The Myth of Possessive Desire

“Who bought that piece?”

This question often wields more power than the artwork’s intrinsic aesthetics

or philosophy. In today’s art world, the collector is not merely a purchaser

but a powerful actor who structures value and inscribes narrative.

Collecting now stands at the ambivalent

intersection of value accumulation and symbolic representation, exposing the

deep structures of desire and the language of power that underlie the art

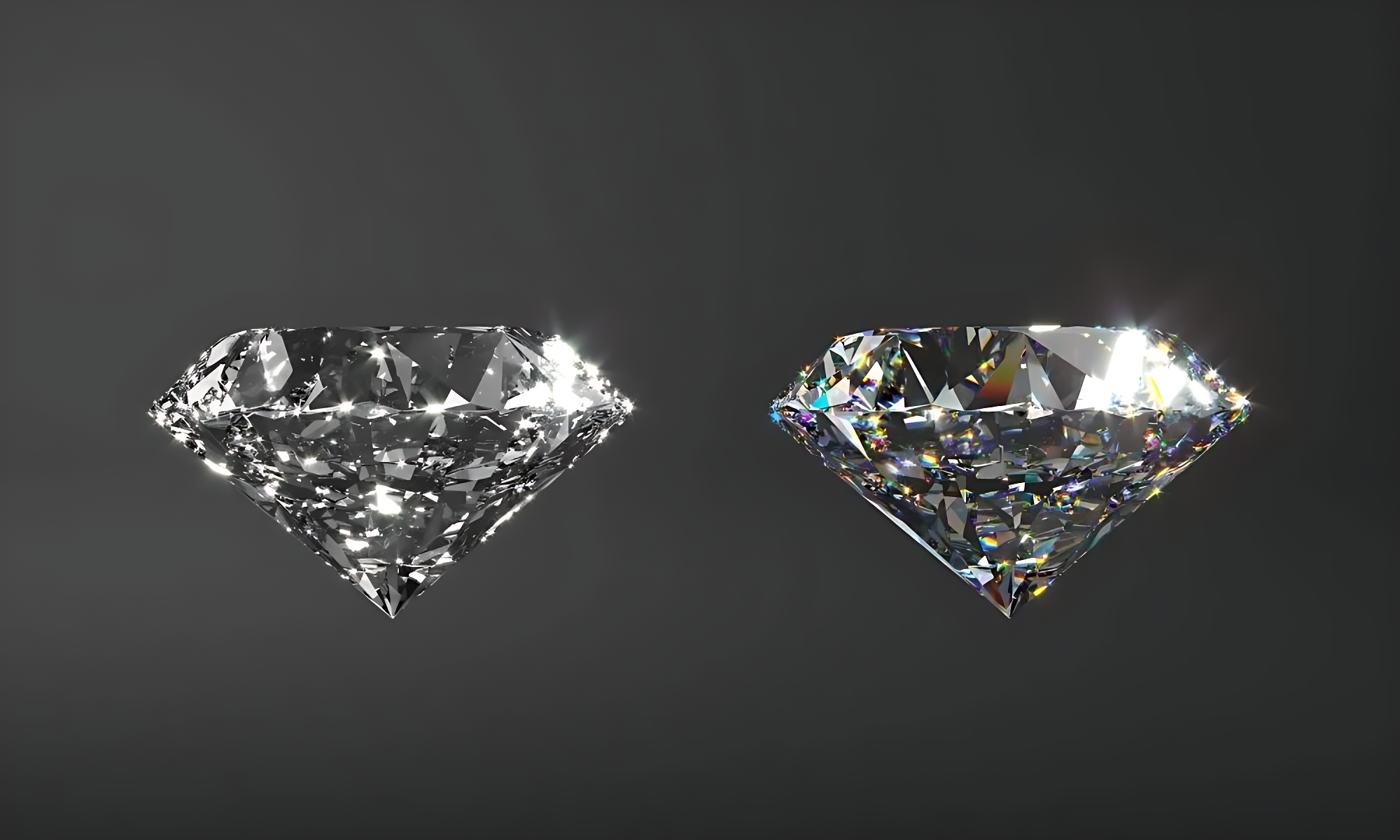

market. In this age, it is no longer the authenticity or artistic integrity of

a work that determines its value, but the context of its ownership and

narrative capital.

Collecting functions not as a discreet

exercise of taste, but as a visualization—and institutionalization—of

capitalist desire.

From the perspective of Deleuze and

Guattari, desire is not a symptom of lack but a productive force. Collecting,

therefore, is not an act of compensating for what is absent, but an assertion

of new orders, new hierarchies. The collector’s gesture is not aesthetic but

systemic—a symbolic return to the center of power through reified art.

