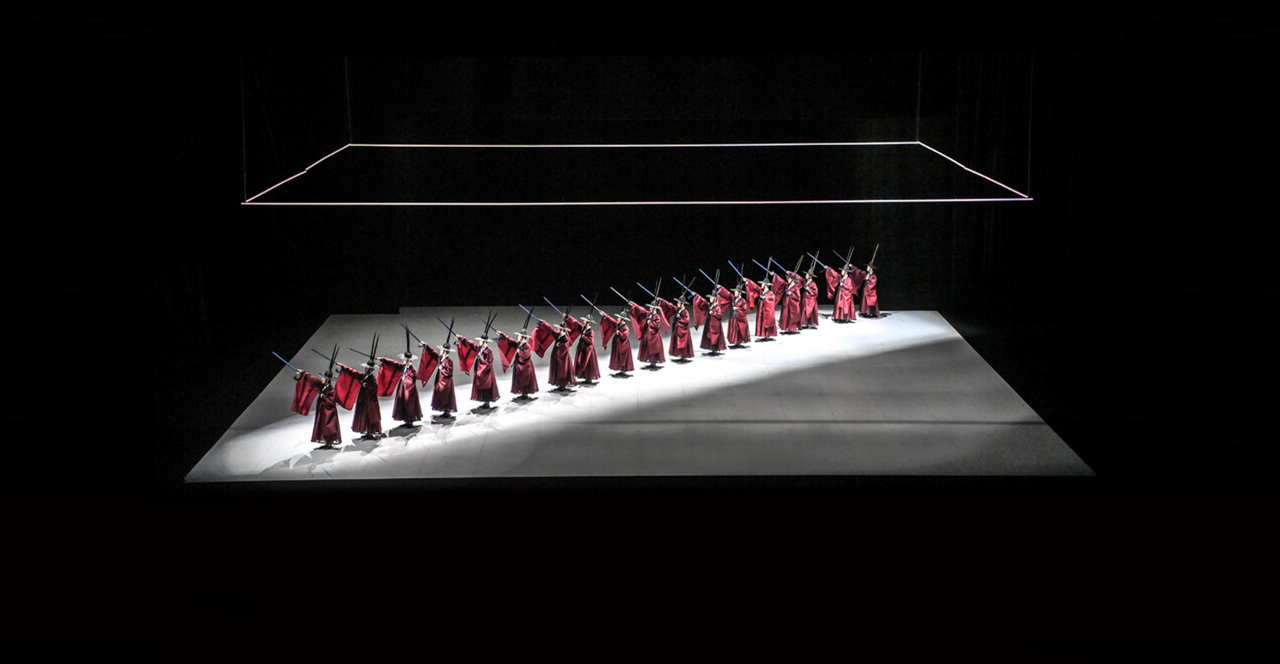

At DDP Museum

Exhibition Hall 1, a large-scale retrospective of《JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: Signs:

Connecting Past and Future》, is currently on view.

Representatives

of the Basquiat estate participated in shaping the exhibition’s direction, and

the co-curatorial team—Jiyoon Lee (Founder of SUUM PROJECT; Artistic Director

and Curator), alongside the internationally recognized Basquiat specialists

Dieter Buchhart and Anna Karina Hofbauer—designed its structure and narrative

together. The presentation brings to Seoul roughly 230 items in total,

including major paintings reportedly insured at around KRW 1.4 trillion, some

70 paintings and drawings, and approximately 160 pages of archival material

excerpted from eight notebooks.

Its scale and

numbers drew attention even before opening, but what the exhibition ultimately

puts on the table is not a matter of magnitude. It asks viewers not simply what

to see, but how to read. And that “reading” begins with the surface itself—with

the marks left behind and the rhythm of what has been worked over.

