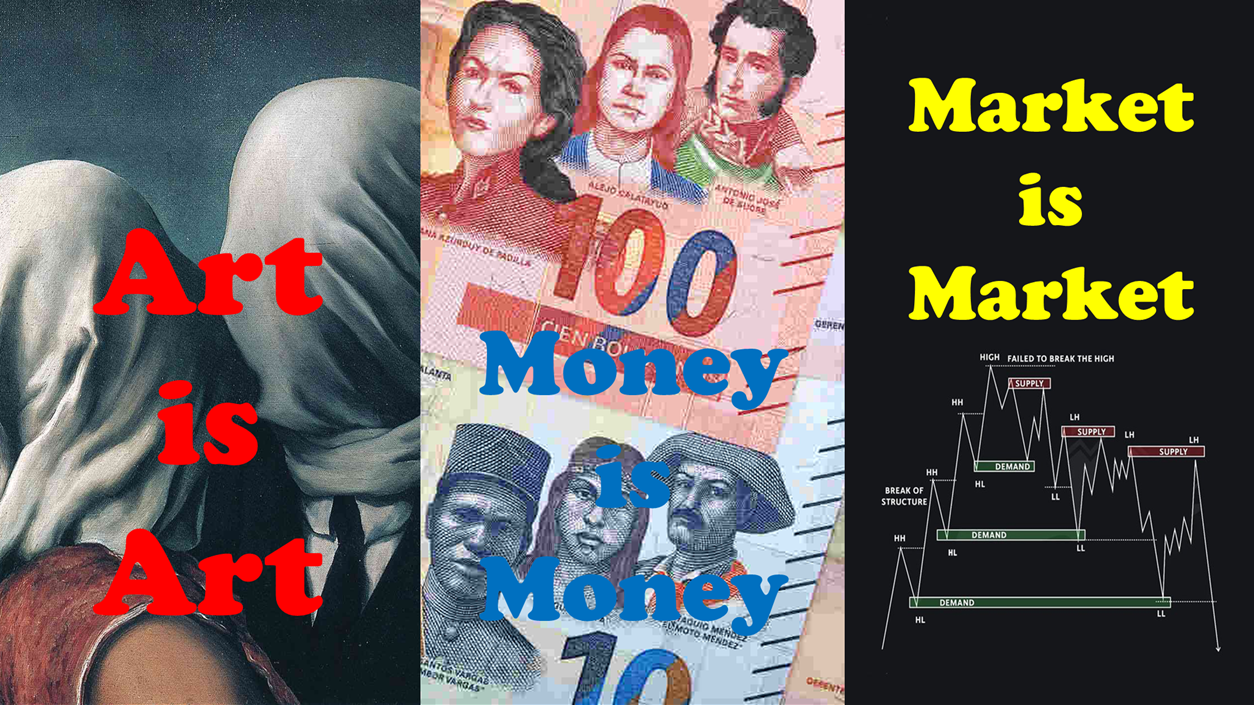

In contemporary life, we often speak

of “value,” yet rarely do we pause to examine what we mean by it. Under

capitalism, value is almost instinctively reduced to a single measure: price.

Art is no exception. The inherent meaning of a work—its inner necessity and

expressive urgency—has gradually been pushed aside, while marketability and

investment potential increasingly dictate how art is evaluated and consumed.