From Aesthetic Sensibility to Social

Position

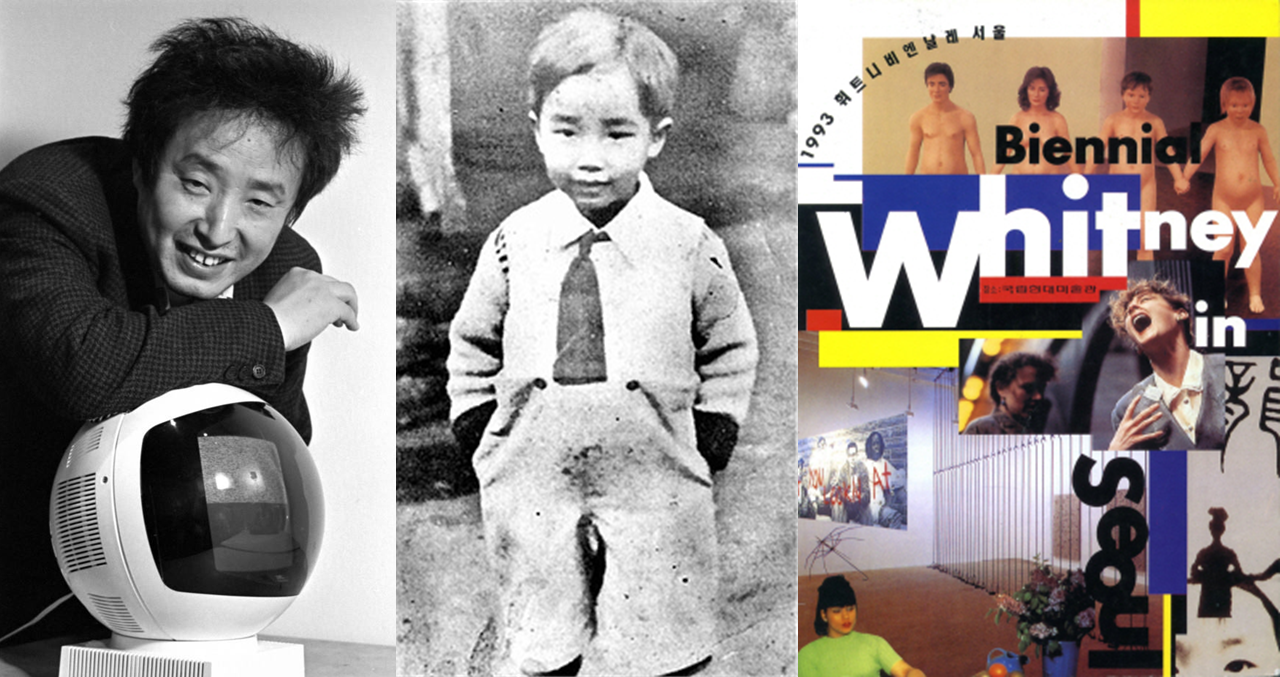

In the Renaissance, aristocrats used art

collections to visually assert their status. While churches and monarchs used

art for symbolic dominance, the bourgeois class later appropriated it as

cultural capital. In the mid-20th century, figures like Peggy Guggenheim

advanced a new model of “patron-collector” by discovering artists such as

Jackson Pollock, while Charles Saatchi exemplified the “market-maker,”

strategically launching the YBAs (Young British Artists) into the commercial

and critical spotlight.

This shift was not about mere

connoisseurship but about strategically positioning oneself as an arbiter of

value. In Korea, from the 1990s onward, early collectors established themselves

through alliances with public institutions, museums, and galleries—becoming

monopolists of taste. They were not just viewers, but intermediaries shaping

both artists and institutions.

