Since the early 2020s, the global

art world has undergone a rapid reconfiguration. At the heart of this

transformation is an unprecedented focus on Black artists. From major museum

exhibitions to art fair demand and collector interest, the entire ecosystem

reflects this shift. Yet this isn't merely a passing trend. Rather, it is the

visible outcome of two converging cultural forces: Postcolonialism and

Political Correctness (PC).

These twin 'PCs' each signify a

structural response—the former critiques the legacies of colonialism, while the

latter attempts to address social inequality through institutional and

linguistic inclusion. The rise of Black artists signals that these forces

are no longer peripheral but are actively shaping artistic discourse and

systems.

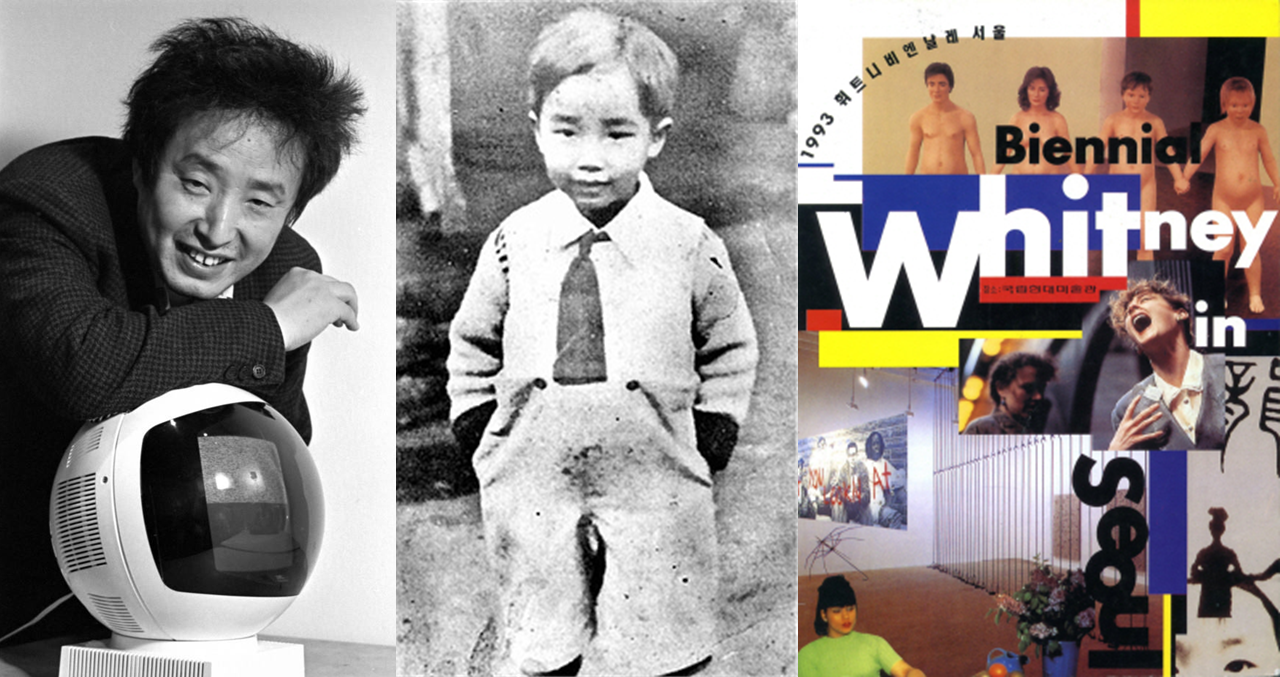

The Shift on the Exhibition Floor

Since 2020, leading art

institutions across the U.S. and Europe have rushed to center Black artists in

major exhibitions. The Whitney Museum in New York, Tate Modern, the New Museum,

SFMOMA, and the Berkeley Art Museum have all featured landmark shows.

These curatorial efforts are not

framed as gestures of diversity alone, but as acts of ethical and

institutional responsibility. Tate, for instance, declared its intent to

"restore perspectives befitting a postcolonial era," and has mounted

group exhibitions focused on artists from the Black diaspora.

Collection policies have shifted

accordingly. Since 2021, Arts Council England has earmarked dedicated budgets

under its Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) guidelines. Major

American museums, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, have

made significant acquisitions of works by Black artists.

The Rise of Artists, The Politics

of Representation

Among the most prominent names in

this wave are Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, Wangechi Mutu, and Mickalene Thomas.

케힌데 와일리(Kehinde Wiley) / Photo by Frank Xavier / ©Out Smart Magazine

Kehinde Wiley upends historical power by

rendering Black male subjects in classical portraiture styles.