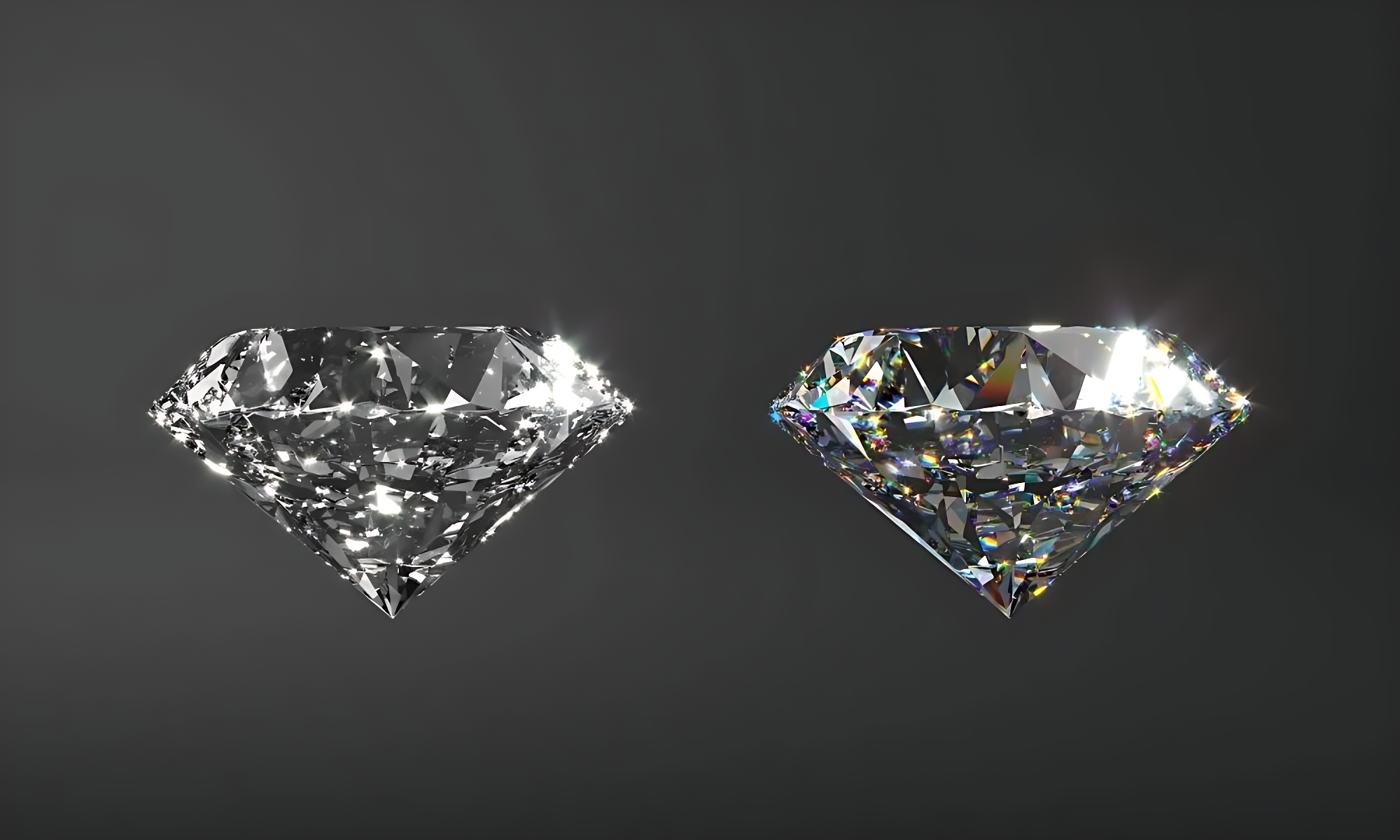

Every commodity possesses two types of

value: use value and exchange value. Use value refers to an object’s

utility—its capacity to serve a specific function. A chair provides a place to

sit; clothes provide coverage. In contrast, exchange value reflects the

object’s worth in the marketplace—its relative equivalence to other goods, most

commonly expressed as price.

The critical point is that these two

values are not necessarily aligned. Some things are undeniably useful yet

undervalued, while others, lacking real utility, may still command high prices

due to rarity or symbolic significance. This imbalance lies at the heart of

capitalism and mirrors the structural crisis that contemporary art now

confronts.

When applied to art, the distinction

becomes more layered. The use value of an artwork is not found in physical

utility but in its ability to evoke emotion, provoke thought, and offer moments

of introspection or transformation.

