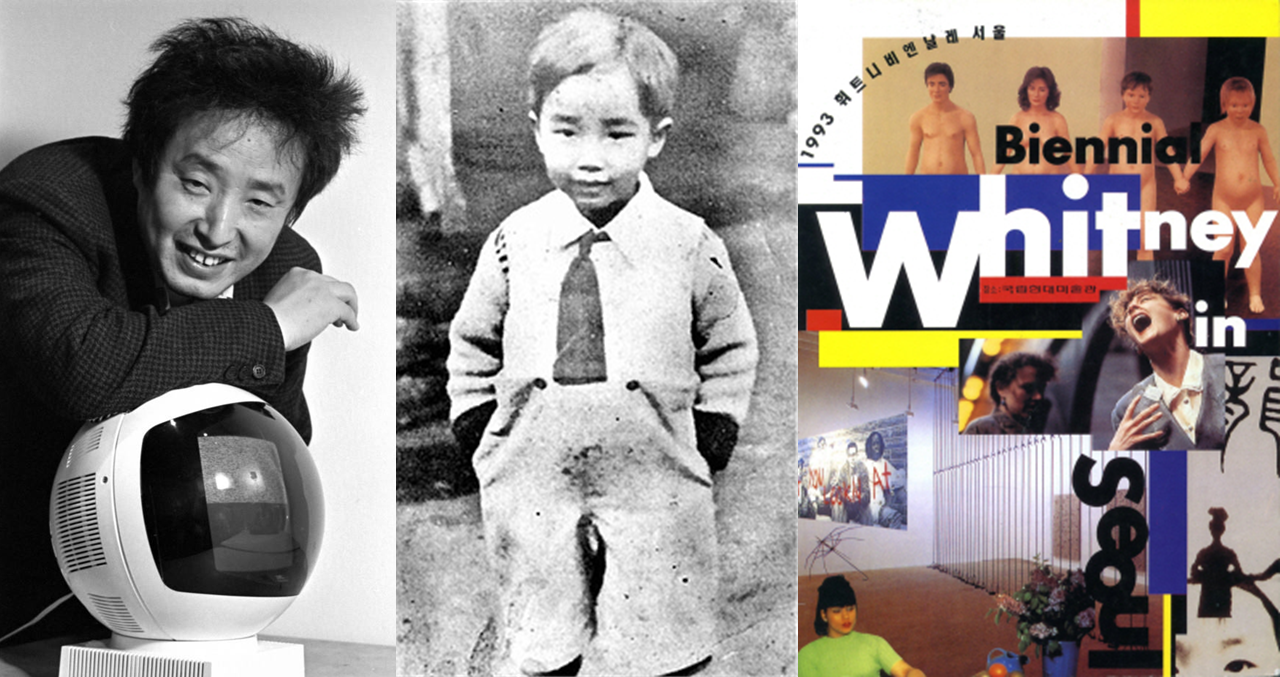

In 2025, two of Korea’s most prominent art figures have

returned to lead major cultural institutions. Yoo Hong-jun, former

Administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration, has been appointed

Director of the National Museum of Korea, while Yoon Bum-mo, former Director of

the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), has taken the helm

as the new CEO of the Gwangju Biennale. Both are respected art historians,

critics, and curators with long careers in the field. Their return has inspired

expectations of “stability” and “experience.”

