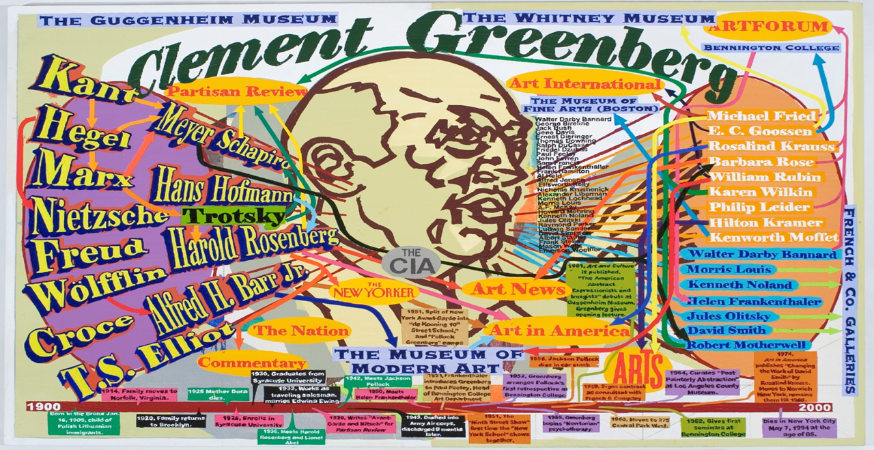

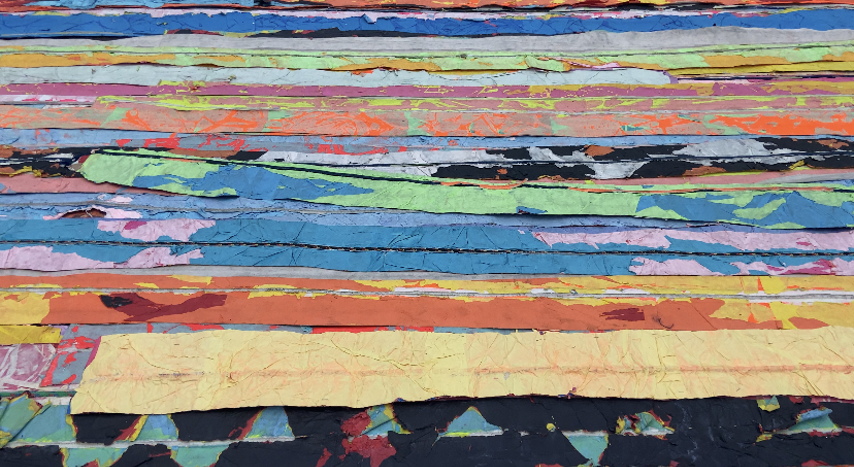

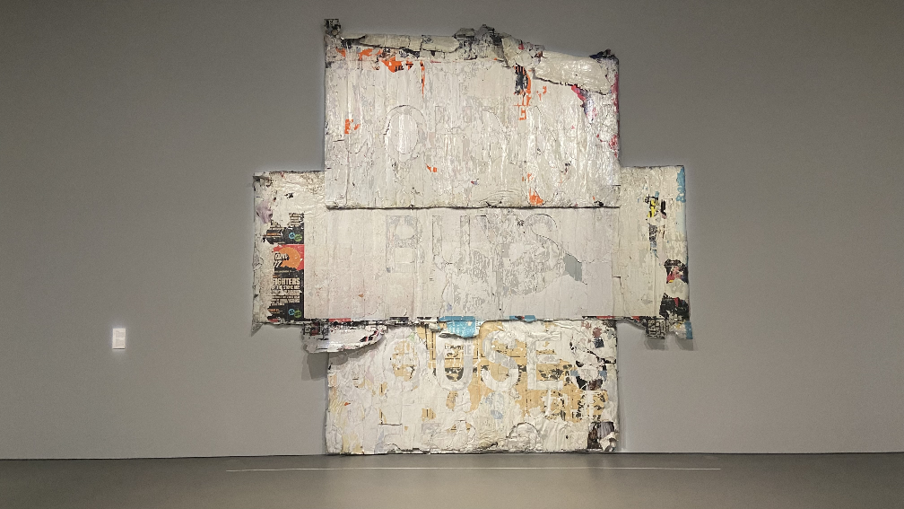

Mark Bradford, Float, Installation view, 2019, Mixed media. ©K-ARTNOW

Mark Bradford, Float, Installation view, 2019, Mixed media. (Detail) ©K-ARTNOW

Bradford’s work

is often packaged under the label of “social abstraction.” Yet this term

directly contradicts the foundations of abstraction itself and functions more

as a sanitized institutional rhetoric that half-erases its ethical and

political implications. Abstraction was historically built on removing

narrative and context, but Bradford’s surfaces contain direct traces of

specific racial, class, and urban structures.

