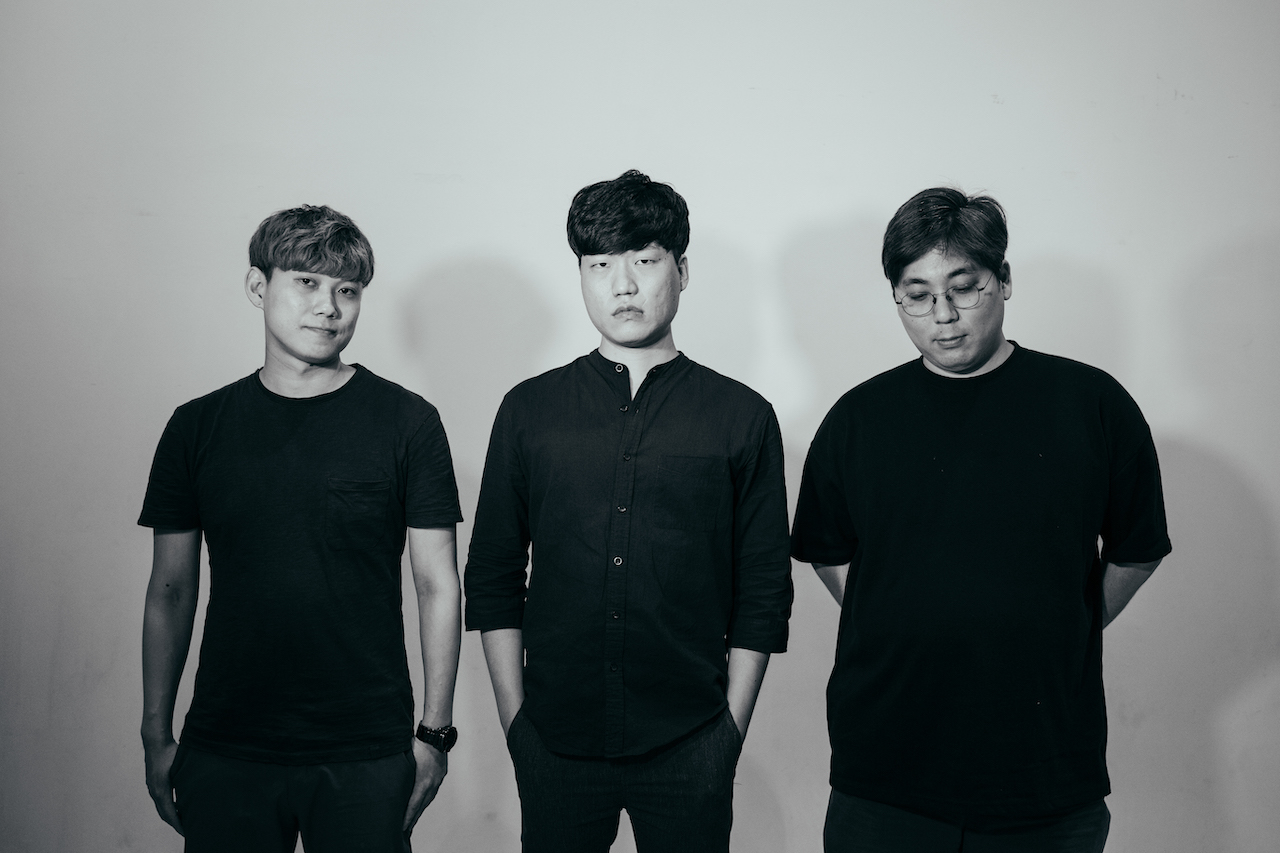

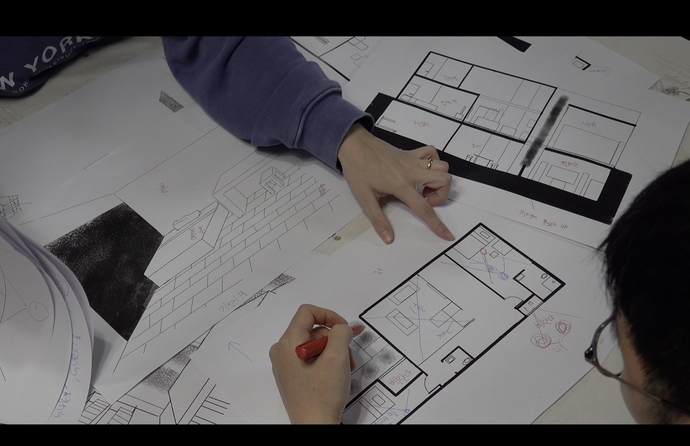

Hilma af Klint’s ‘The Ten Largest’ installed in the highlight space. /Busan Museum of Contemporary Art

In 1907, a woman painted large

circles and spirals on canvas—forms that would now be recognized as abstract

art. Yet, her name remained absent from the 20th-century art historical canon

for decades. Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), the Swedish artist whose work long

awaited a “timely summoning,” has finally come into full view through her first

large-scale touring exhibition in Asia.