Art can move the viewer, prompt

existential questions, or redirect one’s orientation toward life. Its function

transcends the material; it resonates deeply within the human psyche.

However, in today’s art world, such

inner resonance is often overshadowed by art’s role as a commodity—an

investment, a status symbol. Its exchange value is determined by factors

external to the work itself: the artist’s brand, auction history, exhibition

record, or the prestige of collectors. Over time, this exchange value has come

to dominate and even displace art’s intrinsic value.

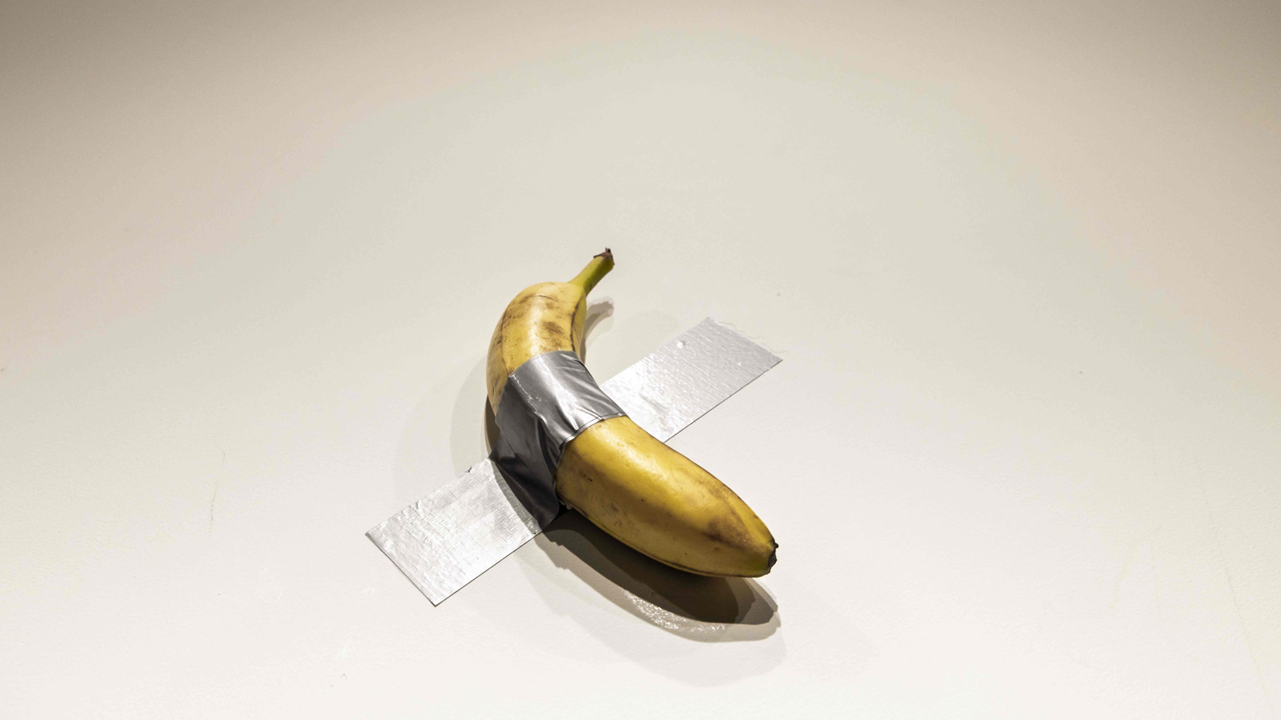

The crisis emerges most clearly when

these two forms of value are conflated. We now approach artworks by asking,

“How much is it worth?” rather than “What does it mean?”

Emotional impact and conceptual depth

are eclipsed by rankings, price tags, and market trends. Even worse, we

increasingly assume that high-priced art is inherently better. This distortion

subjects art to the mechanisms of capital and obscures its essence—its

authenticity, subjectivity, and the ethical imperative of creation.