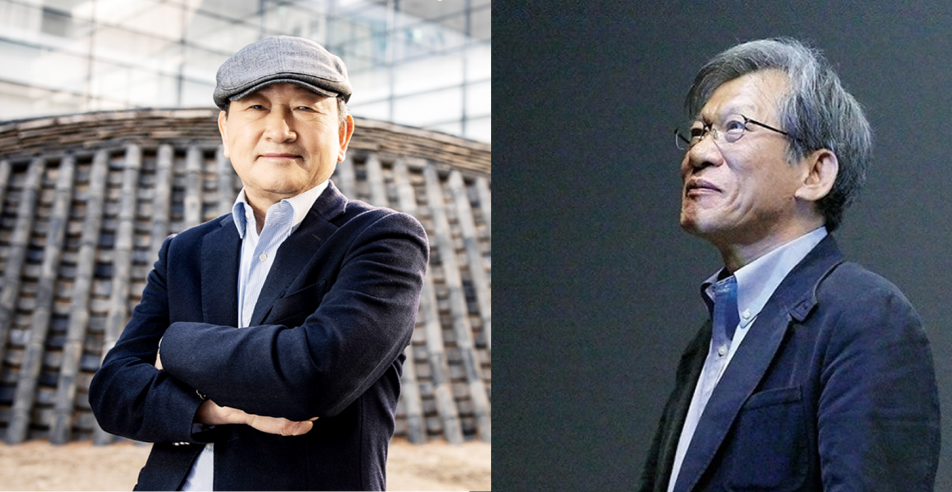

Yoo Hong-jun, new Director of the National Museum of Korea

Yoon Bum-mo, new CEO of the Gwangju Biennale

Yet today’s cultural landscape faces fundamentally

different challenges and opportunities than in decades past. In this context,

their return must not be a simple replay of the past, but a critical inflection

point—a chance to restructure systems and strategies with the benefit of

accumulated experience.

Yoo Hong-jun’s “Overseas Touring Exhibitions”

At his inaugural press conference, Director Yoo

announced plans to promote overseas touring exhibitions featuring artifacts and

curated content from the National Museum of Korea. This proposal continues the

cultural diplomacy strategy he championed during his tenure at the Cultural

Heritage Administration. However, the cultural dynamics of the 2020s require a

new set of tools and logic.

Exterior view of the National Museum of Korea

First, cultural

globalization today is not about “sending” heritage abroad, but about making

Korea a destination that people around the world seek out. BTS, Squid

Game, and global K-drama hits on Netflix have already transformed

Korea into a cultural pilgrimage site. By contrast, the National Museum of

Korea remains far behind this trend.

Second, touring

exhibitions are expensive and often inefficient. Tens of billions of won are

poured into transportation, insurance, installation, and marketing, but many of

these exhibitions yield only short-term attention and a few commemorative

photographs. One example is the large-scale Korean cultural exhibition held in

France during the 2017 “Korea–France Year of Cultural Exchange,” which drew

fewer visitors than expected.

Third, instead of

focusing on exporting exhibitions, it is far more urgent to make the museum

itself a compelling global space worth visiting. In the first half of 2024, the

National Museum of Korea welcomed 94,951 international visitors,

accounting for only 6.1% of its total 1.55 million visitors during that

period. While this marked a 34.5% increase over the same period in 2023, the

share of foreign visitors remains low—between 5 and 7% of an annual audience

that reached 3.78 million. Despite its status as Asia’s largest museum, the

institution still falls short of international standards in multilingual

guidance, online archives, accessibility information, and global digital

services.

It is time to shift the museum’s resources from

“exporting exhibitions” to building a destination-oriented ecosystem.

The future of cultural globalization lies not in movement but in becoming a

destination.

