Do Ho Suh’s Some/One presented at “Art Basel Miami Beach 2025” / Photo: Art Basel Facebook

At Lehmann Maupin’s booth at last week’s “Art Basel Miami

Beach 2025”, Do Ho Suh’s seminal work Some/One (2014)

made an immediate visual impact.

The work was acquired by a collector on the fair’s second

day for 1 million USD and is reportedly destined as a promised

gift to a major American museum. Another version of this piece is

known to be in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum.

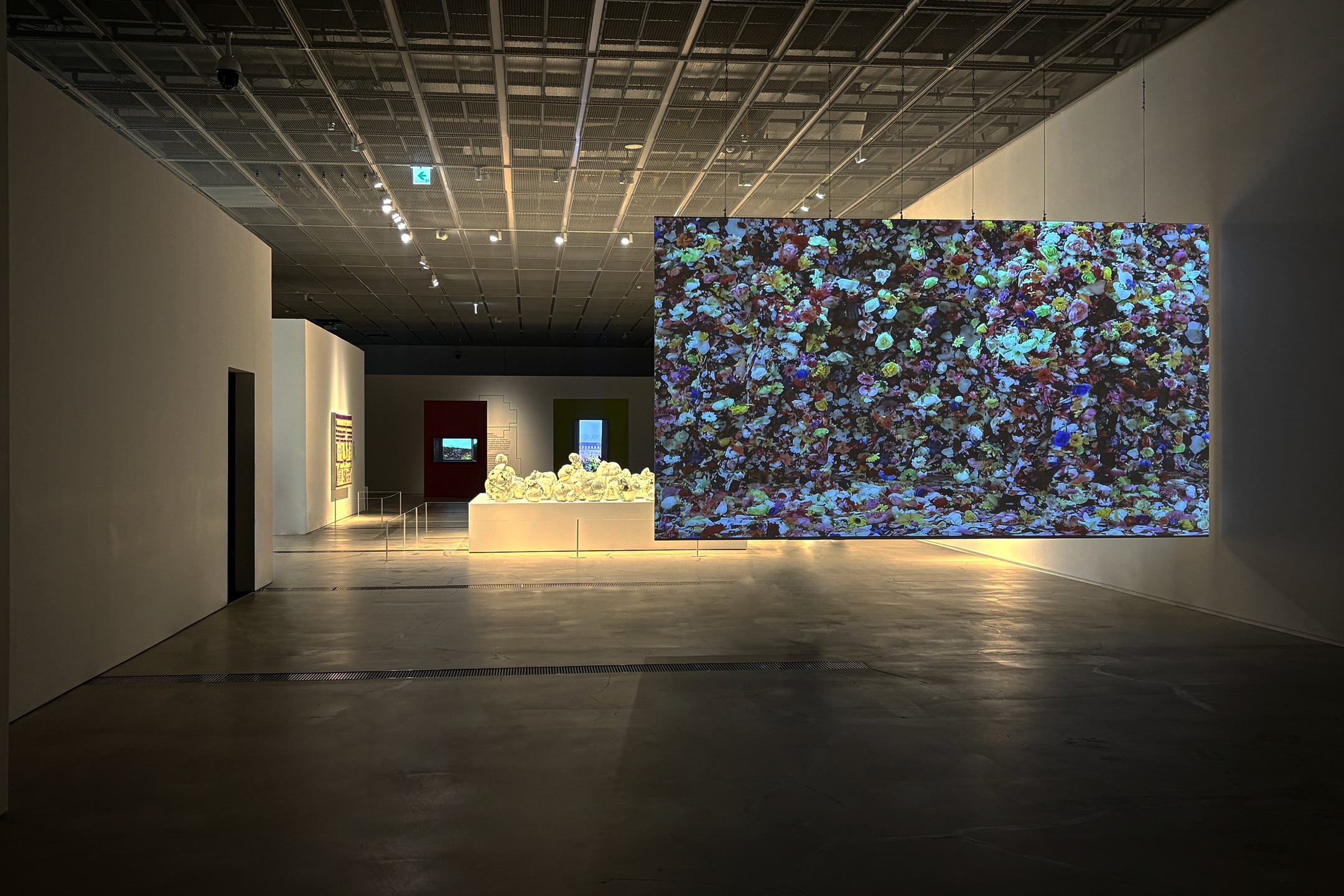

Some/One (2001), installation view at the Seattle Art Museum / Photo: Seattle Art Museum

Created in 2014, the work emerged from Suh’s attempt to move

beyond the individual and delve into questions of collective and public

identity.