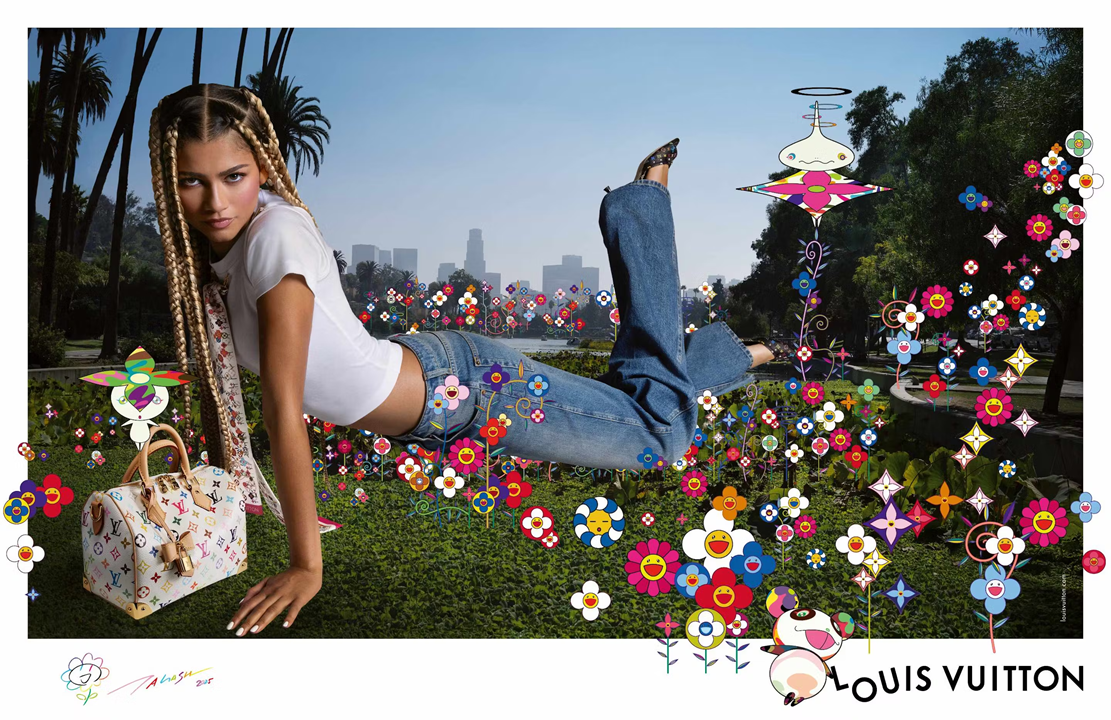

What’s more troubling is how this

confusion reshapes artistic practice itself. Many artists now feel compelled to

produce what will sell or stand out in the marketplace, rather than what they

truly need to express. The pursuit of “selfhood” gives way to the logic of

“market fit.” As a result, art begins to mimic the conditions of a product

rather than remain a site of personal or philosophical inquiry.

The structural distortion of value in

art today is not an abstract philosophical concern—it is a concrete, lived

condition across the art ecosystem.

Galleries have increasingly shifted

away from being partners in artistic experimentation, becoming instead

sales-driven spaces that prioritize turnover. Exhibitions are less about

intellectual inquiry and more about presenting “consumable images” to the market.

Emerging artists, in particular, are often forced to reproduce commercially

viable styles to ensure survival. In this process, the authenticity of creation

and the autonomy of the artist are deeply compromised. The gallery no longer

seeks to discover or nurture value—it mediates only what is likely to sell.

Art fairs, now a default fixture in

the global art calendar, reinforce this shift. Artists are expected to produce

new work on a schedule dictated by visibility, not by reflection. The artwork

becomes less a result of contemplation and more a product designed for

exposure. As art is absorbed into cycles of velocity and surface, it loses its

character as a space for thought. Exhibitions cease to be contemplative

environments; artworks become objects marked by price tags rather than

presence.

