Why

does the Korean art world depend on external discourse?

In

Korean contemporary art, the dominance of external theories is not simply a

matter of imitation or personal preference. It results from a long-accumulated

structure shaped by art education, institutional frameworks, and evaluation

systems within the art market and public institutions.

Concepts

such as postcolonialism, diaspora theory, Western gender theory,

intersectionality, and identity politics are widely used not because Korean

artists favor them individually, but because the system itself makes it

structurally difficult to construct one’s own language. To understand this

phenomenon, we must examine how the Korean art world has produced a vacuum in

which external discourse fills the gaps that the system itself created.

The

educational structure and the emergence of a linguistic void

Korean

art schools have long maintained a studio-centered curriculum. Theory courses,

when offered, often rely on translated texts from the 1980s–1990s or general

surveys of Western modern and contemporary art.

Meanwhile,

contemporary global art—post-material installations, post-internet practices,

AI-based creation, archive-centered works, posthuman discourse, and newly

emerging non-Western art geographies—appears minimally, if at all, in actual

instruction.

Postcolonial

or diaspora theories, once central to Western academia, are still taught in

Korea largely through outdated translations, even though global art discourse

today has shifted toward far more diverse and multi-layered perspectives.

In

this educational vacuum, students graduate without the ability to articulate

their own experiences in a contemporary artistic language. As a result, they

naturally gravitate toward pre-existing external concepts as the easiest tools

for explaining their work.

The

institutionalization of overseas study and the “re-importation” of discourse

Studying

abroad offers artists valuable exposure, but as generations of overseas-trained

artists have occupied key positions—professors, curators, museum staff—the

Western theories they learned abroad have become institutional standards in

Korea.

Consequently,

concepts such as poststructuralism, Foucauldian power/knowledge, postcolonial

theory, Judith Butler’s gender performativity, Donna Haraway’s posthumanism, or

Deleuze & Guattari’s rhizome were adopted not through a process of

re-contextualization, but as ready-made answers.

With

limited training in reconstructing these ideas through Korean social reality,

external theories became “concepts to import,” and many artists perceived them

as the safest and most institutionally advantageous choice. External discourse

thus turned from an option into an institutional habit.

How

competitions, residencies, and institutional evaluations reinforce this

linguistic structure

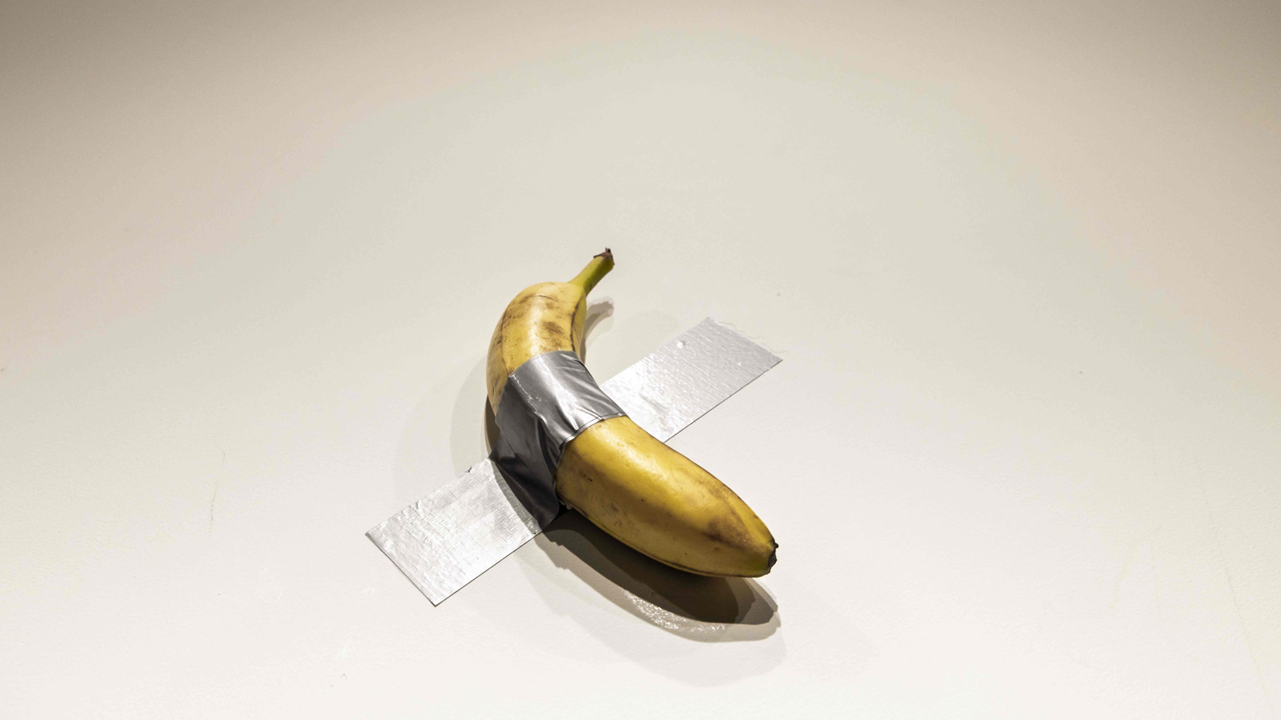

In

Korea, the texts required for entry into the art system—portfolios, residency

applications, competition statements—often prioritize “global language

standards” over the substance of the artwork.

