The Beginning of

Institutional Photography in Korea

On May 29, 2025, the

Seoul Museum of Photography (Photography Seoul Museum of Art) opens its

doors in Chang-dong, Dobong-gu, Seoul. As the first public art museum in Korea

dedicated entirely to the photographic medium, this institution is not merely

another museum opening—it is a historic milestone.

It signifies a

structural turning point for the many photographers in Korea who have continued

their creative practices despite the longstanding marginalization of

photography within the country’s contemporary art ecosystem.

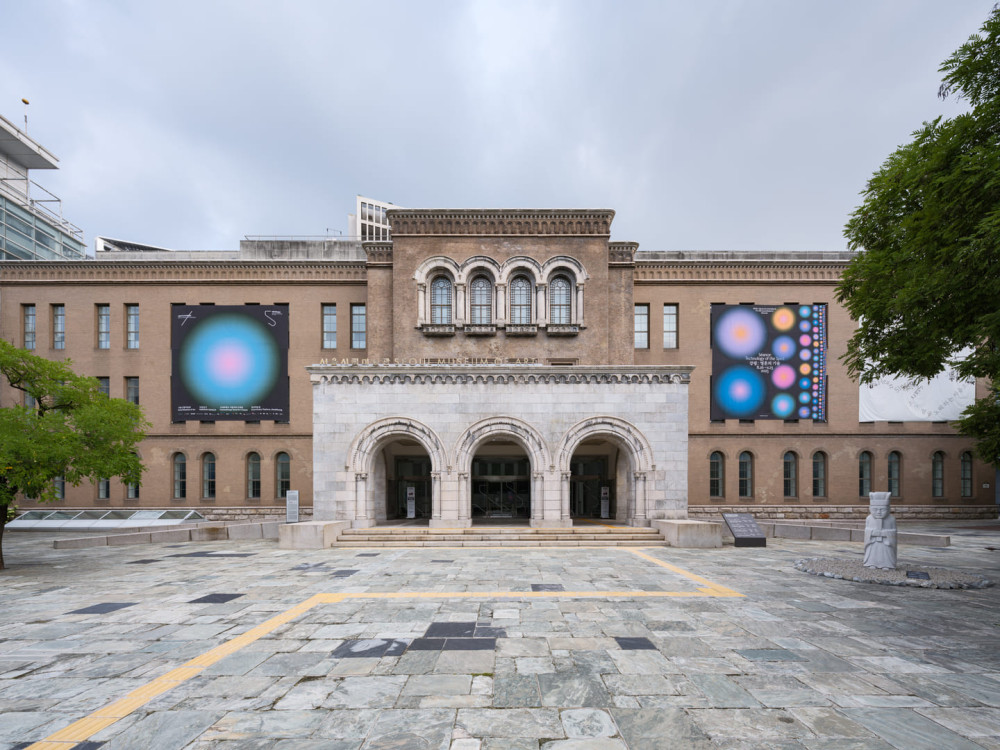

Seoul Museum of Photography, Exterior View / Photo: Jeong Jihyeon, Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art

Seoul Museum of Photography, Exterior View / Photo: Jeong Jihyeon, Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art

Why

Has Korean Contemporary Photography Lagged Behind?

Within the field of

Korean contemporary art, photography has long occupied an ambiguous position.

Compared to painting, sculpture, installation, and video, it has received less

institutional attention, lower market valuation, and limited academic or critical

discourse.

The career path for

photography graduates seeking to become full-time artists has remained severely

restricted. Archiving, conservation, research, and distribution systems for

photography have been underdeveloped or nonexistent. Photographic works make up

only a fraction of public museum collections, and in major open calls,

residencies, and art fairs, photography is rarely treated as a central medium.

This is not merely

the result of aesthetic misunderstanding or market preferences, but of a

structural and institutional failure to recognize photography as an art form.

Ironically, in today’s image-saturated visual culture, photography remains the

most immediate and incisive medium for capturing the spirit of our times.

Seoul

and New York: Two Approaches to Institutional Photography

The launch of the

Seoul Museum of Photography is a direct response to these systemic

deficiencies. More than just a space for exhibitions, it represents a move

toward the institutionalization of photography and the creation of a

formal platform for public discourse.

ICP(International Center of Photography), New York / Image: e-flux

In this regard, the

International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York offers a meaningful

international reference point. Founded in 1974 by Cornell Capa, former

director of Magnum Photos, the ICP emerged with the ethos of “Concerned

Photography”—a philosophy that regards photography as both documentary and

artistic, engaged with the social and political urgencies of its time.

Today, ICP functions

as a comprehensive institution encompassing exhibitions, education, archiving,

publishing, and research. With more than 600 major exhibitions to its name, it

has played a decisive role in shaping the landscape of contemporary photography.

From Diane Arbus and James Nachtwey to Nan Goldin and Sebastião Salgado, it has

hosted artists who push the boundaries of both form and message, expanding the

artistic and civic dimensions of photography.

Moreover, ICP is a

renowned center for photographic education, offering MFA programs and public

courses that train photographers not just as image-makers but as cultural

agents. Its recently opened campus in Manhattan’s Lower East Side signals a

renewed vision for photography as a platform of communication in the digital

era.

For Seoul, the goal

should not be to imitate this model, but to evolve its own institutional

framework—a distinctly Korean ICP, grounded in the region’s realities,

challenges, and creative visions.