‘New York, New York’, signed SAMO© and dated New York 1981 on the reverse. Acrylic, oil stick, spray paint, silver spray paint and paper collage on canvas, 128.4 x 226.2 cm. 50 1/2 x 89 in. Private Collection. Photo: Aproject Company

When you stand before the work, what registers first is not

polish but roughness that feels deliberately retained. In place of refined

brushwork or a stable composition, the canvas is governed by repetition and

friction—by traces of erasure. Smeared oilstick, lines that seem scratched into

being, and words and symbols returned to with insistence crowd the pictorial

space.

The surface reads less as impulsive release than as a

calculated attempt to translate the noise, tension, and imbalance of 1980s New

York into painterly terms. Basquiat’s canvas is not so much an outpouring of

feeling as a weave in which disparate signs collide and overlap.

The exhibition begins precisely here, with a question that is

both historical and formal: why would an artist in the 1980s choose, instead of

a “beautiful image,” to leave jagged, incomplete text and symbols on a canvas?

1. Historical

Context: Why Did “Language” Enter the Canvas?

New York in the 1980s—the city in which Basquiat worked—stood

at a significant cultural and intellectual turning point. If the previous

generation of Abstract Expressionism emphasized the materiality of paint,

physical gesture, and the artist’s interior life while keeping literary

elements at a distance, Basquiat’s generation moved with a different set of

pressures. In this period, text and sign increasingly functioned as key

instruments for understanding the world.

In the humanities, semiotics, structuralism, and

deconstruction—associated most visibly with Roland Barthes and Jacques

Derrida—shifted attention from what an image represents to how meaning is

produced. Meaning was understood not as fixed but as unstable, sliding, and

continually open to re-reading, and that sensibility seeped into visual culture

at large.

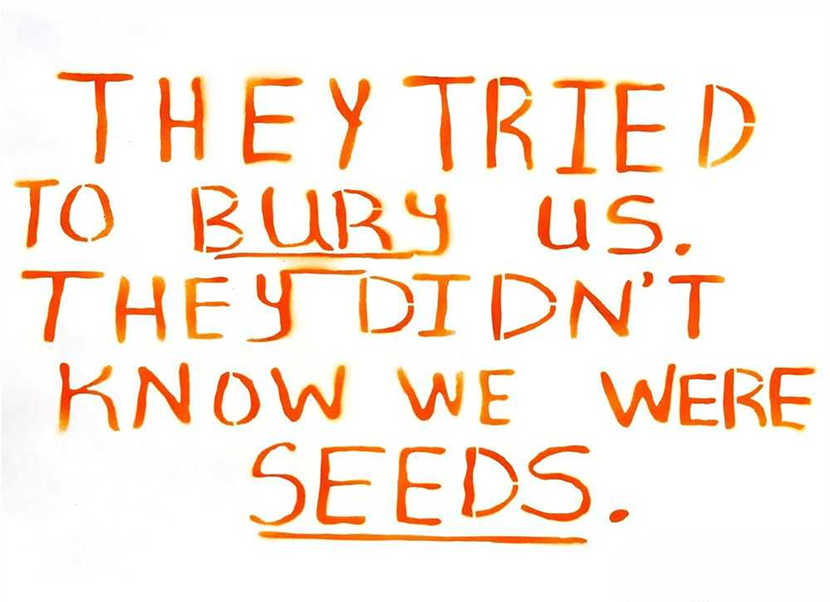

This theoretical turn

did not remain inside academia. Hip-hop culture and graffiti, formed in the

Bronx in the 1970s, pulled words and sentences onto the street’s surface,

making text physical and visible. A sentence became something read and seen at

once; tags, scrawls, and rhythm fused with the city’s pulse to form a visual

vernacular. Whether or not Basquiat systematically studied theory, the New York

he inhabited was already an environment acutely responsive to text and symbols.

Destroyed and abandoned buildings along Hoe Ave. and the IRT line in the Bronx, 1981. Photo: Henry Chalfant. Courtesy: Eric Firestone Gallery, New York.

“KEL CRASH” by Kel and Crash, on the 7th Avenue Express, 1980. Photo: Henry Chalfant. Courtesy: The Bronx Museum.

Parallel currents were already unfolding within art.

