K-Culture: A Global Phenomenon Still

Expanding

K-Culture continues to expand across

the globe. At〈Music Bank in

Lisbon〉, held in Portugal, artists such as IVE,

Taemin, and RIIZE performed before a crowd of 20,000.

It was not a one-time event but part

of a broader system of performance production and fan-based engagement

operating within the European market.

〈Music Bank in Lisbon〉 / Photo: KBS2

〈Music Bank in Lisbon〉 / Photo: KBS2

Girl group LE SSERAFIM performing on 〈America’s Got Talent〉/ Photo: YouTube capture

Meanwhile, the girl group LE

SSERAFIM became the first K-pop girl group to perform on〈America’s Got Talent〉, presenting an English-language

version of their hit song.

Their appearance on a major U.S.

television network marked more than a milestone—it demonstrated that Korean

popular culture is no longer an imported novelty but an active participant

shaping the global media ecosystem.

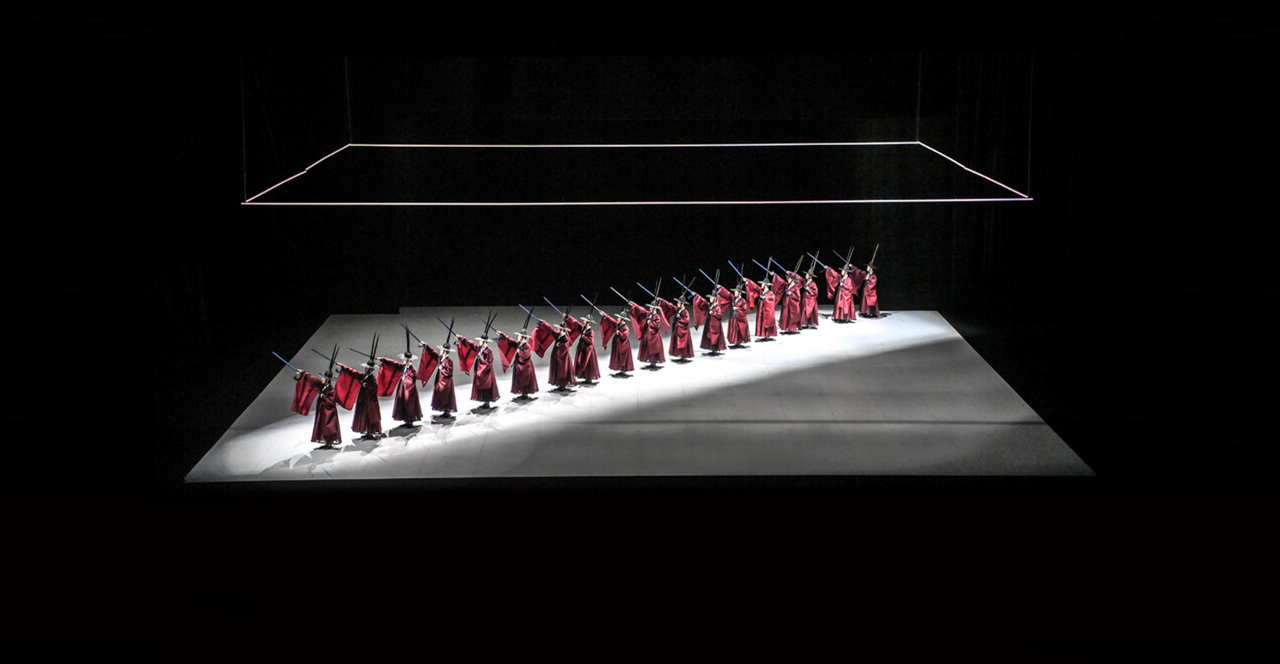

K-POP Demon Hunters: A New Structure for the Korean Wave

Released on Netflix in 2025,〈K-POP Demon Hunters〉became a global sensation, symbolizing K-Culture’s evolution into a multi-layered

cultural system that transcends genre boundaries.

Blending music, animation, gaming

dynamics, and mythological storytelling, the film topped the North American box

office its opening weekend and introduced a new ‘Streaming-Theater-Music’ integrated

distribution model.

