Anxiety Behind

the Glitter

Today,

contemporary art appears more dazzling than ever. Art fairs around the world

draw hundreds of thousands of visitors, and record-breaking prices are set at

auctions.

A large crowd gathers in front of Mark Bradford’s work, which achieved the highest price of KRW 6.7 billion (approx. USD 50 million) at Frieze Seoul 2025.

In Korea as well,

Frieze Seoul has become a focal point for the Asian art market, while regional

fairs such as Art Busan and Art Gwangju continue to expand. Social media feeds

are flooded with exhibition snapshots, and blockbuster shows draw long lines of

eager visitors. Yet behind this spectacle lies a deep unease. The meaning of

works and the essence of art are increasingly sidelined, replaced by prices,

brands, and images. This is what we may call the “age of role reversal.”

What Does Role

Reversal Mean?

Role reversal is

not a mere rhetorical flourish. It refers to the condition in which what should

be the purpose is reduced to a means, and instruments or external markers come

to dominate the essence itself.

The essence of

art lies in creation, aesthetic exploration, and autonomy. But today this

essence is no longer allowed to function; instead, market logic and image

consumption reign as if they were the essence. Should we accept this situation

as a new paradigm, or regard it as a distortion where the essential is

overshadowed by the inessential? This is the existential question that

contemporary art must confront.

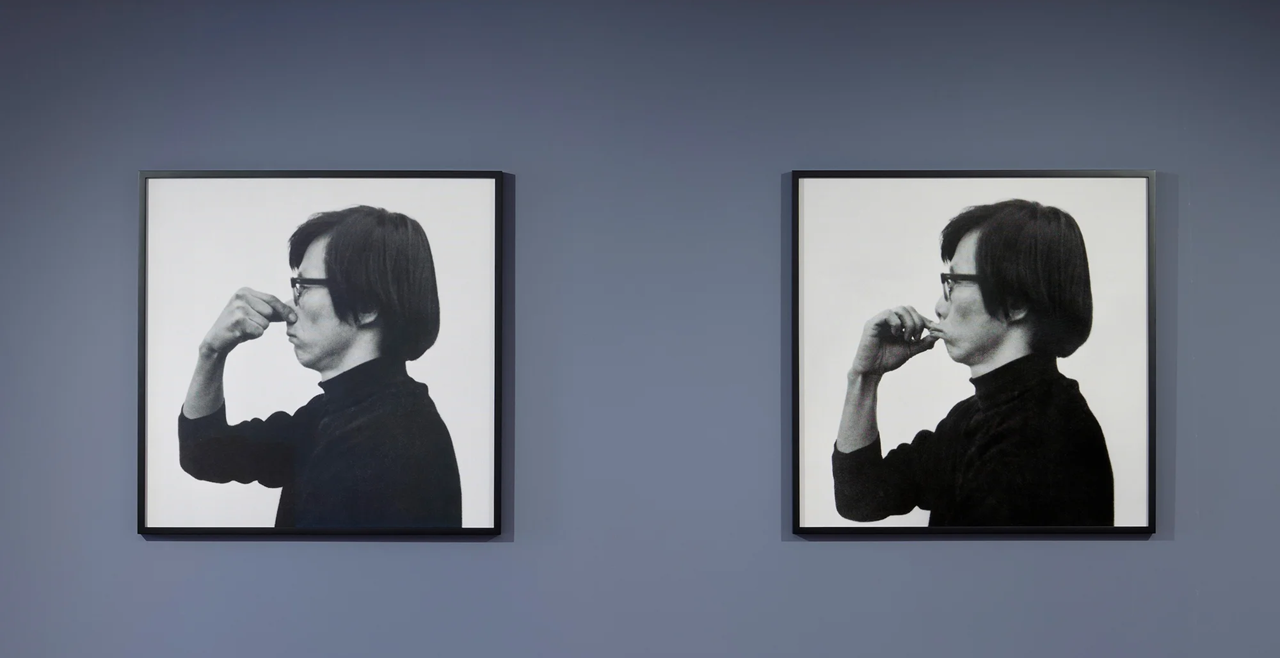

The exhibition view of Lee Ufan’s paintings in《Korean Abstract Art: Kim Whanki and Dansaekhwa》at the Powerlong Museum, Shanghai (2019). / Photo: Seoul Economic Daily