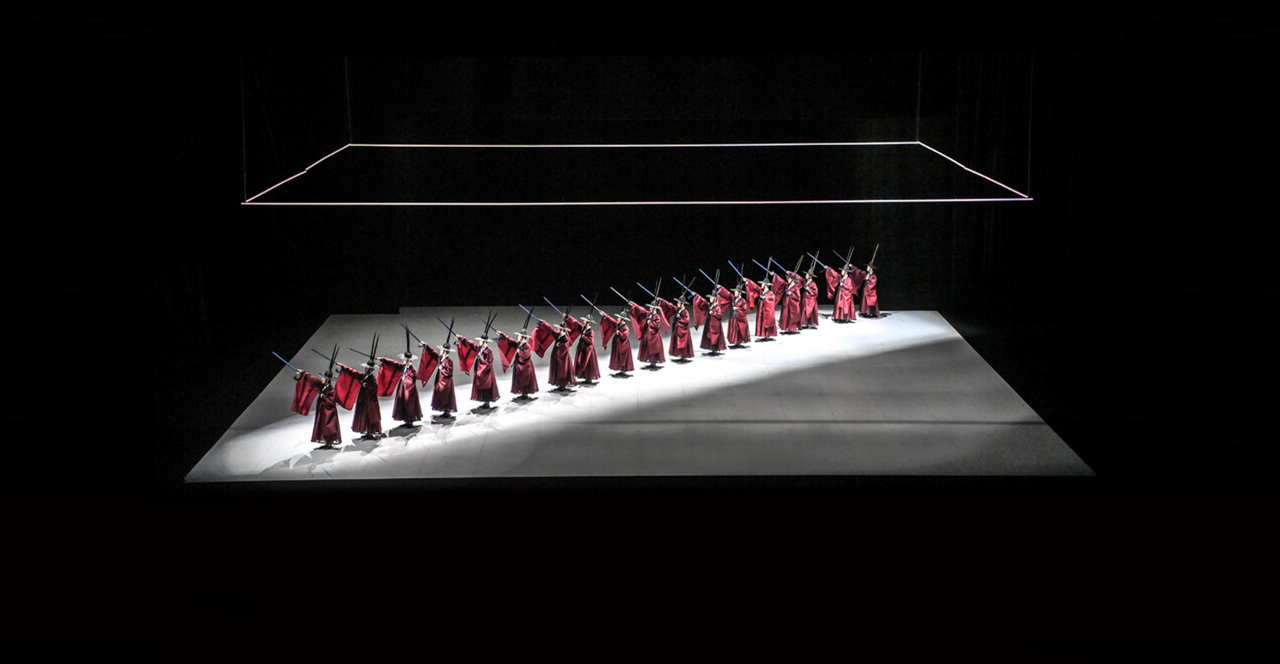

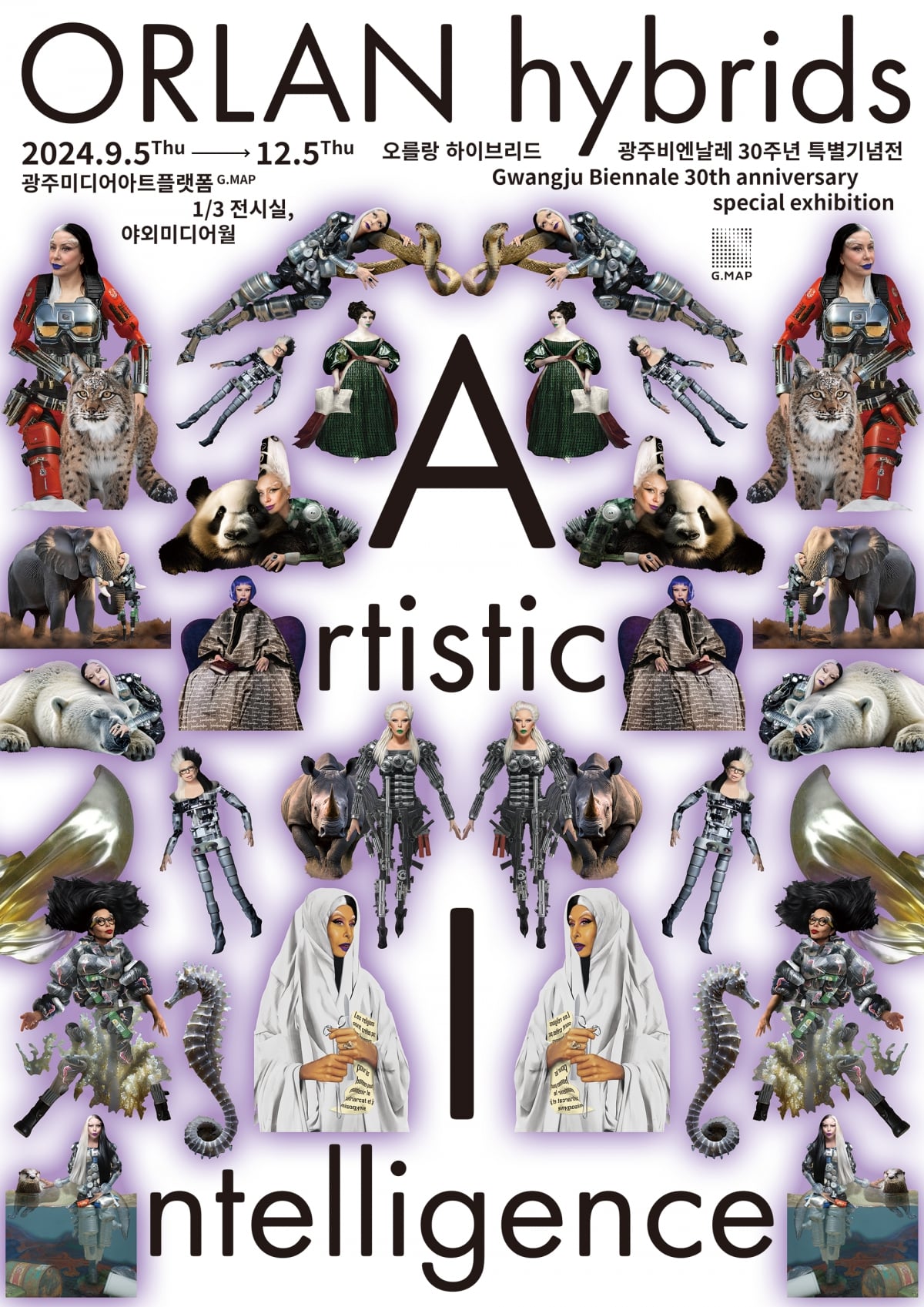

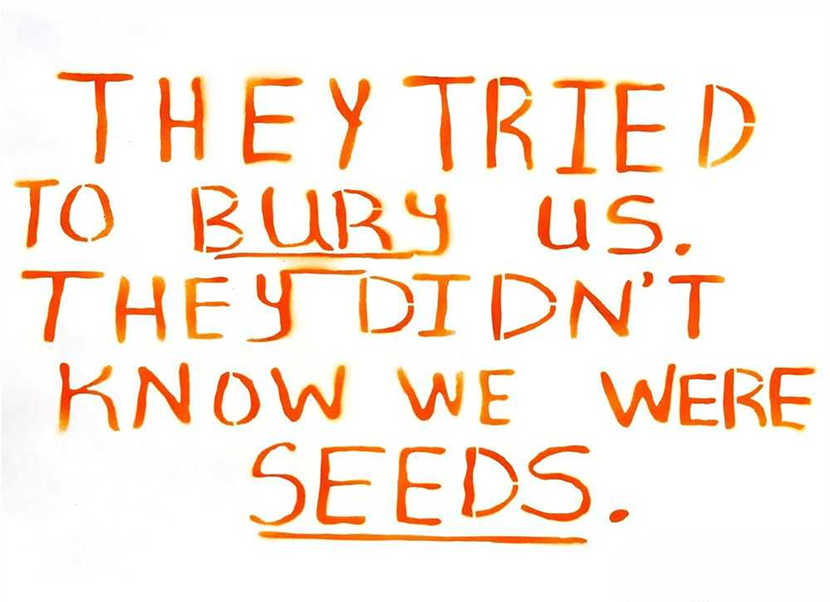

Gwangju Biennale: A Biennale Without an Archive Is a

Museum Without a Collection

Yoon Bum-mo has been involved with the Gwangju Biennale

since its inception. He curated the 20th anniversary special exhibition in 2015

and has stated his intention to “artistically elevate the Gwangju spirit”

during his new term. But the problem today is not one of “spirit”—it is one of record.

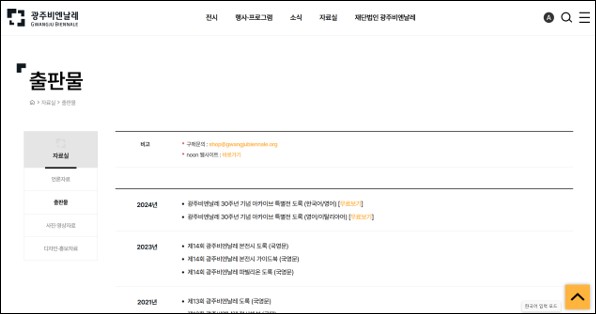

Screenshot of the Gwangju Biennale website

The archive section of the official site is severely underdeveloped for an event claiming to represent Korea’s leading biennale. While the 2024 exhibition catalog is freely accessible, most materials from previous editions are difficult or impossible to find.