에이미 셰랄드(Amy Sherald) / Photo by Tiffany Sage / ©BFA.com

Amy Sherald became internationally recognized for her portrait of former First Lady

Michelle Obama.

왕게치 무투(Wangechi Mutu) / ©Singulart

Wangechi Mutu, originally from Kenya,

dismantles colonial anthropological imagery and reimagines identity through

Afrofuturist aesthetics.

미케일린 토마스(Mickalene Thomas) / Photo by Emil Horowitz / ©Mickalene Thomas

What these artists share is not just identity, but an incisive critique of

historical power. However, the institutional

framing of their work doesn't always foreground this nuance.

Institutional Inclusion or

Ideological Reframing?

DEI (Diversity, Equity,

Inclusion) has become a de facto curatorial protocol. But critiques of this

framework are emerging.

Gavin Jantjes, former Tate

curator and cultural critic, remarked in 《The Times:》

"Many institutions made hurried acquisitions of older Black artists

under the guise of ethical consumption. This isn’t true restitution—it’s more

like a rinse cycle."

Following BLM, many museums

scrambled to acquire works from Black artists active in the 1970s and 80s. Yet

critics argue that such decisions were driven less by aesthetic merit and more

by a desire to symbolically check the box of representation.

From Identity to Token: A

Slippery Slope

This moment of visibility carries

an inherent risk: that under the banner of 'diversity', artists are reduced to

singular emblems.

As Taylor Crumpton wrote in 《Artsy》:

"The tokenization of Black artists flattens their aesthetic complexity

and narrative interiority. They now exist solely as the 'representative Black

artist.'"

(Tokenization refers to the

institutional practice of elevating a minority figure to appear inclusive,

while reducing them to a signifier of identity. Their complexity is sacrificed

for symbolic utility.)

We are thus witnessing a dual

impulse in today’s art world: the restoration of identity and its simultaneous

commodification.

Postcolonial Aesthetics Absorbed

and Depoliticized

Even artists known for deeply

political postcolonial work—such as Yinka Shonibare and Donald Locke—now risk

becoming institutionalized as safe symbols.

In 《New Left Review》, critic Niru Ratnam describes Chris Ofili:

"Ofili didn’t just depict hybridity; he revealed its political tensions

through irony. Institutions stripped that irony and absorbed him as a face of

surface-level PC."

The moment a postcolonial

aesthetic is absorbed institutionally, it runs the risk of being

depoliticized.

What Exactly Are We Restoring?

The current movement can be read

as either institutional progress or performative repetition. The deeper

question is whether it truly restores the subjectivity of the artist.

Identity-based curation is vital,

but when it overrides formal experimentation, personal narrative, and aesthetic

strategy, real diversity becomes hollow.

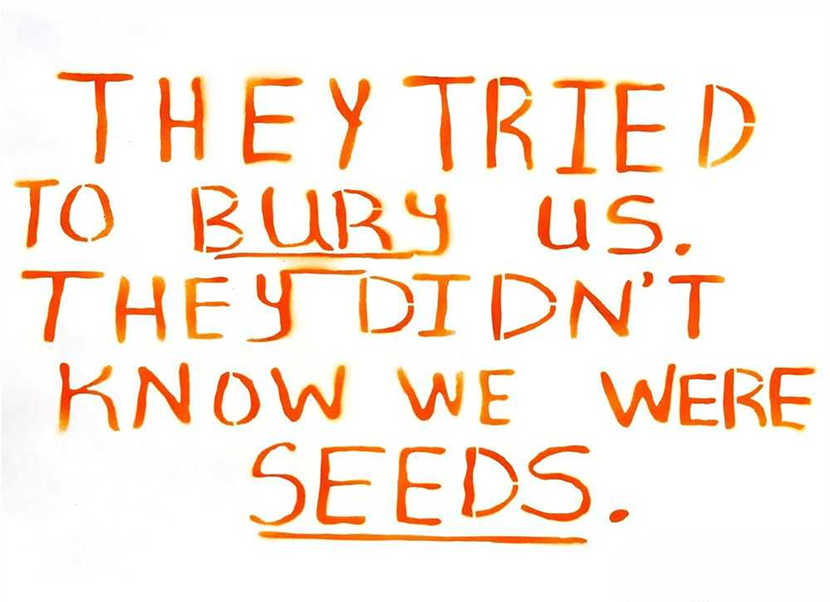

The rise of Black artists is a

positive development, but if their practices are domesticated by a politically

coded distribution system, we may be witnessing a new kind of colonization.

