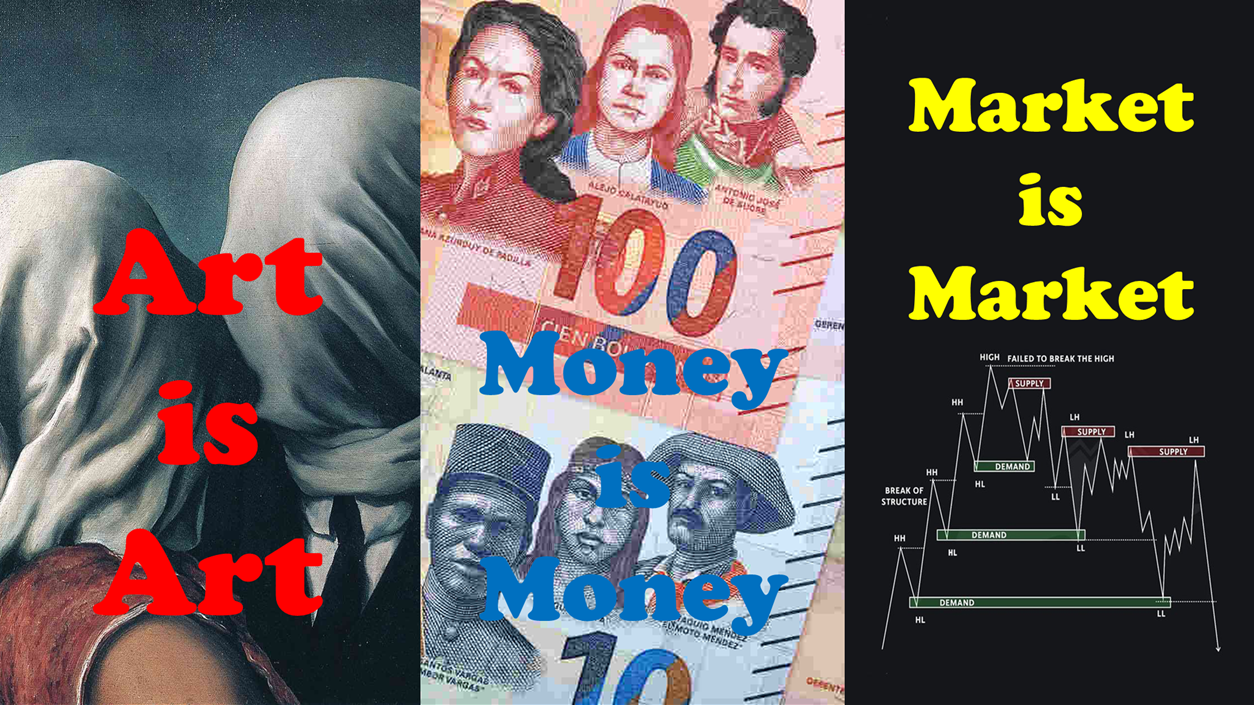

Introduction: What Is Semiotic Capitalism?

In the 21st century, late capitalism has evolved beyond an economy of

production and consumption into a system where symbols and signs dominate

value. Jean Baudrillard called this the “political economy of the sign,” where

the symbolic meaning of things supersedes their material substance. In such a

system, commodities are no longer just physical objects—they are bundles of

signs, socially coded and ideologically charged.