Words

like “boundary”, “identity”, “memory”, “trauma”, “otherness”,

“migration”, and “gender politics”—terms borrowed from

postcolonial, feminist, or identity-based theories—are frequently used

regardless of whether they genuinely emerge from the artist’s lived context.

What matters is the impression of conceptual completeness rather than

conceptual relevance.

The

issue is that these terms function as conceptual templates rather than

questions rooted in Korean reality. The work becomes not a site for generating

inquiry but a case study to confirm an imported theory. The artist’s experience

is reduced to supporting material.

Global

art’s rapid shifts and the disconnect within Korean art education

Contemporary

global art is evolving rapidly.

Ecological transitions, technology and AI, bio-art, posthumanism, expanded

regional perspectives, postcolonial-after neoliberal critique, and Global South

discourse are already central topics in major institutions.

Yet

Korean art schools remain largely disconnected from these developments.

Case studies of contemporary artists, analyses of new institutional models, and

the expansion of non-Western perspectives rarely appear in curricula or

teaching materials.

Students

graduate without an understanding of contemporary global standards. The

repetition of external theories thus becomes an inevitable response

produced by a lack of access to current information.

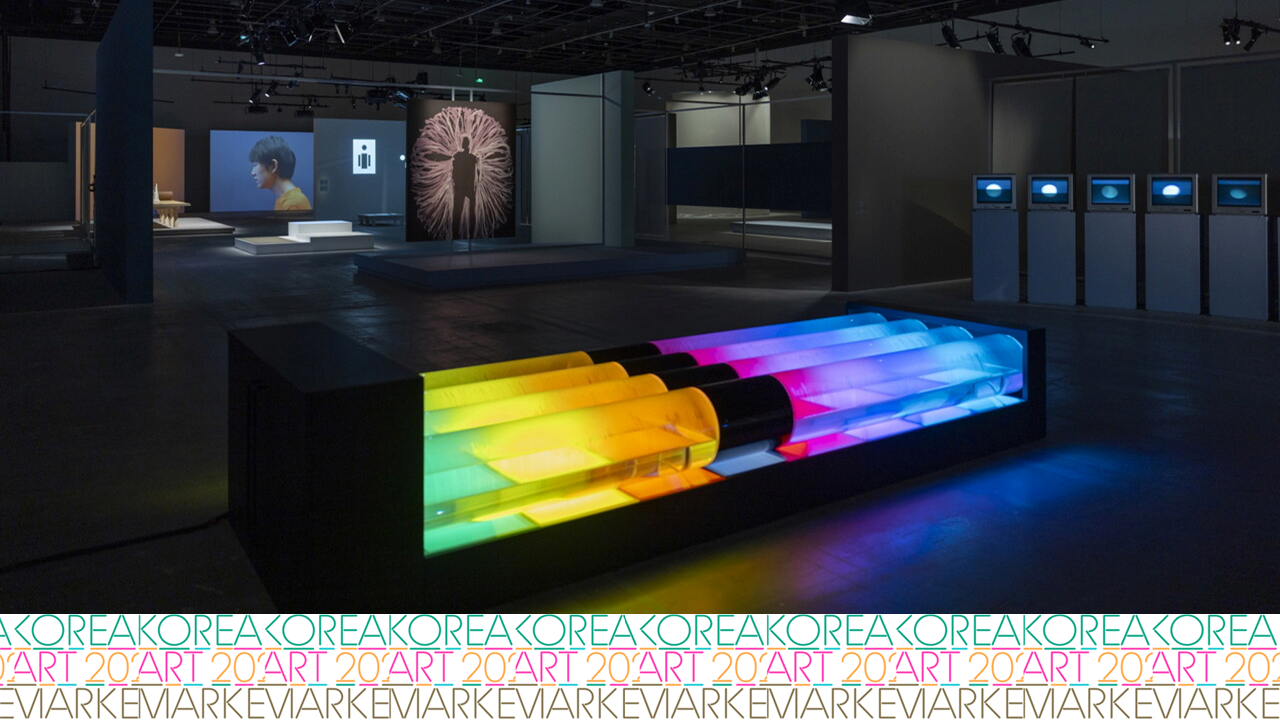

How

four artists exemplify a mode of reconstruction—not imitation

Kimsooja,

Do Ho Suh, Lee Bul, and Haegue Yang did not simply apply external discourse.