The logic of the auction house further

entrenches this paradigm. Auctions have become key indicators of an artist’s

market value, yet their standards of evaluation rest solely on the question of

saleability. Aesthetic depth, philosophical content, and historical context

rarely enter the frame. The hammer price becomes both the means and the

message. Once circulated through the auction market, artworks are treated not

as unique cultural objects, but as liquid assets—interchangeable, expendable,

and designed for profit.

Even the role of the collector has

shifted. Once imagined as a cultural partner, the contemporary collector often

operates as a short-term investor. The goal is not to accompany an artist’s

evolution, but to maximize gains through strategic acquisition and resale.

Artists are “boosted” by market players through PR and institutional

positioning, only to be sold off when the price peaks. Dealers, consultants,

and even critics have aligned themselves with this speculative infrastructure.

Art is increasingly reduced to “marketable imagery,” and artistic practice

becomes a process of brand repetition.

This is the very expression of vulgar

capitalism in the art world—capitalism stripped of ethos and historical

consciousness, focused solely on turnover and spectacle. It masquerades as

cultural vitality, but behind the façade is an accelerating erosion of art’s

philosophical and ethical foundation. Art becomes something to be priced,

possessed, and flipped, rather than lived with, questioned, and contemplated.

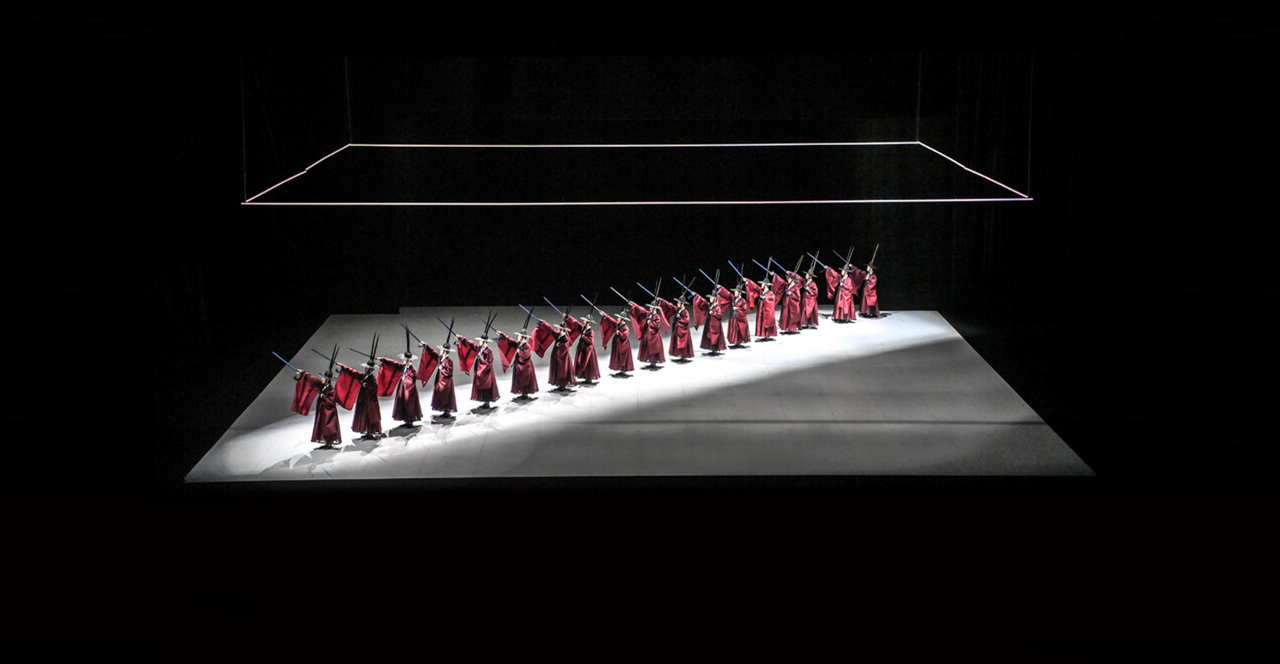

And yet, art was never meant to be

efficient. At its core, it carries the usefulness of the useless. It is not

decoration, nor is it merely an object of ownership. Rather, it is a unique

language that awakens perception, surfaces the unconscious, and invents new

grammars of emotion and thought. Its intrinsic value cannot be measured in

price, nor can it be fully explained through use value or exchange value. It

exists only in the convergence of the artist’s vision, lived experience,

expressive method, and authentic being. The moment art is reduced to use value

or exchange value, it loses its reason for being.

We

must therefore rethink how we engage with art. The question is no longer “How

much is this work worth?” but rather “What does it express—and, more

profoundly, why does it exist?” This is where the essence of art lies: in its

capacity to create, to move, and to reveal beauty. And it is this very

ground—authentic, irreplaceable, and human—that art must reclaim against the

tide of vulgar capitalism in this age of reification.

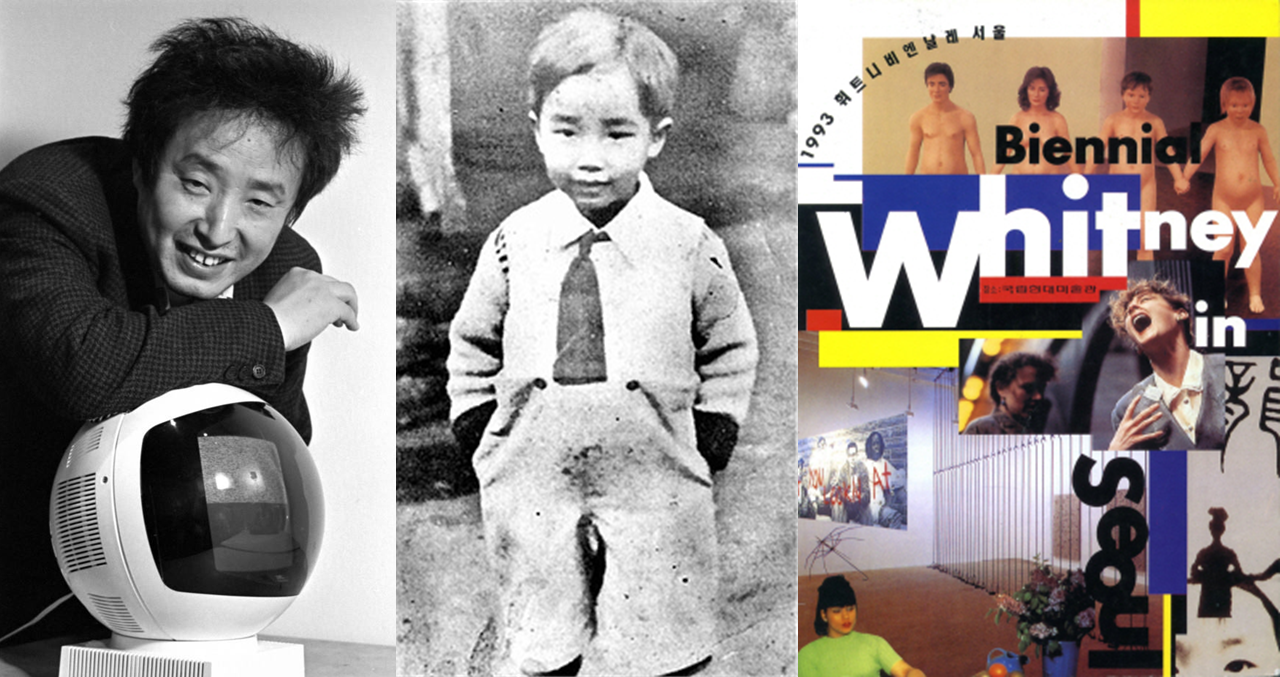

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.