Conceptual practices in the 1960s and 70s shifted attention away from the craft

of making and toward the conditions under which meaning takes shape. Joseph

Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965) demonstrated how an object,

an image, and a definition operate on different planes, making clear that

visual art could no longer be confined to form alone. Lawrence Weiner likewise

presented the sentence itself as the work, asserting that language can hold

sculptural force.

(Left) Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965 © 2025 Joseph Kosuth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York (Right) Lawrence Weiner, Apropos Lawrence Weiner exhibition installation view, 2022 © Marian Goodman Gallery (Bottom) Cy Twombly, The Italians, Rome, January 1961 © 2025 Cy Twombly Foundation

Meanwhile, Cy Twombly had, since the 1950s and 60s, drawn

scribble, handwriting, and fragmentary phrases into painting, blurring the line

between writing and drawing. In his work, language functions—before it delivers

meaning—as trace and rhythm. These trajectories helped form the aesthetic

ground from which Basquiat could later emerge.

Ultimately, the entry of language into Basquiat’s canvas was

not accidental; it was the result of an era in which the border between ‘seeing’ and ‘reading’ was dissolving—an intersection of historical conditions,

street culture, and the legacy of conceptual art. His painting was what emerged

when those currents met.

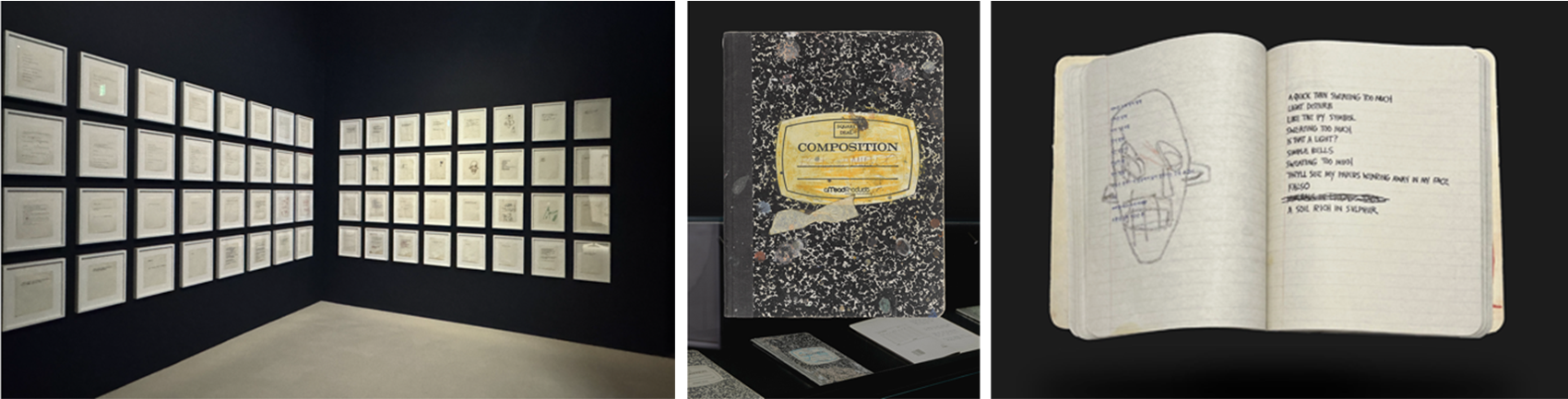

2. Notebooks: Crushed Oilstick and Edited

Information

A key component of this show is the set of eight notebooks—roughly 160

pages of documents—presented here as essential material for understanding

Basquiat’s point of departure. These notebooks are not simply a bundle of

doodles; they resemble a private archive built through repeated collecting,

arranging, and accumulating of words, names, sentences, and signs. They reveal

him not as an artist who produced images purely on emotional impulse, but as

someone with an editor’s mind—gathering, sorting, and cutting information as

part of his preparation.