The structure, which resembles a suit of armor or ceremonial

garment, is hollow inside, while its outer surface is composed of tens of

thousands of ‘dog tags’. These countless shimmering metal identity plates,

linked together into a kind of protective shell or ritual figure, embody the

tension between individual and collective, and visualize how a single

person’s existence can be revealed or erased within a larger group. Dog tags

function as devices for identifying individuals, but within this work they are

anonymized and operate as endlessly repeated units.

This sculpture does not narrate a story. It does not

explicitly reference the military, the nation-state, or any specific society.

Instead, it uses form to show how individuals are absorbed and standardized

within collective and institutional structures. While this inquiry grows out of

experiences tied to Korean society, it refuses to confine those experiences to

a single cultural case study. It is precisely at this point that Some/One

becomes a work that can be read anywhere in the world.

Do Ho Suh, Installation View of High School Uni-Form

(1997)

Do Ho Suh, Installation View of High School Uni-Form

(1997)Suh’s preoccupation with these issues is already evident in

his late-1990s school uniform works. In High School Uni-Form

(1997), identical uniforms are arranged in a grid, presenting a structure in

which the shape of the collective remains while the individual is conspicuously

absent. The school uniform is an institutional shell imposed during

adolescence, yet in the work it appears only as a repeated form from which the

body has been removed.

Do Ho Suh, Uni-Form/s: Self-Portrait/s: My 39 Years,

169 × 56 × 254 cm, 2006

Do Ho Suh, Uni-Form/s: Self-Portrait/s: My 39 Years,

169 × 56 × 254 cm, 2006The questions posed in the uniform works are further

condensed in Some/One. The uniform of the education

system is extended into the insignia of the nation-state, and a multitude of

discrete objects coalesce into a single bodily figure. Without emotional excess

or explanatory rhetoric, Suh pushes his inquiry forward through form alone.

This method is a consistent hallmark of his practice.

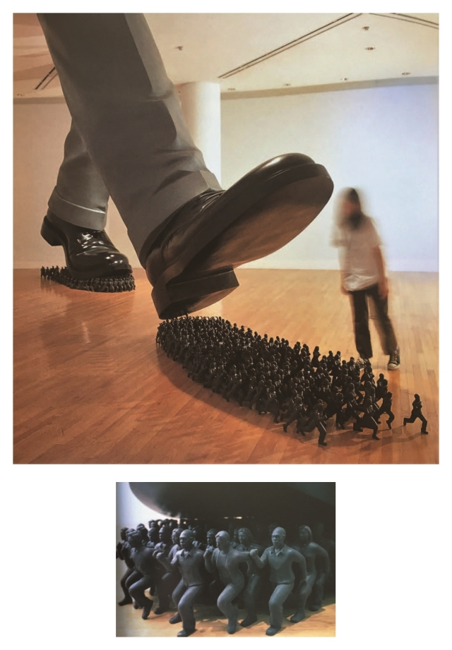

Do Ho Suh, Karma, FRP, 389.9 × 299.7 × 739.1 cm, 2003, installation view at Art Sonje Center

The reason Do Ho Suh is often cited as an artist

representative of Korea is not because he “shows Korean imagery” particularly

well. Rather, it is because he succeeds in transforming Korean experiences into

a structure of perception that can be understood universally, precisely by

refusing to foreground “Koreanness” as a theme.