These traces are not mere

materials; they are fragments of information embedded with the lived realities

of particular communities. However, once such information is rearranged into an

abstract composition, its content becomes blurred, its meaning encrypted, and

its political sharpness neutralized.

Ultimately, his

works are too specific to be called abstraction, and too harmless to be

considered political practice. This contradictory tension is precisely the

space Bradford occupies, and “social abstraction” serves mainly to mask that

instability as an institutional euphemism.

A Lack of

Formal Density

It is true that

Bradford’s works produce a strong visual first impression. But visual impact

cannot substitute for structural completeness. His surfaces are repeatedly

constructed through similar methods of scraping, tearing, and layering—processes

that tend to unfold less through deliberate formal judgment than through

material contingency.

The monumental scale of his canvases can create an

illusion of depth, but once one moves into the details, the formal

decision-making proves loose and repetitive. The structural tension and

chromatic organization historically central to abstraction do not play a

decisive role in his work.

(L) Crying is Easier Than Change, 2024, Mixed

media on canvas / (R) Blood Beats, 2024, Mixed media on

canvas ©K-ARTNOW

(L) Crying is Easier Than Change, 2024, Mixed

media on canvas / (R) Blood Beats, 2024, Mixed media on

canvas ©K-ARTNOWThis reveals how the common discourse framing

Bradford’s work as an ‘expansion of abstract painting’ significantly

overestimates its formal weight. Surface complexity does not automatically

produce formal depth, and Bradford’s work does not fully bridge that gap.

Rearranging an Old Discourse

The language that celebrates Bradford’s work as

innovative overlooks a major lineage in American art from the 1990s and 2000s.

Installation view of the 1993 Whitney Biennial Exhibition (Whitney

Museum of American Art, New York, February 24–June 20, 1993).

Installation view of the 1993 Whitney Biennial Exhibition (Whitney

Museum of American Art, New York, February 24–June 20, 1993).Ida Applebroog, ‘Marginalia’ series (1992);

Ida Applebroog, Jack F: Forced to Eat His Own Excrement (1992); Ida Applebroog, Kathy W.: Is Told that If She Tells Mommy Will Get Sick and Die (1992). Photograph by Geoffrey Clements

This installation uses Black caricatures, folkloric imagery, and historical stereotypes to expose the embedded racism and visual violence within American culture. The large paintings on the walls and the scattered panels on the floor repeat cartoon-like and folkloric representations, distorted Black figures, and exaggerated racial tropes. As viewers walk through the space, they confront this structure of visual violence directly. Rather than presenting a single image, the work constructs an environment that allows the audience to experience how Black identity has been distorted, represented, and consumed throughout history.

For decades, American institutions and critics

have treated race, urban violence, poverty, class division, and gentrification

as central themes. The 1993 Whitney Biennial stands as a

defining moment in foregrounding these issues. During this period, many artists

rigorously experimented with translating social structures and systems of

violence into abstraction, diagrammatic languages, symbolic forms, and

material residues.

David Hammons, Oh Say Can You See, 2017 / Source: The Pinault Collection

This work replaces the colors of the U.S. flag with those of the Black Liberation Movement, fundamentally questioning the foundations of American national identity. Red signifies the history of bloodshed and violence endured by Black communities; black represents the Black body, identity, and political existence; green symbolizes the future, hope, and vitality of the African diaspora. The torn and damaged surface materializes these historical scars, making the work one of the most powerful moments in Black conceptual art to subvert a national symbol.

Notably, Black artists such as David

Hammons and Betye Saar developed

strategies far earlier than Bradford to translate structural racism, urban

fractures, and the memories and violences within Black communities into painterly,

sculptural, and collage-based languages.

Hammons transformed urban debris, bodily traces,

and street materials into political symbols, foregrounding institutional

critique and the sensory weight of Black identity. Saar, in turn, constructed

assemblages from the histories of Black women, family, and the civil rights

movement, working to overturn racist iconography decades before Bradford. Their

practices established a formal and conceptual vocabulary that

restructured social forces, violence, and communal memory into visual

form long before Bradford’s rise.

Exhibition view of Mark Bradford’s Solo Exhibition ©K-ARTNOW

Given this lineage, the themes Bradford engages—urban

fracture, racial politics, and the historical residues of Black communities—function

less as novel proposals and more as repackaged versions of already

institutionalized discourse. His work unites abstraction and

social reality, but it does so by repeating a long-established set of

linguistic and material strategies within Black artistic practice. Bradford

therefore occupies a position not of avant-garde innovation, but of market-friendly

and institutionally optimized recontextualization.