Their practices begin with Korean lived realities, and from that starting

point, new relationships with external theory organically emerge.

Kimsooja’s

work stems from lived experiences of Korean womanhood, labor, family, and

mobility—translated through bodily action, sewing, and textile

materiality—before intersecting with discussions of migration or gender.

Do

Ho Suh begins not with identity theory, but with deeply Korean spatial

structures—semi-basement apartments, narrow alleys, multi-unit homes—and

transforms them architecturally and sculpturally into questions of place and

subjectivity.

Lee

Bul’s early works confront bodily discipline, social control, and patriarchal

violence specific to Korean society. The work’s connection to global gender or

body politics came later, as a result of these investigations rather than as a

theoretical starting point.

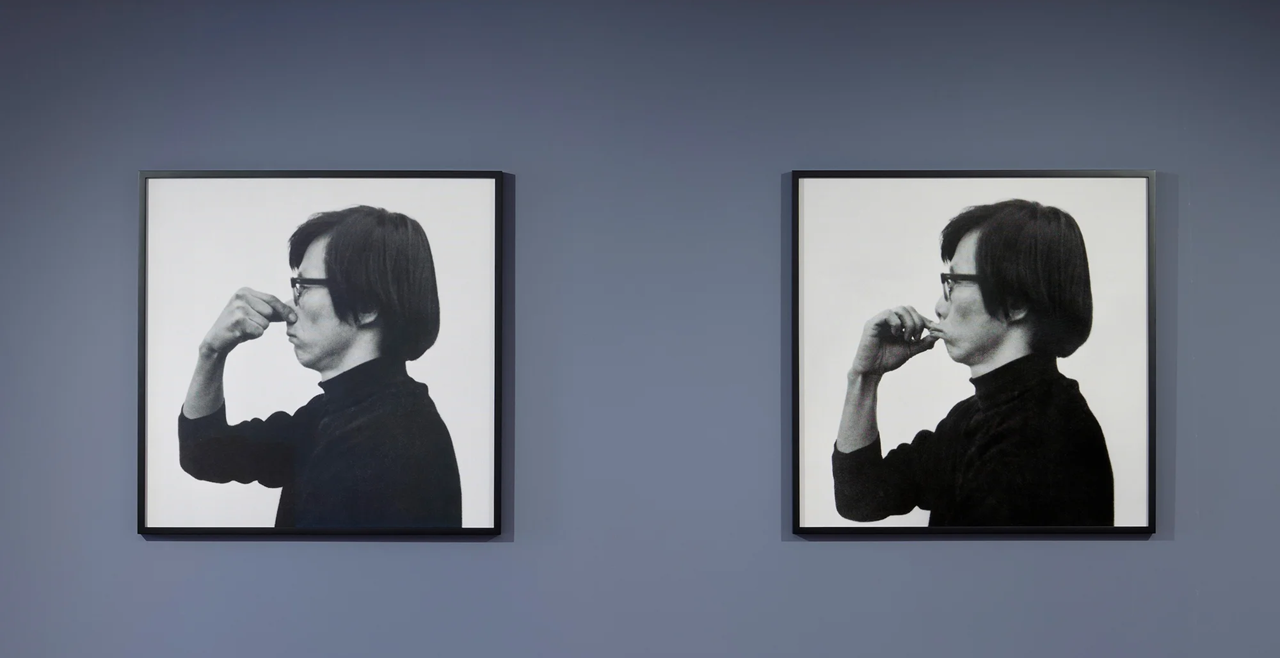

Haegue

Yang transforms domestic Korean objects, textures of labor, and folk materials

into sensory systems before those structures intersect with global discourses

on mobility or “in-betweenness.”

For

all four, external theories were not ‘explanatory tools’ but emergent

points of contact produced by their own experience-based languages.

Toward

a future direction for Korean art

To

move beyond the repetition of external discourse, Korean contemporary art does

not need more imported theory. It needs the ability to construct

questions from its own reality and to organize those questions into

visual and conceptual form.

Korea’s

lived terrain—division and compressed growth, family structures, urban speed,

religion and regionality, class imbalances, and technological shifts—is not

merely a set of themes but a vital sensory and conceptual foundation for art.

Through

sustained interpretation, comparison, and reconstruction of this reality,

Korean art can shift from being a consumer of external ideas to a producer of

new discourse.

This

requires updates in art education, greater productivity in Korean criticism and

curation, and evaluation systems that prioritize experiential grounding over

theoretical fluency. Structural change will take time, but accumulated in the

right direction, it can finally open a space where Korean contemporary art

builds its own linguistic horizon rather than operating in the shadow of

external theories.