Mount

Inwang just after rainfall, the work captures the scene with powerful brushwork

and close observation. Rather than following idealized Chinese landscape

conventions, it is based on direct study of an actual site, a defining

characteristic of true-view painting.

Through layered

ink tones and vigorous strokes, the rocky mountain surfaces convey the texture

and vitality of nature, while the fleeting change in weather lends the

composition a sense of tension and immediacy. The painting is widely regarded

as a key example of how Joseon artists established an independent landscape

tradition grounded in lived experience.

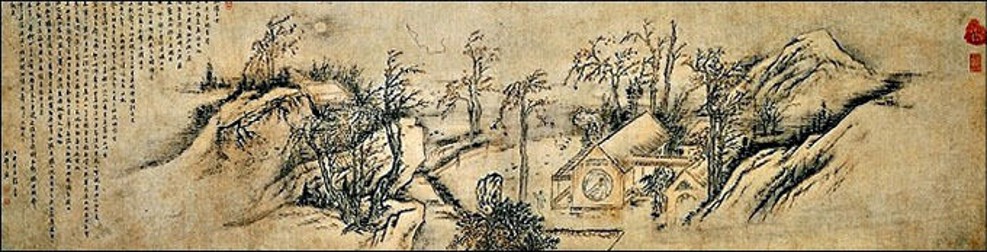

김홍도(金弘道),〈추성부도(秋聲賦圖, Illustration of the Rhapsody on Autumn Sounds)〉, 조선 18세기 말, 종이에 수묵담채. 국립중앙박물관 소장.

Chuseongbudo visualizes the “Rhapsody on Autumn Sounds” by the Song-dynasty

scholar Ouyang Xiu. A literati-style landscape, it conveys quiet reflection and

contemplative emotion inspired by seasonal change. In contrast to Kim Hong-do’s

well-known genre scenes, this work is marked by restrained brushwork, balanced

composition, and a strong literary sensibility, exemplifying the fusion of

literature and painting in late Joseon literati art.

International

media and official sources alike frame the exhibition as a case that

illuminates not only the artistic quality of Korean art, but also the process

by which a donated private collection becomes part of national holdings and is

presented within an international museum context. While the global spread of

K-pop and Korean cinema is often cited as background, the exhibition itself is

consistently described as a project centered on scholarly and institutional

frameworks.

After closing in

Washington on February 1 this year, the touring exhibition will travel to the

Art Institute of Chicago (March 7–July 5, 2026) and then to the British Museum

(September 10, 2026–January 10, 2027).

References

- Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art – Exhibition Overview

- Smithsonian Newsdesk – Press Release

- Smithsonian NMAA – Accessible Exhibition Text

- The Washington Post – Korean Treasures at the Smithsonian

- Forbes – Korean Treasures Offers Insight Into a Rich Artistic Heritage

- Asian

Art Newspaper – Korean Treasures: The Samsung Family

Collection

- The Korea Society – Curatorial Roundtable