The Safety of Political Content and

Institutional Convenience

Bradford’s work is often described as political

because it addresses race and class. But the politics his work actually

performs is calibrated to institutional needs. Conflict becomes diffuse

structural trace; violence is absorbed into abstract pattern; messages disperse

into ambiguous metaphor.

Manifest Destiny, 2023, Mixed media on canvas ©K-ARTNOW

This work reveals the realities of urban development in America and the structure of capital power that drive it.

Such strategies convert political radicality

into an aesthetic signal easily absorbed by major institutions—precisely the

mode favored by the global art system today: works that contain political

subject matter while evacuating genuine critical force. Bradford’s practice

provides “safe politics,” a consumable form of radicality.

Mark Bradford, Installation view of《Keep Walking》 ©K-ARTNOW

An Artist Who Stays on the Threshold

Bradford is often praised for expanding the

boundary between abstraction and politics. In reality, his work remains on that

boundary, maintaining a stable equilibrium rather than crossing it. The

conflict between the concept of abstraction and the specificity of his

materials, the looseness of his formal decisions, the repetition of

pre-existing discourses, and a politics optimized for institutional circulation—together,

these elements show that his language is not “new,” but moderated by

institutional demands.

Reading Bradford’s exhibition critically

therefore means looking beyond the works themselves to the broader system that

shapes contemporary art: What does the art institution consume under the name

of the political? What does it remove? What forces determine the form in which

politics appears? These are the essential questions this exhibition urges us to

consider.

Exhibition Information

Exhibition title :《Mark Bradford: Keep Walking》

Dates: August 1, 2025 (Fri) – January 25, 2026 (Sun)

Venue: Amorepacific Museum of Art, 100 Hangang-daero, Yongsan-gu, Seoul

Opening hours / Closed: Tue–Sun 10:00–18:00; closed Mondays, Jan 1,

Lunar New Year & Chuseok holidays

Exhibition contents: Approx. 40 works including paintings,

installations, and video. Highlights include Blue

(2005), Niagara (2005), the 2019 installation Float,

and a newly commissioned series for the museum.

Admission: Adults 16,000 KRW (discounts available for students and

youth)

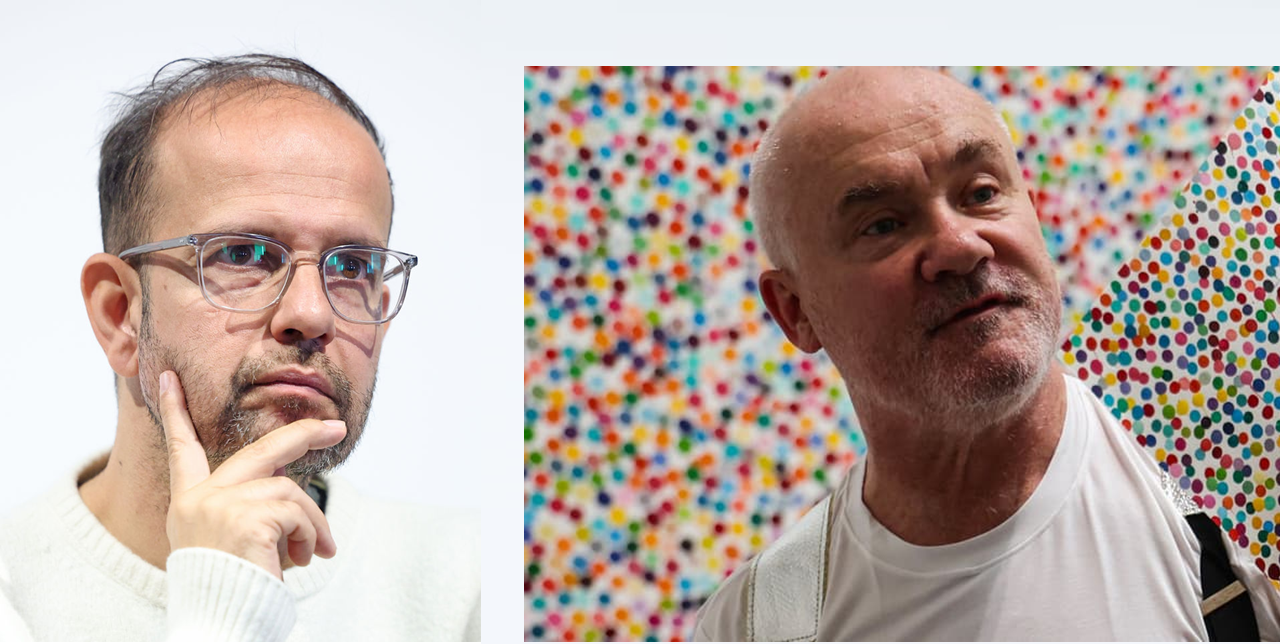

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.