The exhibition view of Lee Ufan’s paintings in《Korean Abstract Art: Kim Whanki and Dansaekhwa》at the Powerlong Museum, Shanghai (2019). / Photo: Seoul Economic Daily

The Korean

Context: From Dansaekhwa to Young Artists

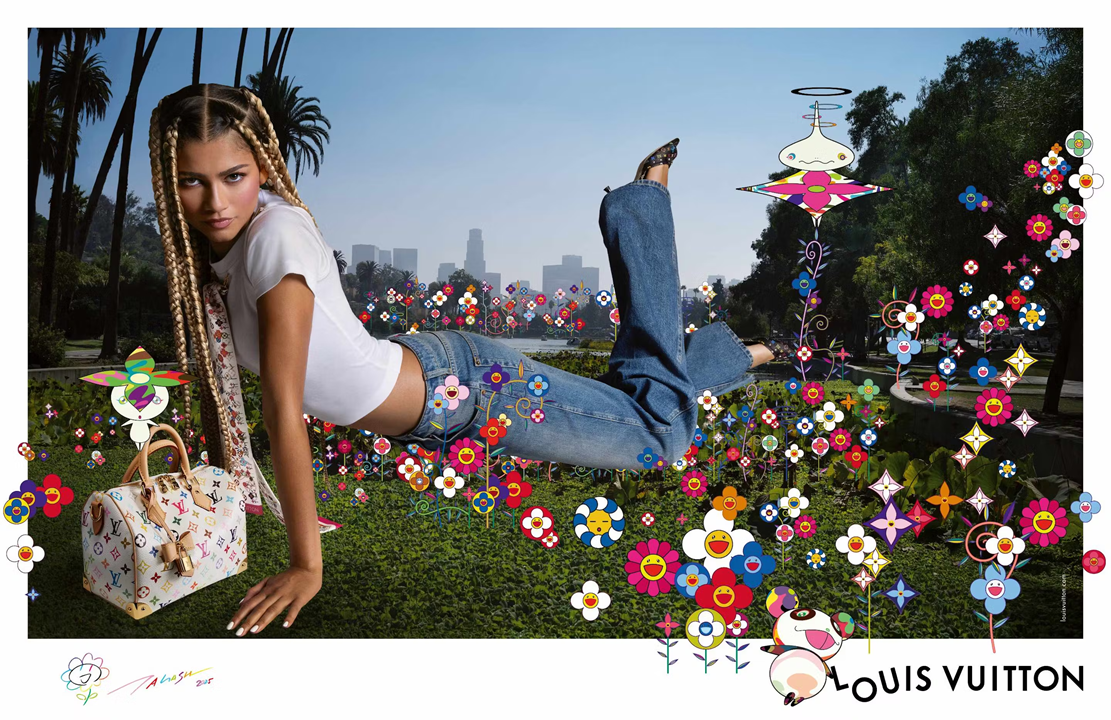

Let us first look

at the Korean scene. Over the past decade, ‘Dansaekhwa’ (Korean

monochrome painting) gained international recognition and became branded as “Korean

modernism.” Yet its discourse was consumed less as aesthetic achievement than

as a marketable cultural brand and investment vehicle. A similar trajectory is

evident among younger artists: rather than the content of their work, what

comes first is the label—“a rising artist you must buy now.” The artwork

becomes a certificate of market value, while the inner meaning of creation is

pushed aside.

The late Park Seo-Bo’s Dansaekhwa paintings were reinterpreted through LG’s color and AI technology and showcased at Frieze Seoul 2025.

View of the LG OLED TV Lounge at Frieze Seoul 2025, held at COEX, Seoul.