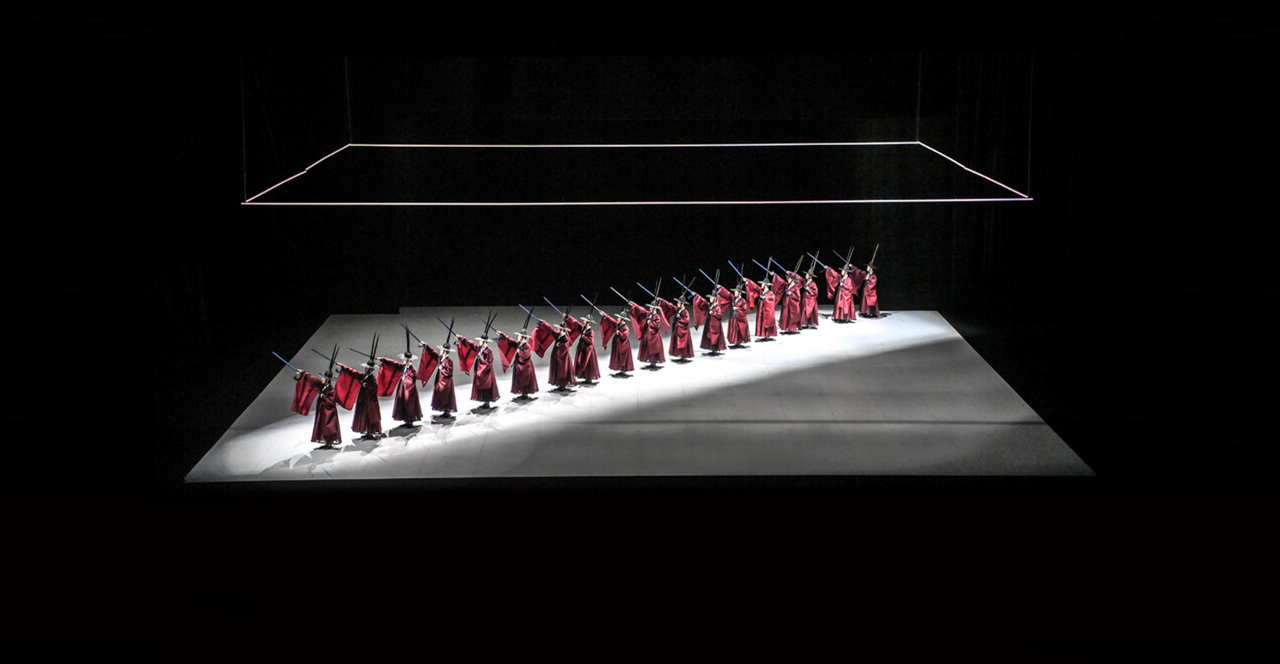

A

Space Is Not Enough

The Seoul Museum of

Photography spans 1,800 square meters and includes exhibition halls,

educational studios, a photo library, darkroom, and a photobook café. It is

designed as a comprehensive structure encompassing the full cycle of production,

exhibition, preservation, and dissemination of photography.

Jointly designed by

Austrian architect Mladen Jadric and Korean firm 1990 Architects,

the building reflects the pixel structure of photographic imagery, merging

medium-specific symbolism with architectural functionality—a rare and

meaningful gesture in institutional design.

Yet no institution

functions through architecture alone. For this museum to truly operate as a

public catalyst, several critical elements must accompany its physical space.

ICP Website Screenshot

Above all,

curatorial experimentation and critical inquiry must be central. Rather than

merely displaying trends in domestic photography, the museum should explore the

medium’s evolving aesthetics, technologies, and sociopolitical

implications—thereby situating photography within a broader contemporary

context. A reinvigorated discourse will help construct the intellectual

architecture that supports and expands artistic practice.

In addition, the

museum must lead the establishment of photographic collections and archiving

systems, which will be vital for building a formalized history of Korean

photography. Until now, the trajectories of contemporary Korean photography

have remained largely undocumented, scattered across private archives. Without

collective record-keeping, solidarity and dialogue remain fragile. It is now

the museum’s role to fill that gap.

A view of ‘The Reference’ in Seochon, a space actively engaging with the challenges and practical discourse of contemporary Korean photography / Photo: The Reference

A view of ‘The Reference’ in Seochon, a space actively engaging with the challenges and practical discourse of contemporary Korean photography / Photo: The Reference

Young emerging artists presenting at ‘Open PT’ alongside the panel of judges / Photo courtesy of: Naver Design Press Blog

Spaces such as The

Reference in Seochon, Seoul, have already demonstrated how critical

dialogue and photographic experimentation can be fostered. Now, institutional

support must be extended to artists on the ground. Educational programs should

go beyond technical instruction and create meaningful encounters between

photographers and society. Instead of conforming to the art fair-centered

market, the museum should build long-term structures that sustain the growth

and maturity of photographic artists.

Korean

Contemporary Photography: Now It Begins

The opening of the

Seoul Museum of Photography marks a major turning point—and an opportunity—for

Korean photography.

But for this

institution to become a genuine engine of transformation, every aspect of its

administration, policy, programming, and curatorial vision must be committed to

institutionalizing the artistic and social force of photography.

Photography is no

longer a shadow of painting or a mere instrument of journalism. It is a

language that captures the world we inhabit with unmatched immediacy and depth.

It is also a form of record that raises the most urgent and precise questions

of our time.

Contemporary Korean

photographers have already proven their value through fierce dedication and

accomplishment.

What they now need

is not validation, but a robust, public, and institutional structure that

enables their continued work.

We hope the Seoul

Museum of Photography will mark the end of this long wait and serve as the

official declaration of a new era in Korean contemporary photography.

This is not simply

the opening of a museum—it is the beginning of a new chapter in the cultural

and institutional history of Korean photography.