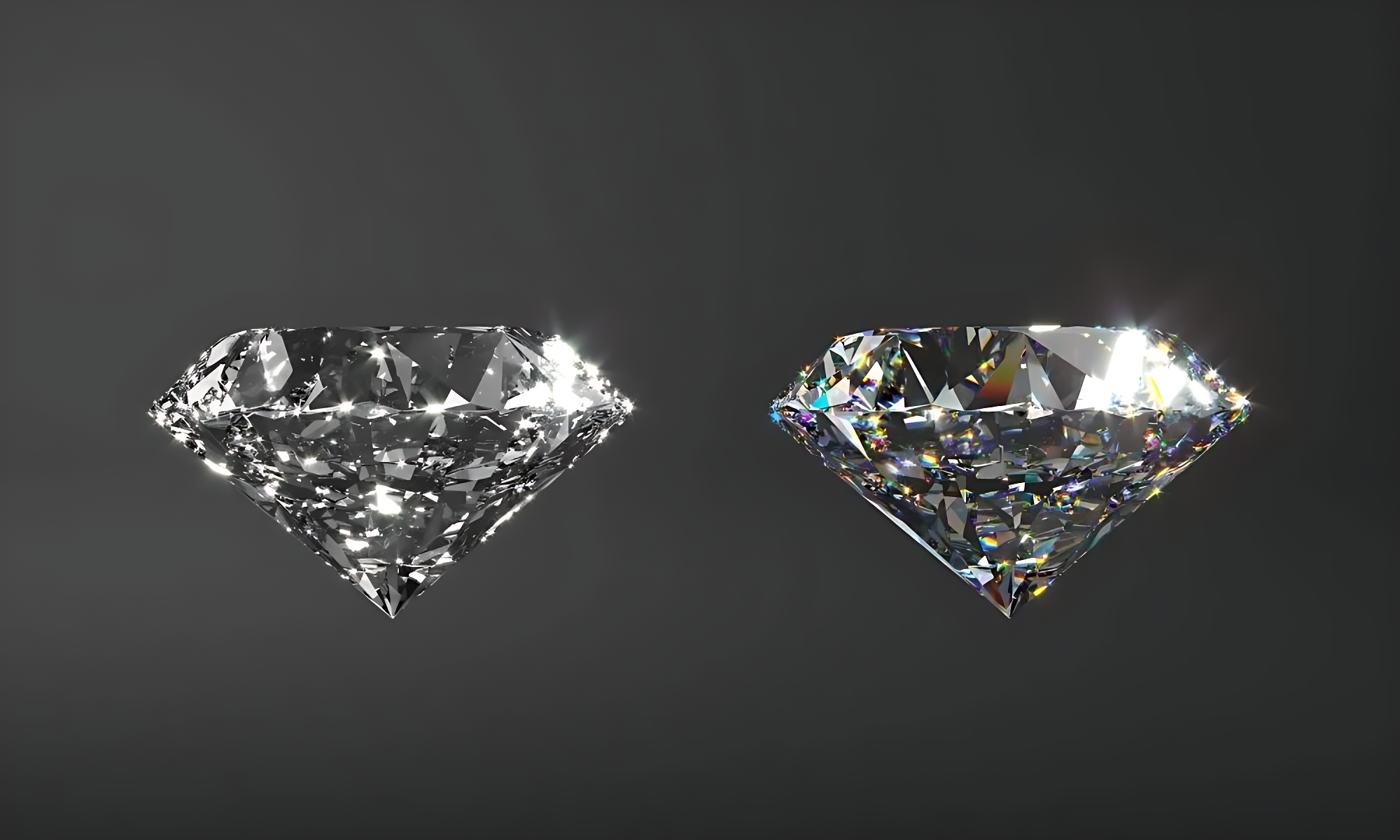

Semiotic capitalism refers to a structure in which value is no longer

determined by utility or labor, but by the symbolic effect and sign-value a

product carries. Nike’s swoosh functions not merely as a checkmark, but as a

symbol of victory and personal narrative; Louis Vuitton’s monogram represents

class distinction rather than function; and Apple’s bitten apple signifies

innovation and emotional resonance more than technological function. These

signs do not just sell products—they organize desire and produce identity. This

symbolic regime extends deeply into the cultural industries, and most

significantly, into the realm of fine art.

Erasing the Real: The Image-Fication of Fine Art

Baudrillard’s age of simulacra has materialized on the walls of museums

and art fairs. Today, artworks no longer serve to represent the real or

generate new meaning; instead, they circulate within chains of signifiers. An

artwork is no longer an autonomous creation but exists as a mediated

image—branded, priced, storied, and socially endorsed via social media metrics.

In this regime, the interiority and reality of art are erased. A painting

becomes a backdrop for selfies rather than a field of material and gesture; a

sculpture functions as a spatial prop rather than an object of form. Artistic

criteria such as sensuous tension, material presence, or contemplative depth

are silenced. Works are judged not by their intrinsic quality, but by their

symbolic capital. Fine art thus loses its autonomy and is subsumed under the

logic of simulation.

The Politics of Desire and the Outsourcing of Art

Maurizio Lazzarato argues that contemporary power operates not through

repression, but through the production of desire. Likewise, art is no longer an

act of autonomous expression but a labor process that reproduces externally

generated desires through signs. Artists no longer ask what they themselves

want to create. Instead, they sense what the market, institutions, or

algorithms desire—and strategize accordingly.

The artistic subject is deconstructed and replaced by a network of

curators, galleries, collectors, and social media algorithms. Artistic

production becomes outsourced labor in service of others' desires. Works

function as brand-positioning assets, not as explorations of concept or

sensation. Their reason for existence is increasingly reduced to their semiotic

utility.