EJAE, Audrey Nuna and Rei Ami from 〈K-POP Demon Hunters: Golden〉 | “The Tonight Show” / Photo: YouTube screen capture

It was the first global case of

integrating K-pop fandom culture, the visual language of animation, and the

world-building of games into a unified IP system. K-Culture has thus evolved beyond the

boundaries of a national brand—into a complex cultural network where

narrative, image, sound, and digital infrastructure converge.

K-Culture’s Success Is Not Only About

Creativity

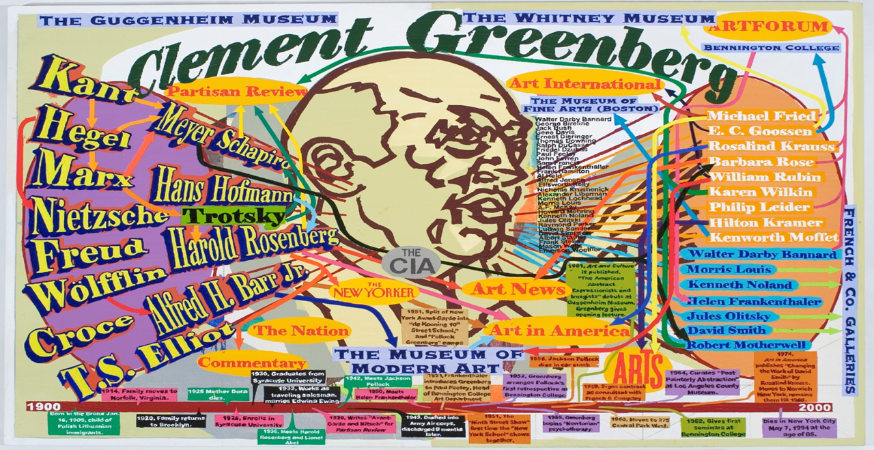

International media and scholars view

K-Culture’s rise as a structural achievement rather

than a mere creative outburst.

France’s ‘Le Monde’ observed

that “In just two generations, Korea has built global influence across music,

film, fashion, and gastronomy—driven by government strategy, private capital,

and export infrastructure.”

Analysts point to four interlocking

forces behind its success: digital platforms, fan-driven ecosystems,

cultural diplomacy, and concentrated private investment—all

enabling creative autonomy within a systemic framework.

In other words, Korea’s global

prominence is not simply a product of “passion,” but of systematic

accumulation and institutional design.