Launched in 1995 as Asia’s first international

biennale, the Gwangju Biennale now has a 30-year history. Yet, a proper archive

system remains virtually nonexistent.

Key materials such as past editions’ artistic

directors, themes, artist lists, floorplans, installation views, catalogs,

critical essays, press kits, and photo documentation are not searchable through

the official website or any unified portal. Among the 14 main and special

exhibitions held between 1995 and 2023, many are entirely inaccessible online,

with broken links and missing PDFs. Existing records are fragmented and

inconsistent, falling far short of what researchers, journalists, and curators

need to access and study.

This is not merely an issue of negligence—it is a structural

threat to the identity and sustainability of the biennale itself.

Global biennials like Venice, Documenta, and Shanghai

have already institutionalized their exhibition archives. These archives,

available through their official websites, serve as foundational databases for

future research and curatorial development.

For the Gwangju Biennale to reclaim international

relevance, it must prioritize building a comprehensive, digital, and

structured archive system.

First, it must develop an indexed digital archive

including artist rosters, curatorial proposals, floorplans, media coverage,

video records, and official documentation.

Second, the archive should be multilingual—especially

English-accessible—and offer layered storage of critical writings and scholarly

publications.

Third, it should evolve into a research platform,

enabling data-driven curatorial strategies and facilitating collaboration with

academia.

Without such an archive ecosystem, the “Gwangju spirit”

risks becoming nothing more than a slogan.

Experience Is an Asset, But It’s Not Enough

Yoo Hong-jun’s 『My Exploration of Cultural Heritage』

introduced cultural appreciation to a wide audience. Yoon Bum-mo is known for

translating the trauma of 1980s Gwangju into curatorial language. But the

demands of today’s cultural institutions go far beyond interpretation or

connoisseurship.

What is now required are leadership frameworks that

embrace organizational governance, digital innovation, global networking,

ESG awareness, and public accountability.

Leading institutions around the world have already

adapted.

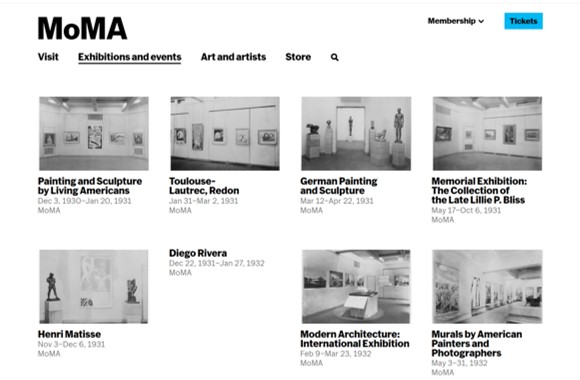

Tate Modern uses AI to analyze visitor flows and optimize programming. MoMA has expanded its curatorial scope to include digital archiving and NFT

acquisition.

Screenshot from MoMA’s digital archive platform

In contrast, many Korean institutions remain stuck in a

revolving door of cultural gatekeeping and legacy appointments. While the

return of seasoned figures may offer stability, it must not signal a regression

into outdated models. Their true task is to convert experience into

foresight—and to use it to reimagine institutional futures.

Globalizing Korean Art Requires Better Systems, Not

More Shows

What Korean art needs to reach the world is not more

touring exhibitions. It needs a systemic cultural infrastructure:

reliable content production mechanisms, transparent operations, sustainable

international collaborations, and the coexistence of scholarship and critical

discourse.

The global art world is no longer content to merely

“see Korea”—it now seeks to learn from Korea. To meet this expectation,

Korean museums and biennales must rebuild themselves from the inside

out—according to global standards.

What matters now is not how many exhibitions we

produce, but what we leave behind—and how we structure it.

Now is the time for these “old boys” to redefine the

meaning of their return—not as restoration, but as transformation. Their true

legacy will not lie in repeating the past, but in leading the structural

reinvention of Korea’s cultural institutions for the generations to come.