Exhibition View of《JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: Signs: Connectiong Past and Future》, 2025, Photo: Aproject Company & Notebook image @ SUUM project

The pages repeatedly surface biblical quotations, anatomical

terms, Black historical figures, the names of athletes and musicians, lists of

words, and shards of sentences. These elements reappear later in paintings and

drawings, rearranged in new contexts. The notebooks function not merely as memo

pads but as reservoirs of language—workspaces where words are stored, tested,

and kept in motion before they migrate into painting.

That layered record becomes material trace on the canvas. The

crushed oilstick marks and overpainted letters visible in the large works on

view are the result of notebook language translated into painterly action.

Basquiat wrote words, struck through them, and covered them again—over and

over.

As his remark suggests—“I cross out words so you will see

them more”—this erasure is not deletion but insistence. Scratches and remnants

seize the gaze and keep meaning suspended, refusing final settlement. In that

process, painting becomes less a vehicle for delivering a message than a place

where text and image are generated, interrupted, and forced into collision.

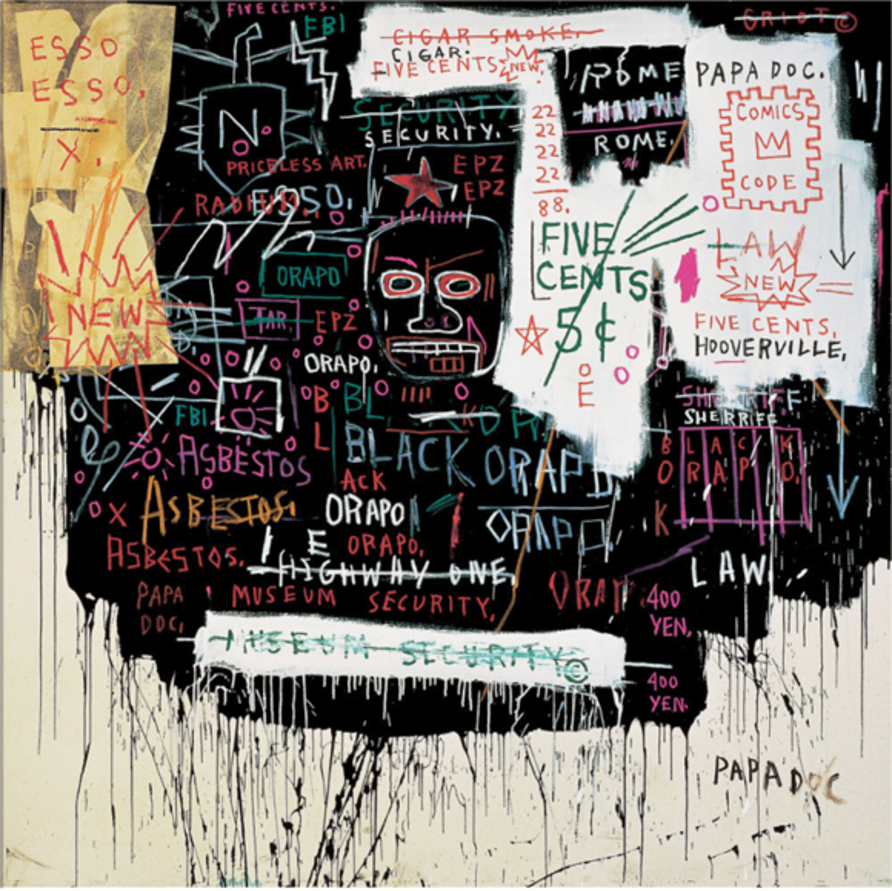

3. Colliding Symbols: Dissecting

Institutions and Capital

Included in

the exhibition, Museum Security (Broadway Meltdown) condenses the way text and symbols

can operate as social critique. The repeated phrase “Museum Security” exceeds a

job title; it points to the constrained position Black people were often

allowed to occupy within the American art institution of the 1980s.

Museum Security (Broadway Meltdown), Acrylic, oil stick and paper collage on canvas, 84 x 84 in. (213.4 x 213.4 cm.), Painted in 1983 (14), Private Collection.