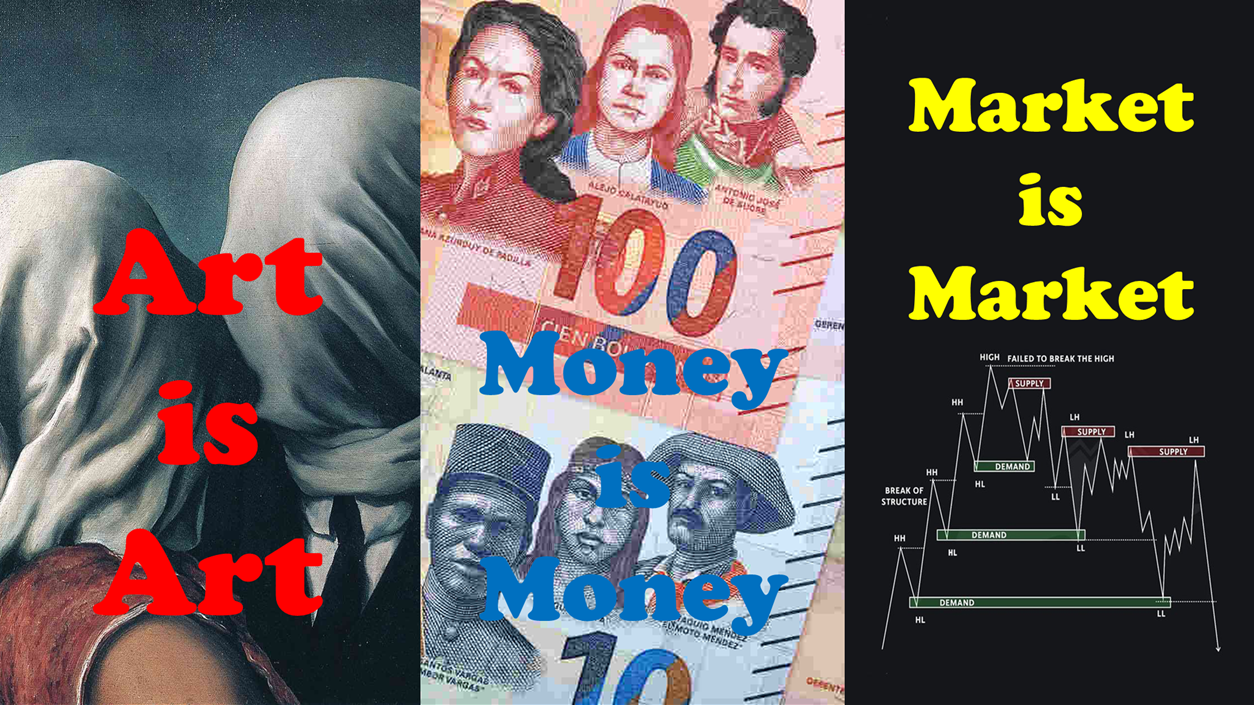

Thus, art became less a matter of

appreciation and more a form of symbolic asset. Collection is now a visual

strategy that reveals one’s position within the hierarchy of capital and

culture.

The Collector as the Market’s Eye

Today’s collectors no longer operate based

on personal taste alone. Their gaze is connected to a complex

network—institutions, media, technology, and finance. Art is increasingly

evaluated based on these five questions:

• Who already owns it? (First-tier

collector status)

• Which institutions have acquired it? (Museum or public collection presence)

• What is its resale potential? (Auction record, liquidity)

• What social message does it carry? (Gender, politics, identity)

• Is it currently trending? (Media visibility, social engagement)

For example, the market value of artists

like Lee Ufan or Yun Hyong-keun—or even emerging artists—rises rapidly through

the triangulated collaboration of collectors, auction houses, and galleries. In

this mechanism, the collector becomes both the market’s eye and the voice of

its narrative.

The market no longer privileges artistic

vision but ownership. Who possesses the work becomes its brand. Thus, artworks

devolve into symbolic markers, cultural commodities, and collectors emerge as

the dominant evaluators of artistic worth.

