MGM Discoveries Art Prize

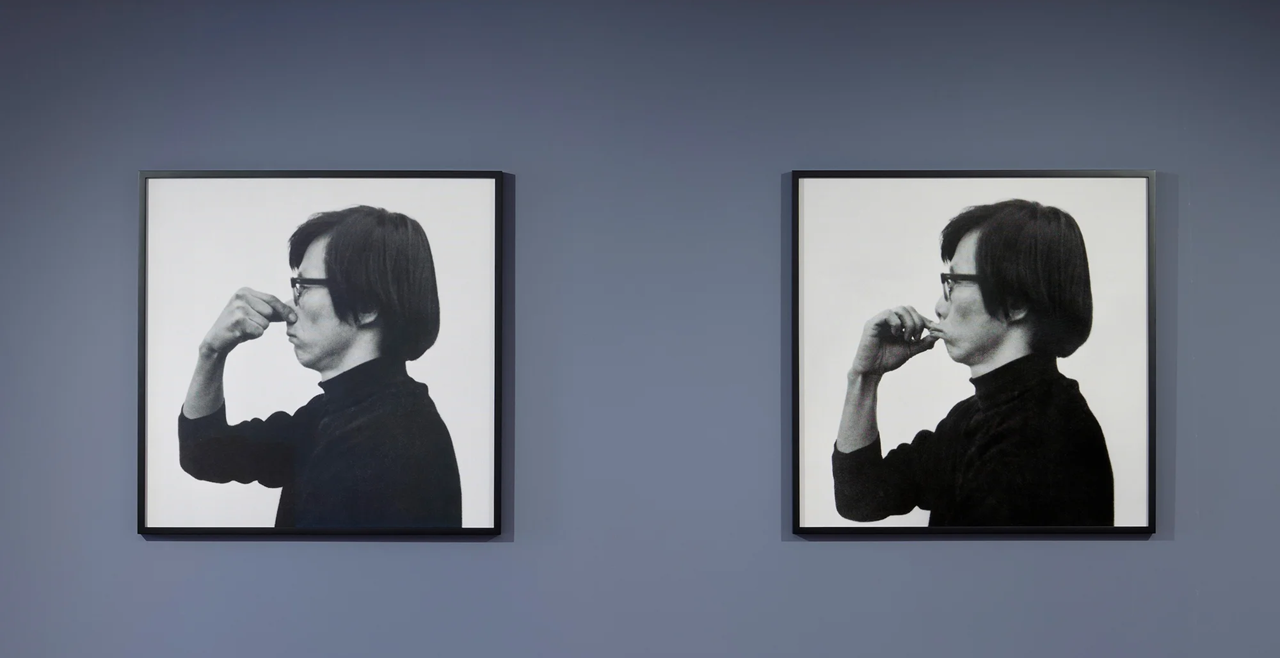

Winner : Shin Min / Courtesy of Art Basel

MGM Discoveries Art Prize

Winner : Shin Min / Courtesy of Art BaselKorean artist Shin Min (b. 1985) has been awarded the

first-ever MGM Discoveries Art Prize at Art Basel Hong Kong 2025,

earning international attention for her poignant and politically charged work.

Represented by P21 Gallery in the fair’s Discoveries section,

Shin was selected as the sole winner among three shortlisted artists, receiving

a $50,000 prize and an upcoming solo exhibition opportunity in

Macau.

Installation view of Shin Min's Usual Suspect at Art Basel Hong Kong 2025 / Courtesy of Art Basel Hong Kong

The jury praised Shin’s work as “a portrait of women

enduring within a rigid social structure—an homage to their perseverance.” Art

Basel also listed her work among the “8 Must-See Works” at the 2025

edition.

Paper, Anger, and Solidarity:

Sculpting Resistance

Drawing on her own experiences working in fast-food chains

and cafés to support herself, Shin Min explores how female service workers,

often required to wear hairnets, are monitored, objectified, and

systemically marginalized under capitalist structures.

Her materials—paper, clay, pencil, and crayon—may seem soft and

ephemeral, but they bear the weight of rage, exhaustion, and resilience. Shin’s

sculptures are not mere forms; they are living narratives.

«Genre Allegory – Sculptural», 2018, Total Museum of Art

Art Rooted in Experience: Faces

of Invisible Labor

Her ongoing series ‘Usual Suspect’ takes its name

from the way service workers are scrutinized through CCTV footage to identify

who “dropped a hair” when customer complaints arise.

«Genre Allegory – Sculptural», 2018, Total Museum of Art

One

notable work from this series, titled Yuck! There’s Hair in My Food,

transforms that absurd yet disturbingly real scenario into a striking

installation.

Each

sculpture is crafted by layering more than ten sheets of oiled paper over a

clay form, then drawn and colored with crayon. Their exaggerated

features—furrowed brows, bulging eyes, open mouths—defy the forced smiles and

submissiveness expected in the service industry. Shin’s figures embody

unapologetic anger.