The downtown

art world centered around SoHo was governed by entrenched white power

structures, and Black individuals were frequently recognized not as artists but

as guards or service workers. Basquiat became an exceptional success, yet he

was also consumed through the romantic image of a “street genius,” turned into

a spectacle. He faced suspicion even at openings, and could become a target of

surveillance in the very spaces where his work hung.

Phrases such

as “Esso” and “Priceless Art” register a cold awareness of how art circulates

under the logic of capital. The crown—repeated throughout his work—is less a

boast than a symbolic sovereignty claimed by one who has been excluded. By

placing the crown beside commodity signs, Basquiat compresses into a single

image the contradictions knotted between art, power, and money.

4. Gathering the Fragments: The

Aesthetics of a Collection

Another point that sets this retrospective apart is “the diversity of its sources”. Rather

than relying on the holdings of a single museum, it brings together works from

private collections around the world, revealing multiple faces of Basquiat that

resist being organized into one stable account. Works collected across

different contexts and tastes meet in the space of DDP, making evident—without

forcing the point—that his practice cannot be reduced to a single style or

narrative.

This configuration encourages viewers to approach him not as

a fixed figure within a particular lineage, but through a wider lens: the ways

signs and language operate visually.

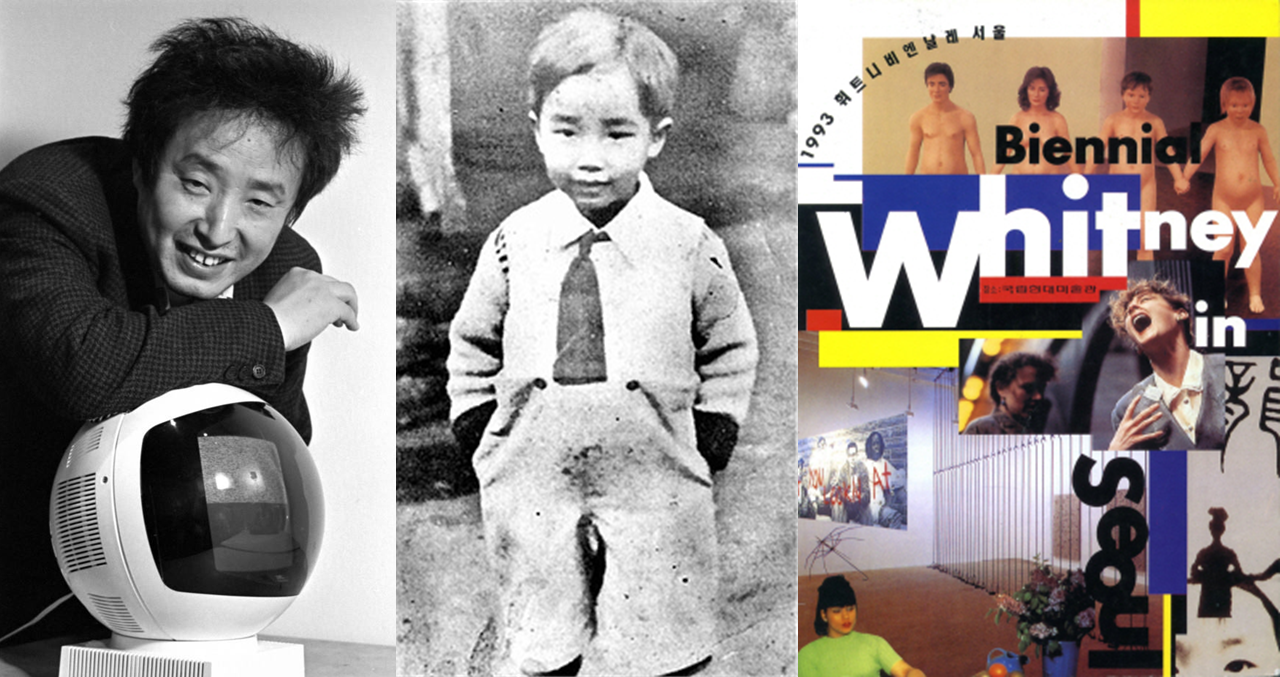

Notably, the exhibition places Basquiat’s works in limited

proximity to the Hunminjeongeum Haerye (the explanatory text for the Korean

alphabet), rubbings of the Bangudae Petroglyphs in Ulsan, and Nam June Paik’s

TV-robot works. Rather than drawing lines of influence, this functions more as

a prompt to recognize, side by side, how letters, symbols, and technology have

acted as visual language across different eras and media. The visitor is not

compelled to decode; instead, the display gently widens attention to the many

ways signs have shaped human thought and expression.

Closing:

Questioning the Signs of Our Time

Basquiat’s status is not

the kind that neatly overlays popular symbolism and art-historical achievement

at equal weight. His work sharply captured the sensibility of its image

culture, leaving a powerful imprint through the fusion of text and image. Yet today,

the evaluation surrounding his name is often shaped in advance by the language

of the market and the stories of circulation, before sustained looking has a

chance to arrive.

Price,

scarcity, a mythologized biography, and endlessly repeated images can operate

like a ready-made framework, producing a symbolic excess that outgrows the

work’s actual achievement. At that point, Basquiat functions less as an artist

than as an icon consumed by contemporary culture.

This

does not mean his work is light or superficial. Rather, the role he played in

art history is less a singular “turning point” that single-handedly produced a