Two PCs, One Trend—And a Mirror

for Korea

The ascent of Black artists today

is not simply about expanding representation. It is proof that the two PC

discourses—postcolonial critique and political correctness—are actively

reshaping art institutions and markets. This is not just about inclusion; it's

about the ideological frameworks that govern inclusion itself.

What "Substance" Is

Korean Contemporary Art Chasing?

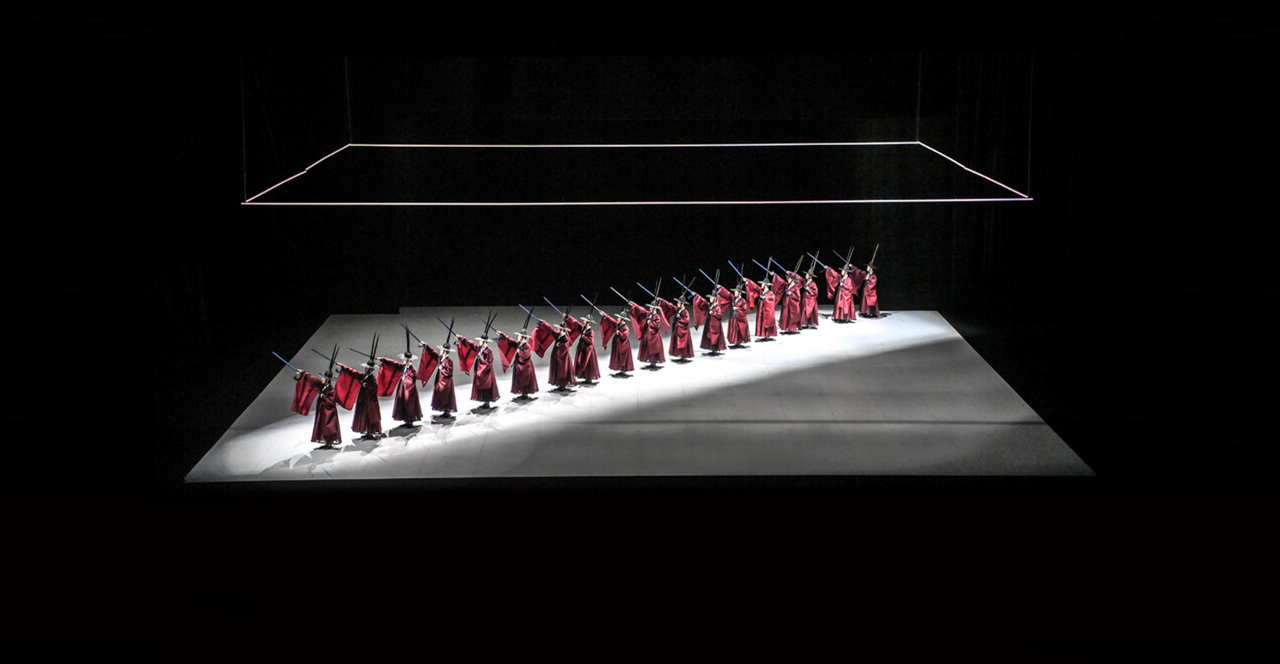

The global rise of

"K-Art" is no longer just about sending Korean artists abroad. It now

poses a deeper question: how does Korean art respond to the moral order

structured by Western cultural hegemony, which has defined the terms of both

PCs?

For decades, Korea has promoted

its national identity through state-led exhibitions. Yet that identity has

often been sanitized—politically neutral, aesthetically safe—produced for

consumption by the Global North.

Korean art must now move beyond

this. It must escape the symbolic choreography demanded by the U.S. and

Europe—nations that designed the languages of diversity and the politics of

correct representation.

The goal is not more invitations

or strategic positioning. It is to build the conditions where individual

artists can confront, negotiate, and resist the world on their own terms.

We now stand before a question we

can no longer evade:

Will Korean contemporary art continue to replicate a "safe identity"

for global consumption, or will it evolve into a subject capable of dissent,

dialogue, and originality?

This is no longer about global strategy. It is a universal question—one

that demands we move beyond the frameworks defined by the West.

References

- - Taylor Crumpton, “Black

Artists, Gallerists, and the Myth of Inclusion,” 《Artsy》, 2020

- Gavin Jantjes, interview with 《The Times》, 2023

- Niru Ratnam, “Chris Ofili and the Limits of Hybridity,” 《New Left Review》, 2005

- "Postcolonial Art," TheArtStory.org

- "Postcolonialism and Art," Tate.org.uk