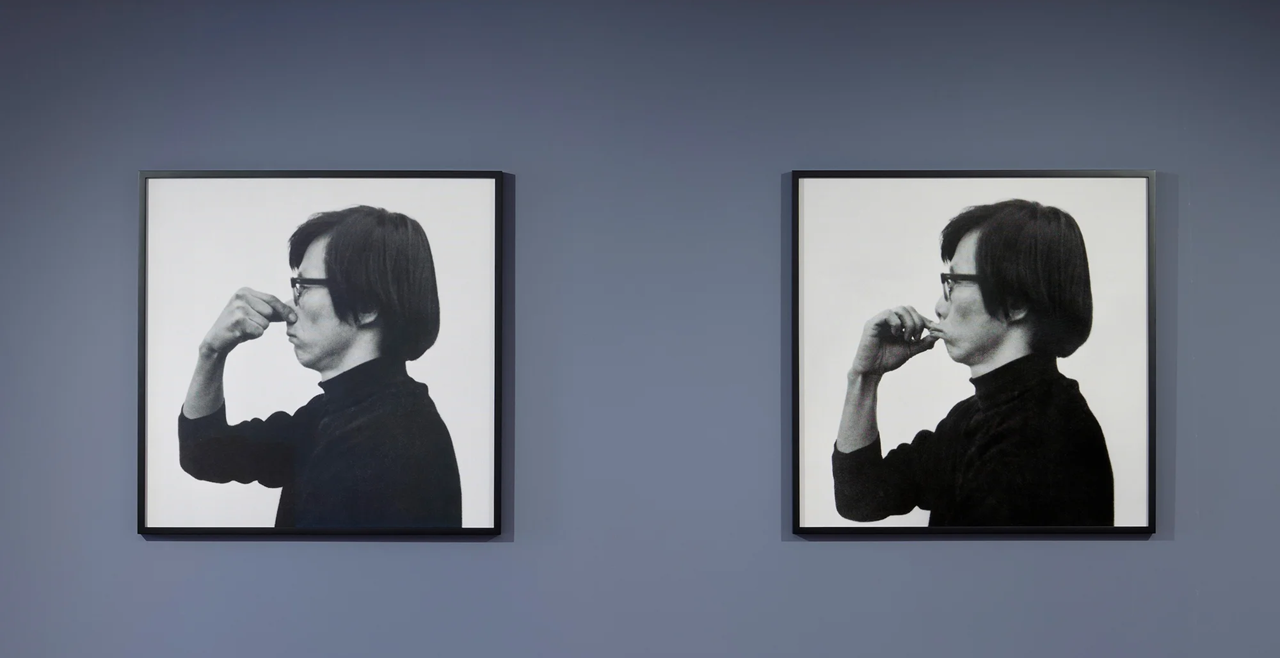

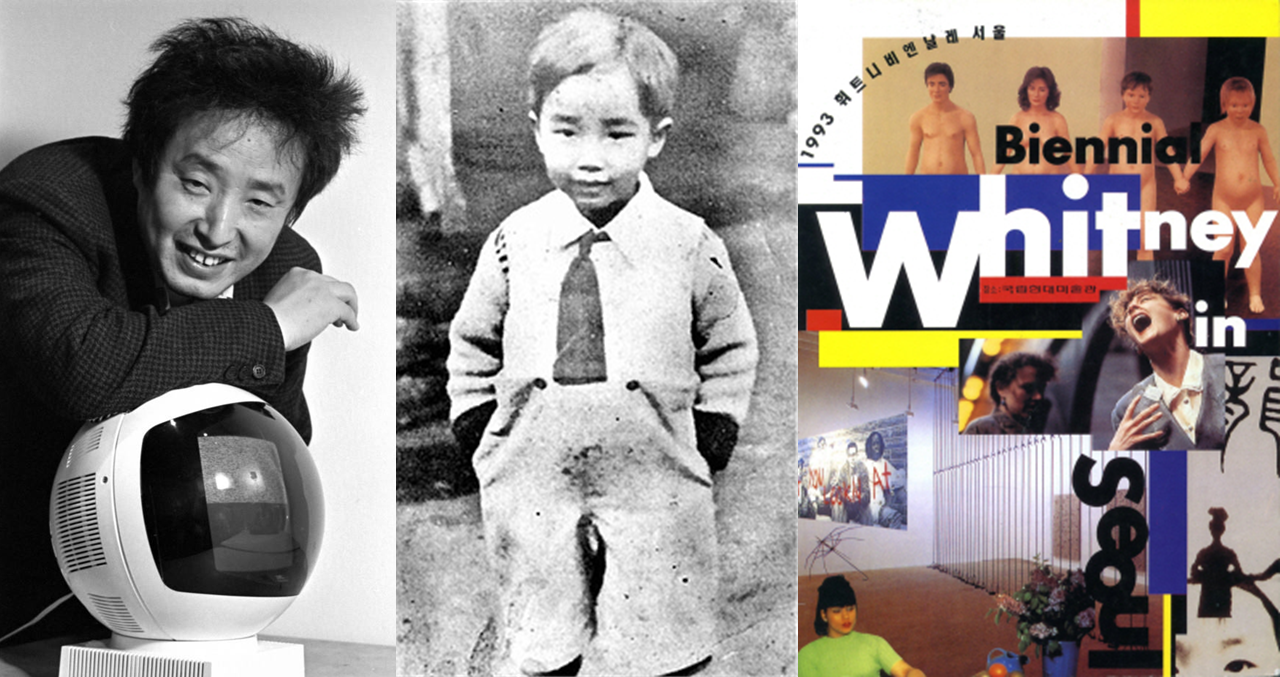

The Current Landscape of Korean

Contemporary Art

Despite economic slowdown, Korean

contemporary art continues to draw international attention. Major museums, biennales, and global

art fairs such as Frieze have increasingly featured Korean artists.

Article on Korean contemporary artists’ overseas expansion / Photo: K-ARTNOW screen capture

However, these achievements rest

largely on individual effort and opportunity, not on

an institutional foundation.

