This text

is not written to introduce or defend Korean contemporary art. Nor is it

intended to declare a new movement or to predict future artistic forms. The point

of departure for this series is a more fundamental question:

Under what

conditions has contemporary art operated,

and are

those conditions still valid today?

Today, the

term “post-contemporary” is more often invoked as a convenient

label for an indeterminate state following contemporary art than as a

concept grounded in theoretical consensus or a coherent analytical framework. It

frequently functions as a provisional marker—used to gesture toward new tendencies,

generations, or changes that have yet to be clearly defined—rather than as a concept capable of

explaining concrete conditions of operation or criteria of judgment.

As a

result, “post-contemporary” tends to circulate either as a vague

signifier of the future or as yet another stylistic category, without leading

to a sustained analysis of how the foundational assumptions of contemporary art

have actually been transformed. For this

reason, this series does not begin by declaring or defining the

post-contemporary. Instead, it begins by examining what kinds of

outcomes the underlying conditions of contemporary art have in fact produced.

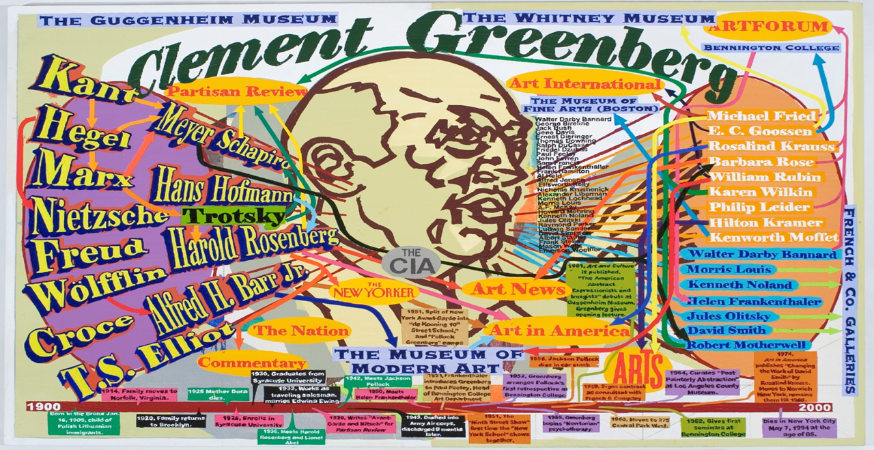

Contemporary

Art as a Cognitive System

Contemporary

art has never simply meant “art

produced in the present.” It

functioned as a cognitive system and as an institutional consensus. It was

grounded in the shared assumption that the world is interpretable, that

critique is effective, and that meaning can be continuously produced. Within

this framework, the artwork remained a central unit of analysis.

Criticism

and institutions operated as mechanisms that adjusted and accumulated meaning,

while judgments of value were understood not as fixed conclusions but as open

processes accessible to multiple interpretations. This system

was sustained by three core operative principles: the suspension of

judgment, relationality, and institutional critique. The ‘suspension of judgment’ served as a safeguard against the

violence of hierarchical evaluation based on a single criterion.

‘Relationality’ functioned

as an analytical framework for reading artworks within social, institutional,

and discursive contexts. Institutional critique aimed to expose and render

modifiable the power structures and norms embedded in art institutions. For a

time, these principles constituted some of the most effective aesthetic and

critical tools for interpreting the world.

From the

Suspension of Judgment to Structural Evasion

Over time,

however, these principles began to produce consequences that were not

originally intended. Here, the

suspension of judgment does not simply refer to a postponement of evaluation.

It describes a condition in which exhibitions and artworks refrain from

explicitly articulating what their objectives were, whether those objectives

were achieved, and what constituted failure.

In

this sense, the suspension of judgment no longer operates as a flexible

strategy but has hardened into a structural deferral of value judgment. Within this

structure, exhibitions continue to proliferate, yet the extent to which their

stated agendas are tested through selection, exhibition design, and audience

experience fails to accumulate as evaluative knowledge.

Failures are not analyzed, limitations are not corrected,

and judgments do not persist as criteria for subsequent exhibitions.

What once functioned as an openness to interpretation has thus transformed

into a mechanism that prevents judgment and responsibility from taking place at all.

Relationality

and the Eclipse of the Artwork’s Intrinsic

Value

‘Relationality’, too, has

undergone a significant distortion. Originally

conceived as a means of analyzing artworks within their social and

institutional contexts, relationality gradually shifted its function within

exhibition practices that repeated the same formats over time. Rather

than serving as a tool for critical evaluation, relational discourse

increasingly became a neutral language of explanation and justification.