rupture than a concentrated instance in which already-formed

currents—conceptual art, text-based practice, graffiti culture, and the

circulation of mass imagery—crossed and intensified. Put differently, he did

not invent an entirely new language; he made unusually visible, with

exceptional clarity, the clash of visual and cultural languages already

scattered across his time.

For

this reason, responses to Basquiat often come with built-in tension. Popular

fascination, institutional endorsement, and speculative fever can make the work

feel “already known,” leaving it vulnerable to consumption without critical

distance. Seen this way, Basquiat is less a “great exception” than a case that

condenses the conditions under which late twentieth-century image culture

operated.

Within

such conditions of consumption and circulation, just as Basquiat built an

identity in 1980s New York through his own system of signs, we, too, need to

look back at the symbols and markers in which we live. When we recall that his

work was not simply personal expression but the result of a continuous

awareness of his position within the era’s structures of language, power, and

images, the question becomes not a passing impression but a stance.

What

is “the crown” for us now, and what is the “copyright (©)” that invisibly

defines—or controls—us? The landscape of today, where social media metrics,

algorithms, and the logic of capital set the terms of what feels legible and

desirable, resembles—strikingly—the cultural conditions Basquiat faced in the

1980s. Only now, signs circulate faster, grow more intricate, and harden into

the measures by which perception and judgment are calibrated.

Therefore, in this exhibition, rather than consuming Basquiat through the myth built around his image, we should attend closely to his way of working—the fierce discipline of speaking, striking through, erasing, repeating, and testing meaning. His paintings do not deliver a sealed statement; they show, plainly, how image and language clash, slip, and generate sense in motion. The encounter, then, is not a backward-looking retrospective so much as a question that still presses on the present.

Just as Basquiat fought the given order on the canvas, we are led to ask how the marks of algorithms and capital—encountered daily—shape the contours of our thinking. In the end, Basquiat’s traces can prompt each of us, from where we stand, to refine how we read such marks—and to consider how we might write them anew.

Exhibition Information

Exhibition: JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: Signs: Connecting

Past and Future

Venue: DDP (Dongdaemun Design Plaza), Museum

Exhibition Hall 1

Dates: 2025.09.23 – 2026.01.31

Kim Heejo is an artist working across painting and sculpture, approaching form as a *schematic medium* grounded in systems-based thinking. Shaped by long-term practice in New York and ongoing work in Seoul, her work emphasizes structural logics and generative processes over fixed imagery. In this article, she presents an artist-led reading of a Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition.

www.heejokim.com

| @in.station