The Collapse of Contemplation: Information and Metrics Rule

Today, audiences no longer experience artworks—they investigate them.

Before standing in front of a piece, they search online, read hashtags, and

verify the artist's CV. In an era where Artnet auction prices say more than a

museum wall label, contemplation gives way to data processing.

The viewer no longer perceives the artwork as a sensuous or conceptual

object, but as quantifiable data. Formal concerns like color, composition, and

narrative matter less than where the work was exhibited, who collected it, and

how its value might appreciate. The viewer becomes not a recipient but a

decoder of signs—guided not by intuition, but by market intelligence.

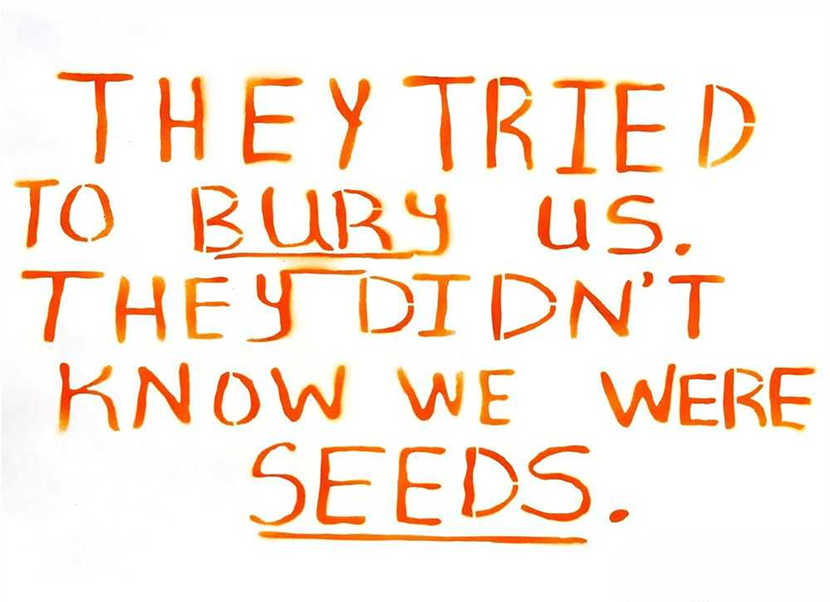

When the ‘Language of Resistance’ Becomes a Product

The most insidious tactic of semiotic capitalism is its ability to

commodify even the language of critique. Works that claim to resist capitalism,

address gender, climate crises, migration, or inequality often function less as

acts of dissent and more as symbolic tokens within curatorial frameworks.

Critique no longer causes discomfort or disruption—it becomes another

aesthetic category labeled “cool” or “urgent.” The transgressive energy of art

is neutralized; the language of dissent is domesticated into the decorative

vocabulary of the system. Fine art no longer serves as a disruptive force, but

as a lubricant that keeps the machinery of the symbolic economy running.