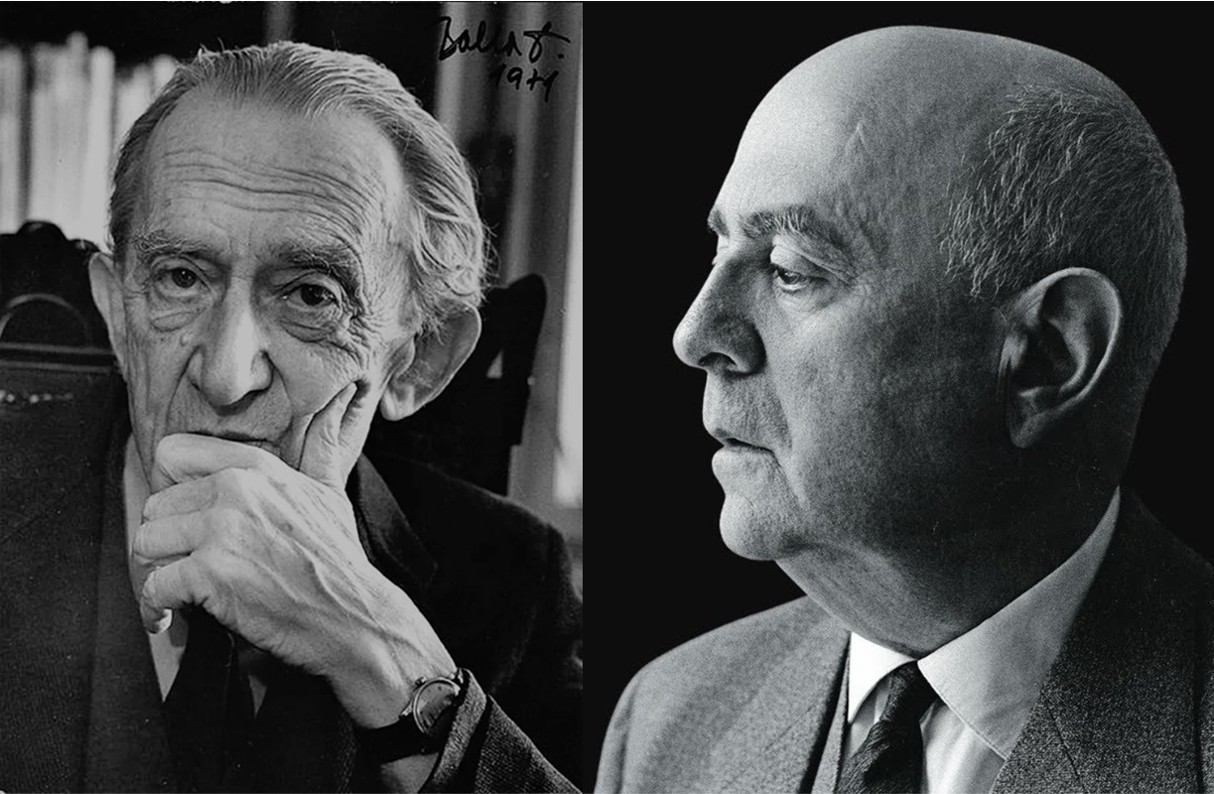

Art as a Social Signifier — After Bourdieu

Pierre Bourdieu, in Distinction,

argued that cultural capital and taste reproduce class structures. Applied to

the Korean art market, the act of collecting high-value art is less about

aesthetic pleasure and more about asserting or elevating one’s social standing.

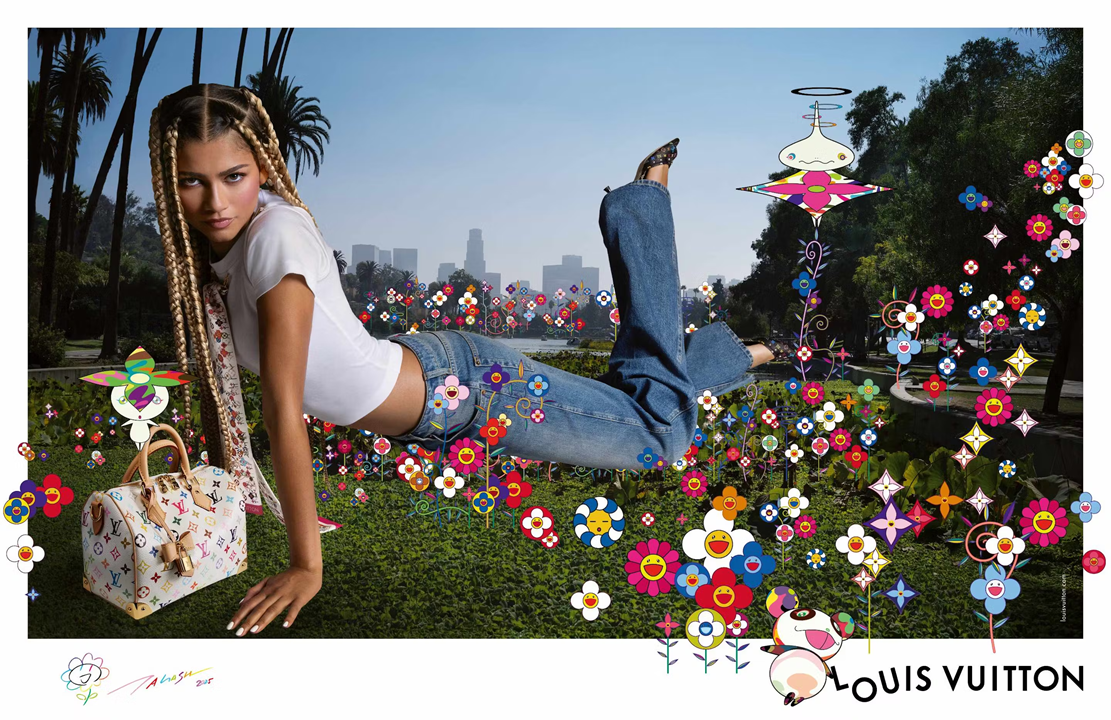

When younger collectors say they’re “buying

art instead of luxury cars,” we must read this not as diversification of assets

but as symbolic redefinition of identity. Artworks are not understood per se

but function as linguistic tokens reserved for those “qualified” to comprehend

them. Thus, art becomes a language of exclusion—closed symbolic capital that

encodes class.