«Special Exhibition for the

10th Anniversary of Lee So-sun – Voice», 2021, Jeon Tae-il Memorial Hall

«Special Exhibition for the

10th Anniversary of Lee So-sun – Voice», 2021, Jeon Tae-il Memorial Hall

Capitalism Felt Through the Body,

Imprinted on Paper

While working at McDonald’s, Shin was struck by the sheer

volume of discarded French fry sacks, which she came to see as metaphors

for disposable labor. Her 2014 sculpture Part-Time Worker in

Downward Dog Pose uses actual McDonald’s fry bags wrapped over

figures wearing hand-drawn uniforms. “I used the residue of poverty to depict

poverty,” she explains.

«Part-Time Worker in Downward

Dog Pose» Exhibition View, 2014 / Photo: Shin Min, Courtesy of Women’s Economic

Daily

«Part-Time Worker in Downward

Dog Pose» Exhibition View, 2014 / Photo: Shin Min, Courtesy of Women’s Economic

DailyHer use of the black satin-ribbon hairnet, a ubiquitous symbol of Korean service workers, recurs throughout her practice. In works like ‘Our Prayer’, the hairnet-wearing figures no longer appear submissive. Their piercing eyes and tense faces transform them into avatars of collective resistance.

«Paper Mirror», Exhibition

View, 2023 / Seongbuk Children’s Museum of Art

«Paper Mirror», Exhibition

View, 2023 / Seongbuk Children’s Museum of Art

Sculptures as Talismans: Paper

Rituals and Prayers

Shin embeds handwritten prayers into her

sculptures—messages wishing protection for viewers or loved ones. Her creative

process resembles a spiritual ritual: paper is layered, text is repeated, and

the resulting face reflects accumulated emotion.

“I don’t just make sculptures—I make paper talismans,” she

says.

At Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), her installation The

Future Reflected in My Heart allowed viewers to write their own

wishes and attach them directly to the large bust, encouraging physical and

emotional participation. For Shin, sculptures should not be fossilized objects

but living altars for collective hope and catharsis.

Hey CCTV, Watch Us Dance—Reclaiming Surveillance Through Play

In her 2024 exhibition 《The Art of the Attention-Seeker》 at the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, Shin

presented Hey CCTV, Watch Us Dance, a bold reimagining of surveillance culture.

Instead of being passively observed, her figures face the cameras and perform,

turning surveillance into self-expression. For Shin, being a “performative

attention-seeker” is a strategic act of resistance—a way to amplify

marginalized voices and provoke public dialogue.

Exhibition View of 《The Art of the Attention-Seeker》, 2024 / Busan Museum of Contemporary Art

Her work Let’s Take a Selfie Together❤️ imagines teenagers posing for a group photo that could be seen as cringe-worthy, defiant, or revolutionary—all at once. She frames SNS activity as contemporary solidarity, where likes and tags become gestures of mutual support.

Hey CCTV, Watch Us

Dance›, 2024, Wall Drawing, 8220 × 4500 cm

Hey CCTV, Watch Us

Dance›, 2024, Wall Drawing, 8220 × 4500 cm

Cute, Fierce, and Alive: Shin

Min’s Sculptural Language

Shin openly describes herself as “a social media addict

with a bloated ego.” Her aesthetic may appear playful or even

cartoonish—“like something made in a high school art class,” she says—but it is

underpinned by sharp political critique and emotional intensity. Her use of

paper is intentional: fragile and ever-changing, it mirrors the precarity of

life under capitalism.

«Make a Wish», 2024, Seoul

Museum of Art, Buk-Seoul Branch

«Make a Wish», 2024, Seoul

Museum of Art, Buk-Seoul BranchHer

recent projects, such as «Make a Wish» (SeMA, 2024), invite tactile

interaction—encouraging visitors to touch, write on, and complete the artwork

themselves. “Even if it gets damaged,” she says, “I want the work to live and

breathe with people.”

Paper

Figures as Social Mirrors

«Shackles and Nose Rings»,

2019, OCI Museum of Art

«Shackles and Nose Rings»,

2019, OCI Museum of ArtShin is currently expanding her scope to explore the

biological roots of war and gender, questioning the structural foundations

of violence and the place of the female body in that history. Her work

increasingly adopts a macro perspective, but her core remains the same: lived reality, feminist rage, and a yearning for transformation.

Her sculptures are not just objects; they are portraits

of the unheard, reflections of society’s blind spots, and amplifiers of

suppressed voices.

Open Studio Day in Chuncheon,

Artist Shin Min / Photo: Kim Ha-young, Courtesy of Women’s Economic Daily

Open Studio Day in Chuncheon,

Artist Shin Min / Photo: Kim Ha-young, Courtesy of Women’s Economic DailyShin Min (@fatshinmin) has participated in numerous major exhibitions, including 《The Art of the Attention-Seeker》 (Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, 2024), 《Make a Wish》 (SeMA, 2024), 《Paper Mirror》 (2023), 《Se-Mi》 (2022), 《Sculptural Impulse》 (SeMA, 2022), 《Voice》 (Jeon Tae-il Memorial Hall,

2021), 《Shackles and Nose Rings》 (OCI Museum, 2019), and 《Genre Allegory

– Sculptural》 (Total Museum of Contemporary Art,

2018).