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days(2021), the first NFT artwork auctioned at Christie’s, sold for USD 69.3 million. / Courtesy of Christie’s

The Global

Context: Branded Artists and the NFT Bubble

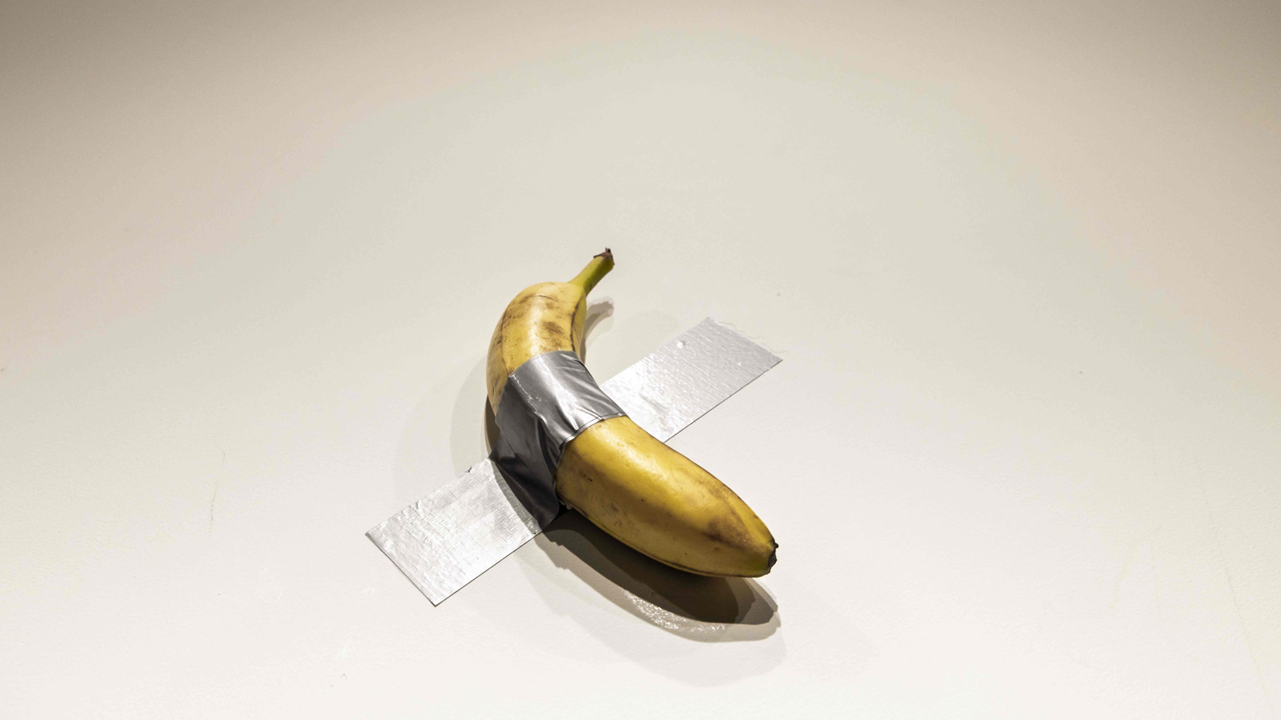

Globally, the

situation is little different. Artists like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst wield

more power as brands and commercial icons than through the intrinsic content of

their work. The NFT boom was a quintessential case in which “scarcity

guaranteed by blockchain” was packaged as artistic value regardless of artistic

substance. When the hype subsided, what remained was a speculative bubble and a

collapse of trust. Art has become subsumed under a new regime of value—sign

capitalism—where signs and capital are inseparably fused.

Gettin' Busy Balloon Dog Sculpture / Photo: artofplay.com

What Is Sign

Capitalism?

“Sign capitalism”

refers to a system in which capital is no longer confined to material

production but circulates through images, brands, and signs as exchange values

in themselves.

Korean artist Cody Choi’s ‘Animal Totem’ (1999) was converted into an NFT work and valued at 70,000 Ethereum (approx. USD 1.75 billion).