The art world remains bound by an outcome-oriented

administrative framework. Success is still measured by

quantifiable metrics—completed exhibitions, visitor counts, and international

participation—while creative processes, research, and the value of failure

receive little recognition.

What artists truly need is not just

“results,” but time and space to build toward them.

Why Supporting Pure Art Matters

The longevity of culture depends on the

strength of its pure artistic foundation. Popular culture thrives

on the aesthetic depth and reflective imagination nurtured by the fine arts.

When that foundation is weak, culture

becomes a fleeting trend; when it is strong, it renews itself across

generations.

Article on Korean contemporary art professionals’ overseas activities / Photo: K-ARTNOW screen capture

Fine art is not merely one artistic

genre—it is a mirror of how a society thinks, imagines, and defines beauty.

Supporting the arts, therefore, is not

a matter of administrative aid but of expanding a nation’s aesthetic

intelligence and creative capacity. Cultural industries can only

sustain themselves when they continuously generate new forms and languages—and

those always originate from the experimentation and inquiry of pure

art.

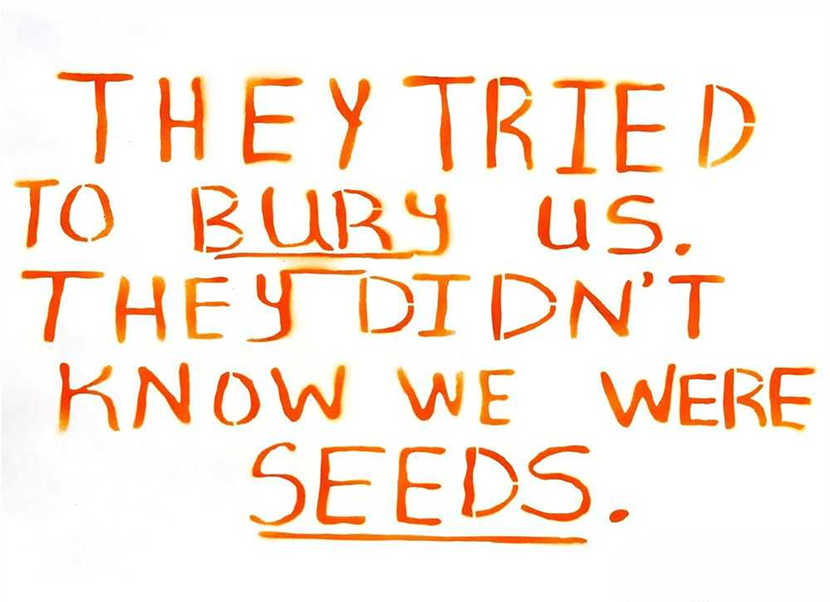

For today’s cultural achievements to

evolve into tomorrow’s industries, Korea must strengthen the production

base of foundational arts. Ultimately, the true measure of a

nation’s cultural level lies in how freely and sustainably its artists can

create.

A country with weak pure arts

may consume culture—but it cannot create it.

Article on Korean contemporary art institutions’ overseas expansion / Photo: K-ARTNOW screen capture

The Structural Problems in Korea’s Art

Policy

Yet current cultural policy gives

insufficient attention to this foundation.

Fine art has been increasingly

marginalized within industrial discourse, and most programs remain focused

on end results—allocating funds to exhibitions, performances, and

distribution stages rather than to research, studio environments, or long-term

production.