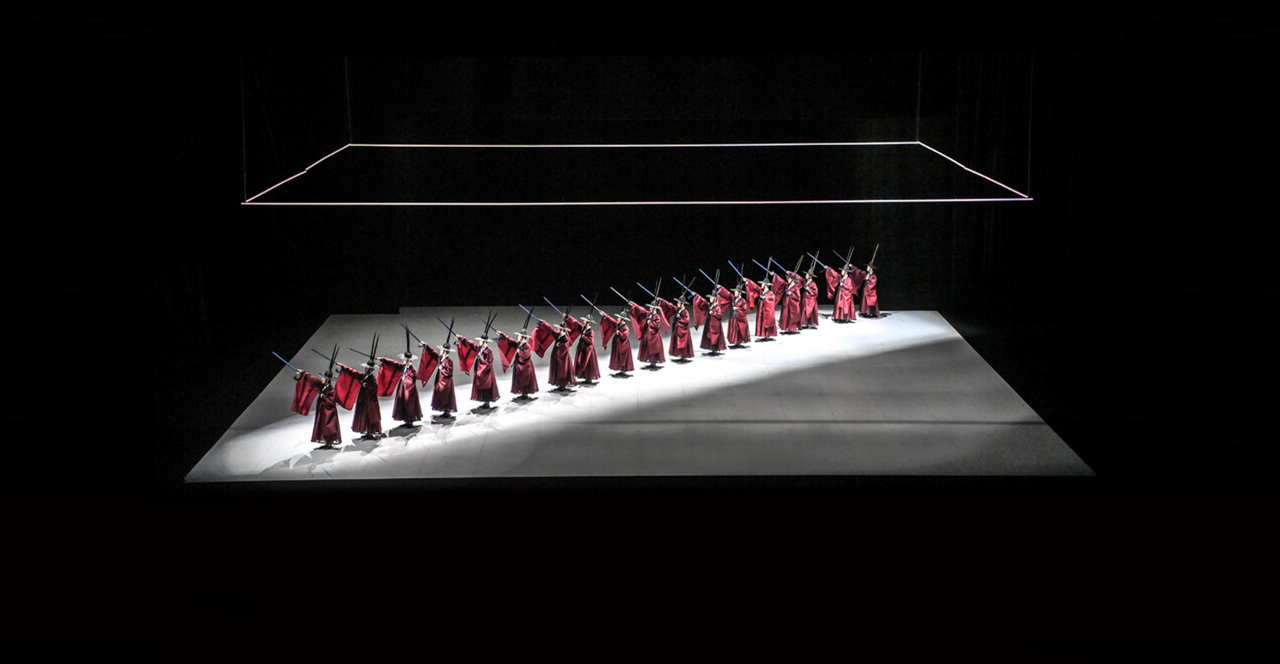

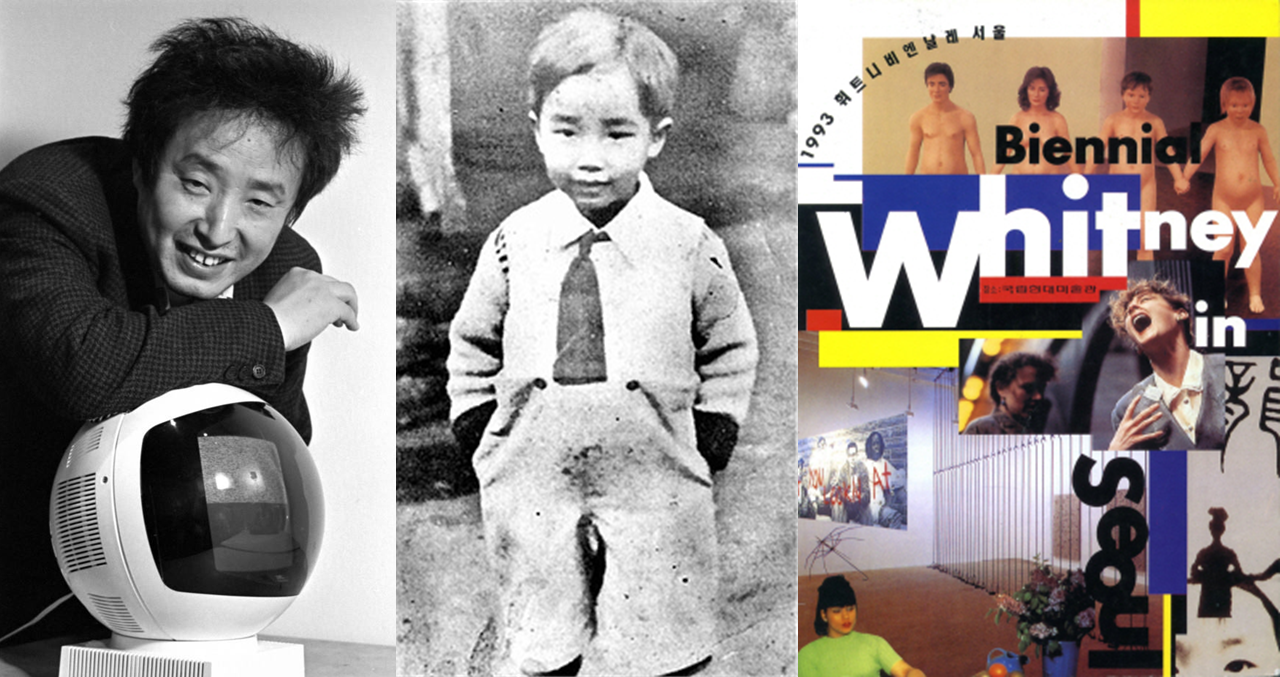

The Institutional Turn: Factories of Sign Production

Museums, biennials, art fairs, and residencies today are not mere sites of

exhibition or production. They are platforms for engineering, curating, and

distributing signs. Curators act less as critical selectors and more as

narrative designers. Exhibitions are conceived as bundled story-driven content.