Jean Baudrillard’s

notion of sign-value pointed out that commodities are consumed not

merely for use or price but for the symbolic meanings they carry. Contemporary

art epitomizes this condition. Works are evaluated not for intrinsic merit but

for signifiers such as “represented by a major gallery,” “number of followers,”

or “auction price.”

Here, Pierre

Bourdieu’s theory adds a crucial insight. He understood art as a field

structured by relations of power, in which “cultural capital” and “symbolic

capital” determine legitimacy. The value of a work, therefore, arises less from

the work itself than from its position within the field of institutions,

critics, galleries, and collectors. What we now witness—brand over work,

validation over meaning—is the extreme signification of symbolic capital.

Maurizio

Lazzarato, in 『Signs and Machines』, described contemporary capitalism as a system that mobilizes signs

and desires. Capital no longer simply exploits labor but organizes

imagination, signs, and consumer desire to generate new value. Contemporary art

sits squarely within this structure. Works function as devices of desire, while

social media snapshots and art fair sales exemplify what Lazzarato called the “economy

of signs and desires.” From this perspective, art today is less an autonomous

act of creation than a sign-machine deployed to organize and channel

desire.

The

Transformation of Exhibitions: From Contemplation to Certification

Exhibitions too

have changed character. In Korea, Ron Mueck’s show attracted over half a

million visitors in three months, yet the focus of many was not the work’s

meaning but the photos they could post online.

MMCA’s exhibition《Ron Mueck》/ Photo: The Joong Ang Ilbo

MMCA’s exhibition《Ron Mueck》reached 500,000 visitors within 90 days (April 11–July 9, 2025).

Globally,

immersive exhibitions such as teamLab and Van Gogh Alive turn art into a

consumable experience rather than an occasion for contemplation. Exhibitions

become stages for event industries, while artworks are reduced to backgrounds

for image consumption. Such transformations reinforce art’s subordination to

the order of sign capitalism.

The Structure

of Distortion

This inversion

has multiple causes.

First, in late

capitalism, art has been financialized into a tradable asset, subject to graphs

of rising and falling prices.

Second, digital

transformation and social media fragment works into images, compressing viewing

time into instant consumption.

Third,

institutional authority has weakened. Where once criticism and public museums

provided criteria for value, they now rely increasingly on box-office metrics

and public sentiment. Art loses the ground to stand on its own, collapsing into

an inessential apparatus governed by external indicators.

The Question

of Value Production

Who, then, is the

true producer of value? The artist, the public, the institutions, or capital?

Today, value production is distributed. In Korea, entry into an art fair often

carries more weight than a museum exhibition. Globally, collectors, institutions,

and even algorithms wield greater influence than artists themselves. But this

pluralization of value leads to a dilution of essence. Works mean less as works

in themselves than as signs circulating within networks. This is precisely the

intersection of what Bourdieu called the monopolistic force of symbolic capital

and what Lazzarato described as the machinery of desire.

Alternative:

Reconstructing Trust

We cannot simply

accept this as an inevitable paradigm of our time. It is a distortion in which

essence is overshadowed by the inessential. The alternative lies in

reconstructing trust. Of course, we cannot return nostalgically to the past

ideals of autonomy and the sublime. Instead, new structures of trust must be

built. Criticism must once again provide public language, museums and

institutions must resist surrendering entirely to market logic, and art must be

anchored in communal values, ethical practices, and sustainability.

Conclusion:

Returning to the Existential Question

The “age of role

reversal” is not a passing phenomenon but the name of an existential crisis

facing contemporary art. In both Korea and the world, art still retains its

essence, but that essence is being devoured by the structure of sign

capitalism. In Bourdieu’s terms, the art field is dominated by the

monopolization of symbolic capital; in Lazzarato’s, art has been reduced to a

sign-machine for the organization of desire.

The question we

must now grasp is clear: For what does art exist? Without sustained

reflection and an answer to this, contemporary art will remain lost in the

noise of markets and images. Only by holding fast to this question, and by

rethinking essence itself, can we prepare to move beyond the age of role

reversal.

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.