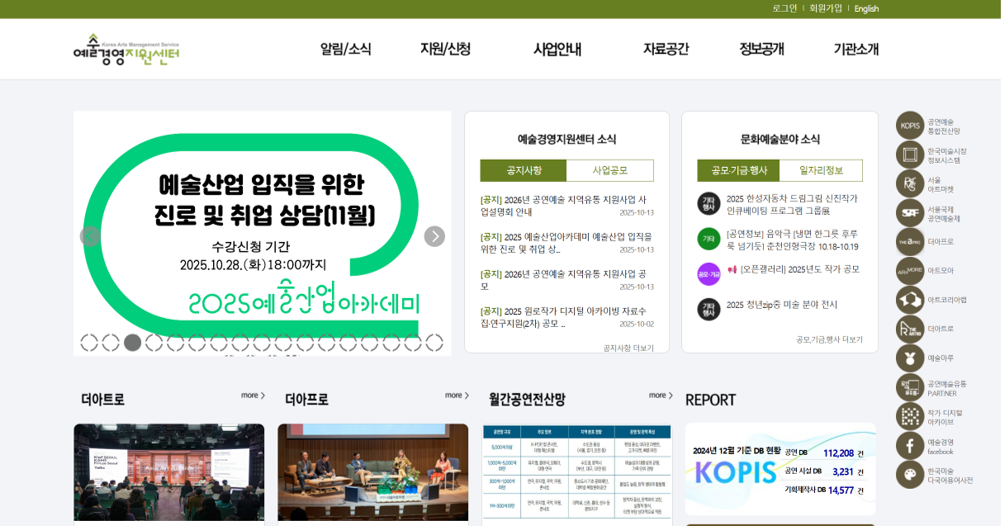

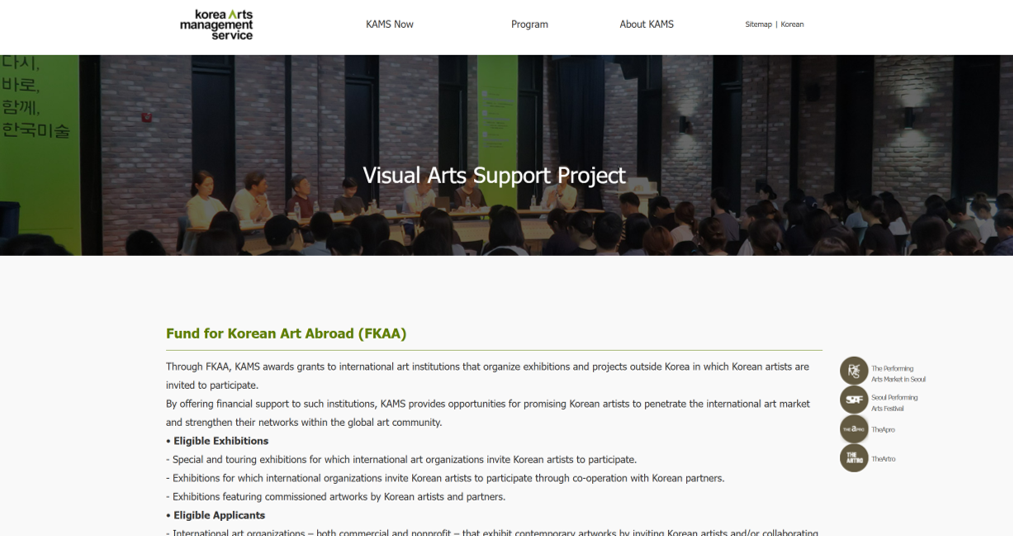

Another serious issue is the lack

of transparency in how grants and budgets are managed. Institutions such as the “Arts

Council Korea” and the “Korea Arts Management Service (KAMS)” rarely

disclose clear data on selection criteria, funding recipients, or the actual

outcomes of their programs.

Without objective evaluation or accountability,

public trust weakens and the gap between artists and administrators widens.

This structure falls far short of

international standards. While leading cultural nations invest in transparent

evaluation and long-term support to foster diversity and experimentation, Korea

remains mired in short-term, opaque, results-based administration.

As a result, the creative soil of fine

art continues to erode—posing a fundamental threat to the sustainability of

Korean culture itself.

This system does not nurture

continuous creation; it instead treats completed works as consumable

products,reinforcing the very commodification it claims to

overcome. Such logic contradicts the government’s stated goal of building a

“cultural ecosystem.” A true ecosystem is one of circulation and

growth, not a collection of short-term outputs.

Particularly in the visual arts,

support for studios, research, archives, and long-term projects remains

minimal, leaving individual artists to struggle with unstable livelihoods and

limited institutional backing.

Consequently, many young artists

succeed abroad yet remain precarious at home—trapped between commercial

dependency and systemic neglect. This is not merely an individual

challenge but a structural failure of national cultural policy.

How Cultural Powerhouses Sustain Their

Systems — Institutionalizing the Arts

Germany, France, and the United

Kingdom have long recognized foundational artas a

pillar of national competitiveness.

In Germany, the federal and

state governments jointly support artist studios and “Kunsthalle

institutions”, providing space and funding for experimental and long-term

projects.