Moreover, collecting has evolved to consume

identities—gender, queerness, postcoloniality—as new currencies. A male

collector who buys feminist paintings acquires a “progressive” aesthetic

identity. A global collector of Korean diasporic work performs a cosmopolitan

sensitivity. In every case, it is no longer a matter of what is seen,

but what is owned.

Buying Narratives, Constructing Mythologies

Today’s collectors don’t merely acquire

objects—they purchase narratives: political contexts, identity discourses, and

social messages. The feeling of having made a “righteous acquisition” offers

both ethical justification and cultural capital.

For instance, works on refugee crises,

feminist installations, or paintings emphasizing regional specificity are often

valued more for their political gravity than for their formal innovation.

Collectors, by acquiring them, insert themselves as agents in ongoing cultural

discourses.

A painting armed with narrative becomes more than a collectible—it becomes a

raw material for self-representation.

A male collector of feminist art performs

progressive refinement. A European buyer of Korean diaspora art appears

globally sensitive. These dynamics create new symbolic hierarchies. This is the

art of late capitalism: no longer an expression of interior truth, but of

brandable discourse, aestheticized identity, and consumable narrative. Art

becomes reified—again.

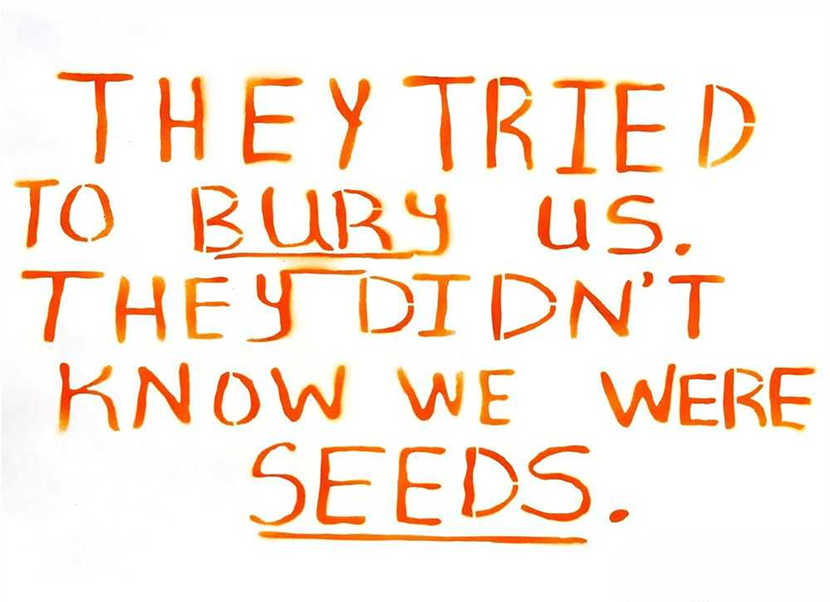

Conclusion: Collusion or Deconstruction?

Collectors are no longer passive buyers.

They are authors of value, co-architects of narrative. What matters is not the

work’s form or experimentation, but its owner and its place in a larger

symbolic economy. This system is fueled by capitalism’s “fantasy of possession”

and its seamless integration with symbolic power.

How far can art still function as art?

When the artwork is no longer a subject of interpretation but a token of social

validation, how can its aesthetic integrity survive? When art holds hands with

capital, does it surrender its autonomy—or paradoxically, gain a broader stage?

We must now ask:

Do you see the artwork—or do you wish to be

seen through it?

This question is no longer about perception

but about the existential conditions of art in a reified age. In this era,

collecting is not an extension of taste but a manifestation of power. And

power, when left uninterrogated, will be endlessly reproduced through the

machinery of capital.

Fine art, grounded in human introspection,

faces a critical juncture. If it fails to deconstruct itself, it risks being

entirely overwritten by the language of capital.

The answer to this dilemma may very well define the moral urgency and

authenticity that artists must embrace in the age of reification.

References

• Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction:

A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, 1979

• Sarah Thornton, Seven

Days in the Art World, 2008

• Olav Velthuis, Talking

Prices, 2005

• Peggy Guggenheim, Confessions

of an Art Addict, 1946

• Charles Saatchi interviews, The

Guardian, 2009

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.