The mere

presence of relations, participation, or contextual references began to stand

in for the artwork’s own

achievements. As a result, discussions of completion, form, density, structure,

and skill—core

components of artistic evaluation—were

displaced from the center of criticism, replaced by concerns that were

increasingly peripheral to the work itself.

The artwork ceased to function as an object of evaluation

and instead became a case, an event trigger, or a vehicle for activating discourse.

While relational networks expanded, the language capable of

analyzing and judging the artwork itself steadily weakened.

The

Institutionalization of Critique and the Erasure of Responsibility

Institutional

critique has likewise undergone a decisive shift. Initially,

it functioned as an aesthetic practice capable of exposing and challenging the

power structures of museums, biennials, markets, and discursive systems. Yet as

institutional critique became a standardized component of exhibitions, it

gradually stabilized into a predictable role performed within the authority of

the very institutions it once sought to unsettle.

In this

condition, critique continues to legitimize exhibitions rhetorically, but

it rarely reaches the point at which institutional responsibilities,

decision-making structures, or evaluative criteria are meaningfully altered. Questions

of who is responsible for curatorial decisions, on what grounds selections were

made, and why certain judgments succeeded or failed remain largely

unarticulated.

Critique is

repeated within institutional frameworks,

while

responsibility is diffused, minimized, or rendered invisible.

Reconsidering “Already

Legitimated Rules”

For a long

time, contemporary art has operated on an implicit assumption: that

exhibitions take place within already validated institutions, and that the

rules governing those institutions have secured sufficient legitimacy to be

trusted and followed by participants and audiences alike.

It is

precisely this assumption that now requires fundamental reconsideration. As long as

the rules, formats, and evaluative procedures of exhibitions are presumed to be

inherently legitimate, the actual outcomes they produce—and the

failures they generate—remain

largely unquestioned.

The problem

is not the existence of rules per se, but the lack of sustained inquiry into

whether those rules remain effective, what consequences they generate, and

whether they are open to revision.

The

Conditions of the Post-Contemporary

This

constellation—where judgment

is structurally deferred, relationality functions as justification,

institutional critique becomes institutionalized, and circuits of

responsibility and revision fail to operate—is what

this text refers to as the conditions of the post-contemporary.

These

conditions do not describe a future stage yet to arrive. They name a

structural situation that is already in operation but insufficiently recognized.

Nor is this condition limited to specific regions or non-Western contexts; it

characterizes contemporary art on a global scale.

The

Position of Korean Contemporary Art

Korean

contemporary art is among the fields that have experienced these conditions in

a particularly condensed form. Having rapidly internalized international languages and institutional formats, Korean art is no longer situated primarily as a respondent to Western discourse.

The question must therefore be inverted:

Who is now

capable of articulating these conditions with the greatest precision?

This shift

in perspective does not arise from a sense of lack, but from the necessity of

repositioning toward the future. Only those who have passed through these

conditions can reflect upon them critically.

Structure

and Purpose of the Series

This series

consists of three parts, each examining the operative conditions of

contemporary art and the points at which those conditions have lost their

effectiveness. The aim is not to propose new theoretical solutions, but to

clarify the consequences produced by the judgmental and institutional

structures that contemporary art has long taken for granted.

Part 1 examines

how the suspension of judgment, once intended as a critical strategy, became

fixed through repetition and transformed into structural evasion.

Part 2 analyzes

the post-discursive condition in which value judgments are increasingly

replaced by capital, visibility, networks, and narrative connectivity.

Part 3 considers

the position of Korean contemporary art within these conditions, exploring how

it might move from the role of discursive respondent to that of a point of

conceptual departure.

Moving

Forward

The

objective of this series is not to provide answers. The challenges facing

contemporary art cannot be resolved through new declarations or fashionable

concepts. What is

required first is a clear recognition of what no longer functions: how judgment

has been deferred, how critique has been neutralized, and how responsibility

has been obscured.

Accordingly,

this series seeks to establish a theoretical foundation through which Korean

contemporary art can move beyond mere participation in global contemporary

discourse and instead become a site for analyzing and questioning the

conditions that shape it. In this sense, the project constitutes a necessary

and unavoidable task for any serious discussion of the future of Korean

contemporary art.

The future

does not arrive through the declaration of new forms. It becomes possible only

when existing conditions are recognized as no longer sufficient, and when those

conditions themselves are transformed into objects of thought.

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.