In France, the “Centre

National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP)” offers grants and production funding

to artists, while public residencies in cities like Paris and Marseille treat

artists not merely as producers but as researchers contributing to

collective knowledge.

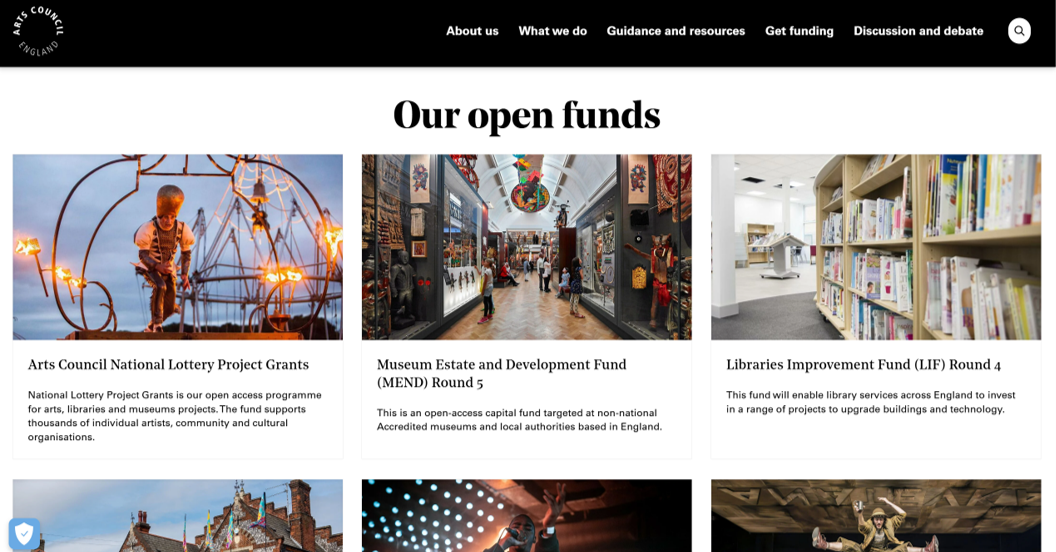

In the United Kingdom, “Arts

Council England” prioritizes artistic value over predictable outcomes, funding

projects even when results are uncertain—some operating on three-year

or longer terms.

These nations view art not as an

accessory to the economy, but as a means through which society

imagines its future.

Screenshot of the Arts Council England website

Screenshot of the Arts Council England website

Screenshot of the Korea Arts Management Service website

Structural Issues in Korea’s Fine Art

Policy

Korea’s fine art policy remains bound

to a performance-driven administrative model.

Government agencies allocate budgets

based on measurable results—exhibitions completed, international showcases

held—while the essential creative process of research, experimentation, and

accumulation receives little institutional support.

Most funding programs lack global

standards, clear objectives, or long-term vision. Budgets are

typically short-term or one-off, making sustained artistic research nearly

impossible.

Support for basic content production

systems—studios, materials, research—is persistently neglected, trapping

artists in a cycle of dependency on short-term outcomes and commercial returns.

Screenshot of the Korea Arts Management Service website

Realistic Strategies for the

Globalization of Korean Art

For Korean contemporary art to

establish itself as a core site of global art production, a

fully restructured infrastructure tailored to fine art is essential.

Screenshot of the Korea Arts Management Service website

Artists must be granted the institutional

time and flexibility to research and even fail.

A multi-year creation grant

system—spanning three to five years—should redefine artistic work as a process

of knowledge production, not merely a deliverable.

Equally urgent is the establishment of a national

digital archive system that integrates records of artists,

exhibitions, and critical writing, while making them accessible

internationally. Such archives form the foundation of credibility and serve as

a cultural legacy of the nation. Without this infrastructure, true global

outreach will remain impossible—a reality still widely overlooked in Korea’s

art ecosystem.

The Korean art world must now take

inspiration from the success of K-Culture and pursue structural

reform for sustainability.

This means dismantling outdated

frameworks and building an infrastructure aligned with global standards.

Only through such transformation can the

vibrant wave of K-Culture evolve into the era of K-Art. Then,

and only then, will Korean art stand as both a producer and a

birthplace of pure artistic creation on the world stage.