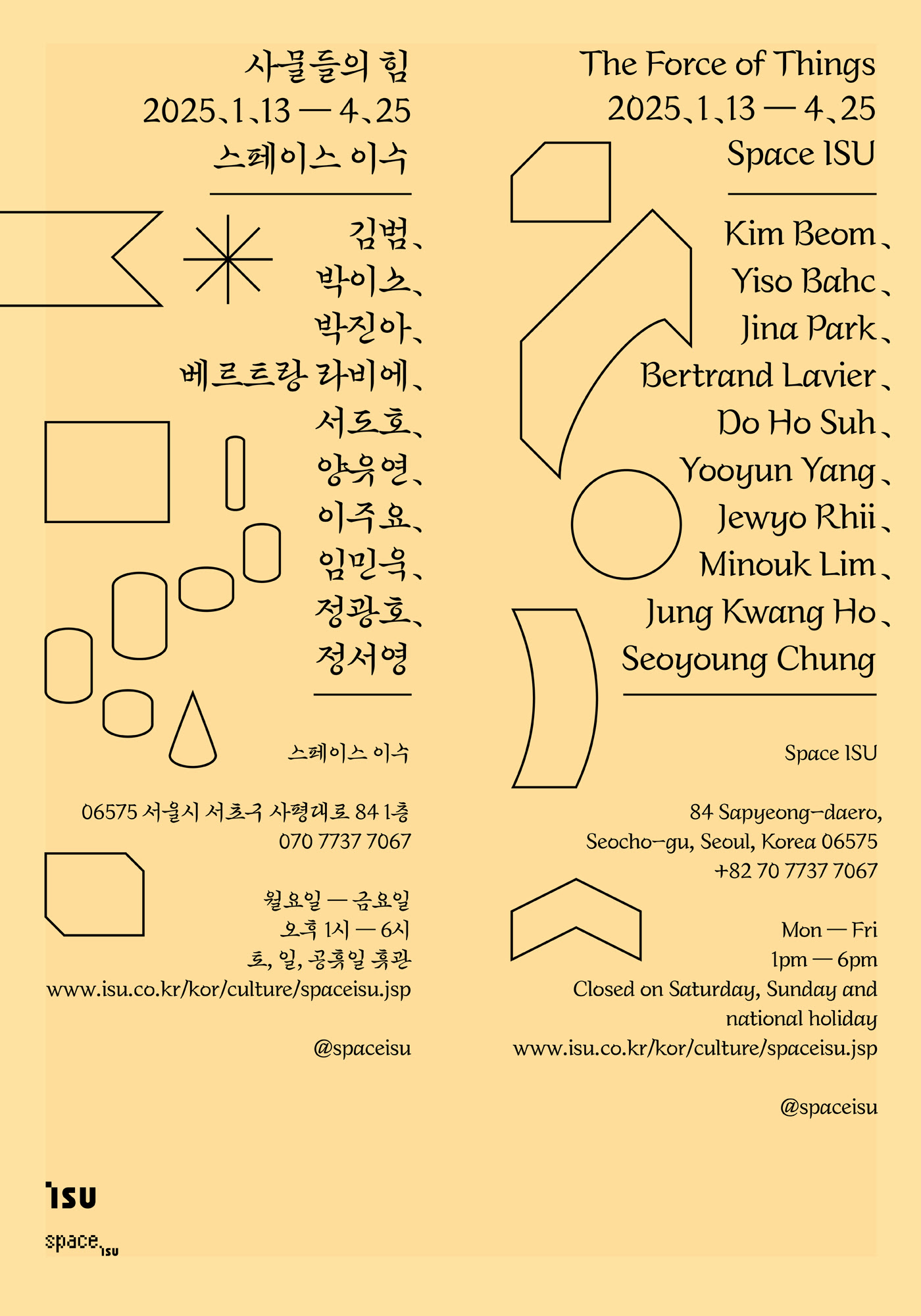

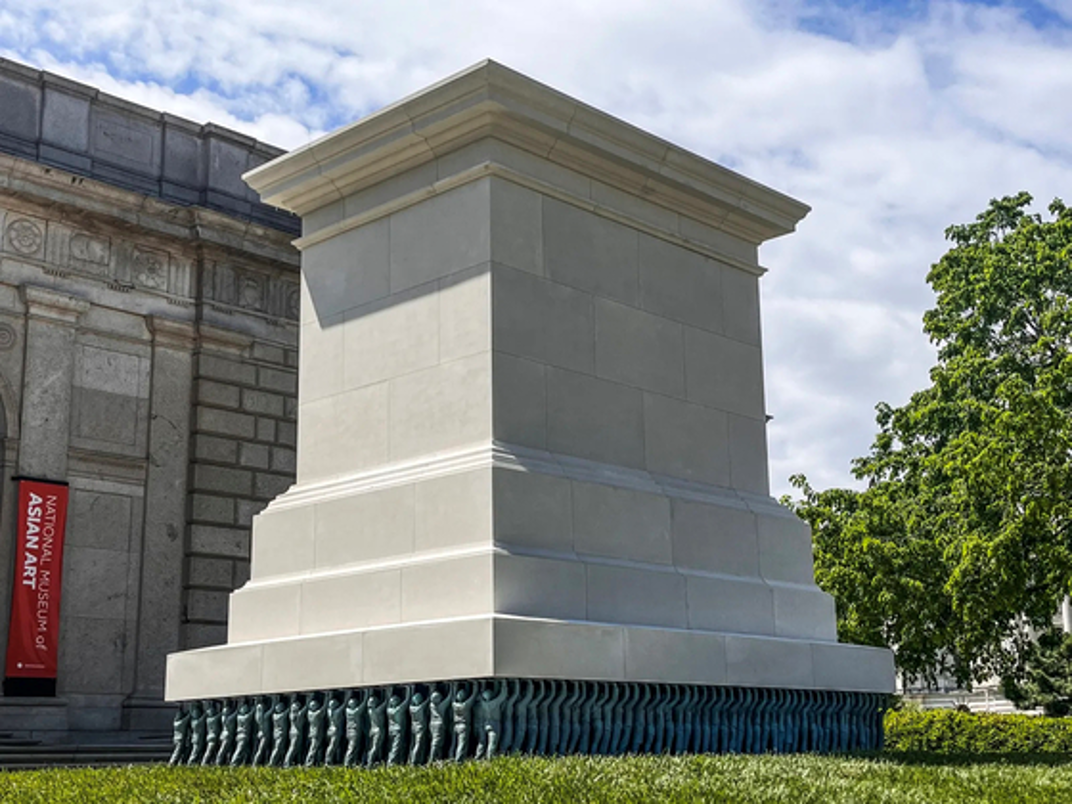

Do Ho Suh’s Public Figures were installed in the courtyard of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C., in April this year. The work, commissioned to mark the museum’s 100th anniversary, will remain on view for five years. / Photo: Smithsonian Magazine

This carries significant implications for the overseas

expansion of Korean contemporary art. It suggests the possibility that works

can “operate on their own” without requiring additional explanation of context

or cultural difference. Suh’s practice exemplifies a mature pathway through

which Korean artists can encounter and engage with the global art world.

Some/One is not a work that

simply “represents” a particular region or issue; it can be read as a sculpture

addressing structural sensibilities shared across contemporary societies. The

tensions between the individual and the group, discipline and protection,

sameness and anonymity are questions that resonate globally, and this work

crystallizes them into form. As a result, the piece does not remain a one-off

spectacle; it is continuously revisited through major exhibitions and

collections. Its reappearance at this year’s “Art Basel Miami Beach 2025” is

part of this ongoing accumulation.

The presentation of Some/One at “Art

Basel Miami Beach 2025” signals that the overseas presence of Korean artists is

no longer an exceptional event, nor merely a matter of “going abroad.” It is an

important sign that works shaped within the Korean context are now being read

within the shared visual and conceptual language of global contemporary art.