Art fairs function as exchanges that convert sign-value into monetary

price; museums serve as legitimating systems that institutionalize semiotic

value. In this structure, fine art is not an autonomous zone but a node within

a larger industrial system of symbolic production.

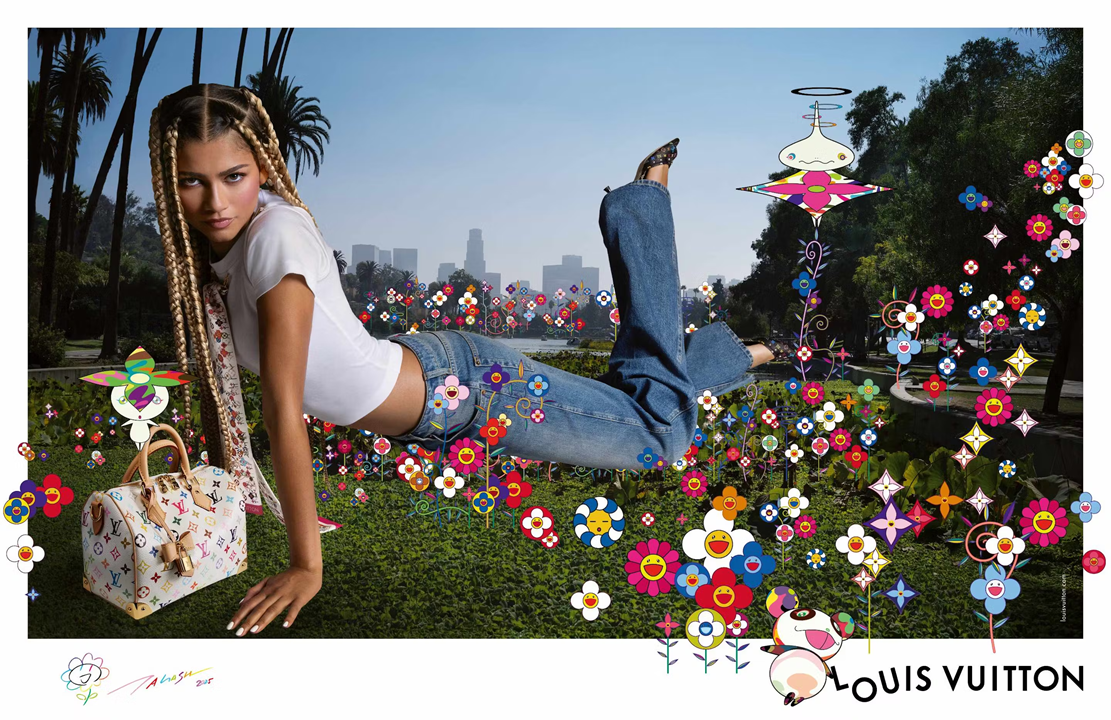

The Artist’s Dilemma: Brand or Creator?

Today, artists are brands before they are creators. Their identity is

formed not through body of work, but through metrics—social media followers,

gallery affiliations, collection records, and commercial partnerships. In this

system, “who made it” matters more than “what was made.” And “who” is no longer

about philosophy or sensibility, but a quantifiable semiotic résumé.

For emerging artists, the pressure is immense. Rather than developing an

original language, they are compelled to master market codes and marketing

strategies. Creation becomes a means of validation, and experimentation gives

way to calculated planning. Art becomes a proof-of-worth exercise in an

algorithmic ecosystem.

How to Escape the Grip of Signs

Semiotic capitalism is not an external force—it operates from within the

art world. The danger lies not simply in market expansion, but in the

uncritical internalization of its logic by artists, institutions, and audiences

alike. This is the art world’s self-dissolution, a surrender of autonomy and

the real.

To resist this structure, fine art must cease to be a reproducer of signs

and become a disruptor. The artist must crack open the language of the market;

the viewer must look beyond the gloss of surface signifiers to ask: what is

real here? Art must return not to image, but to sensation, to thought. It must

once again become a language of the pre-object.

Conclusion: Can Fine Art Stand on the Side of the Real Again?

In the age of semiotic capitalism, fine art is judged not by depth of

meaning, but by surface visibility. The power of thought is reduced to metrics;

the time of art is subordinated to the tempo of markets and algorithms. We are

left with a fundamental question:

What is art? Is it still something that reveals—or has it become something

that merely reflects?

We must return, again and again, to this old, even tired question. For it

is in the repeated asking—and in the struggle to answer—that art may once more

reclaim the real within the empire of signs.

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.