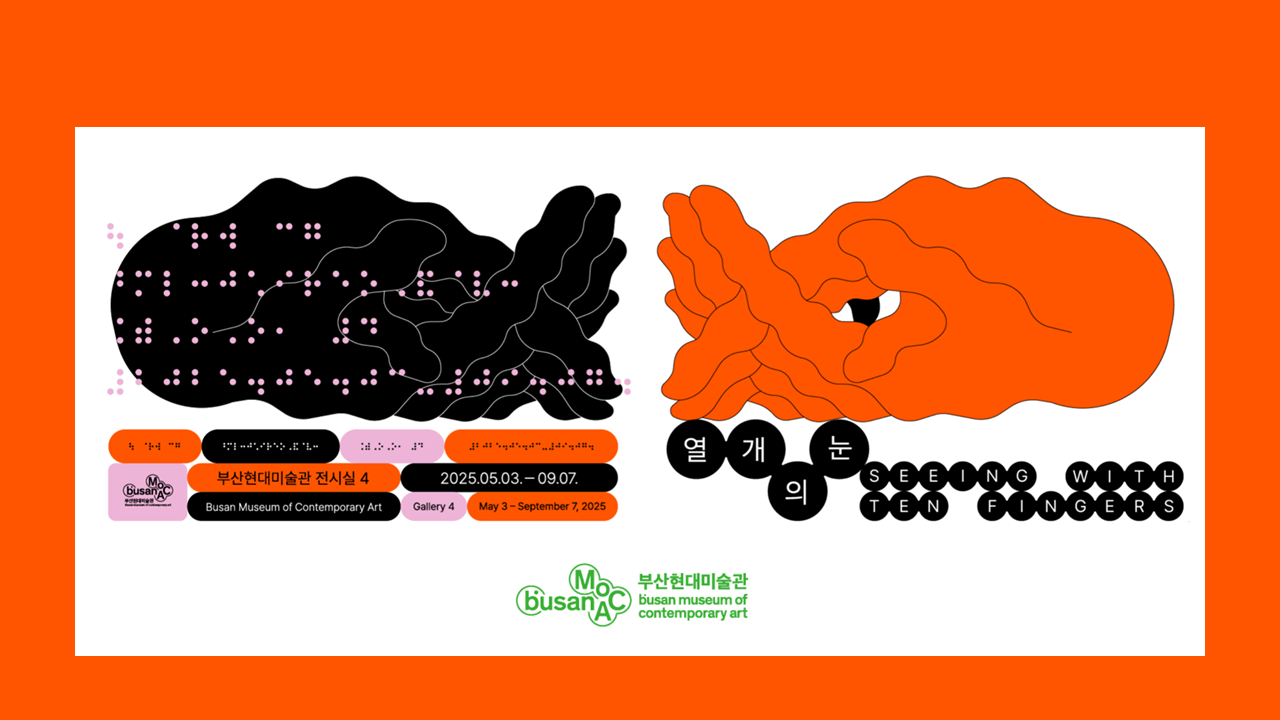

The Busan Museum of Contemporary

Art, in collaboration with the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, opened the

exhibition 《Hilma af Klint: A Timely Summoning》 on

July 19. Devoted to depicting the “invisible world,” af Klint’s works are

presented here through 139 pieces, including major series, drawings, notebooks,

and archival materials that trace the arc of her life and thought. The

exhibition runs until October 26.

Hidden Time, Sealed Paintings

By the mid-1910s, af Klint had

already produced hundreds of non-figurative works. Yet, convinced that her

contemporaries would not understand them, she left behind explicit

instructions: “Do not show my paintings for 20 years after my death.” Over

1,300 works and 26,000 pages of notes were locked away in her nephew’s attic,

unseen until a 1986 group show in Los Angeles. Even then, she received little

attention. It wasn’t until the 21st century that her work began to receive the

recognition it deserved. Major retrospectives at the Moderna Museet in

Stockholm (2013) and the Guggenheim Museum in New York (2018) drew hundreds of

thousands of visitors and forced a rewriting of modern art history.

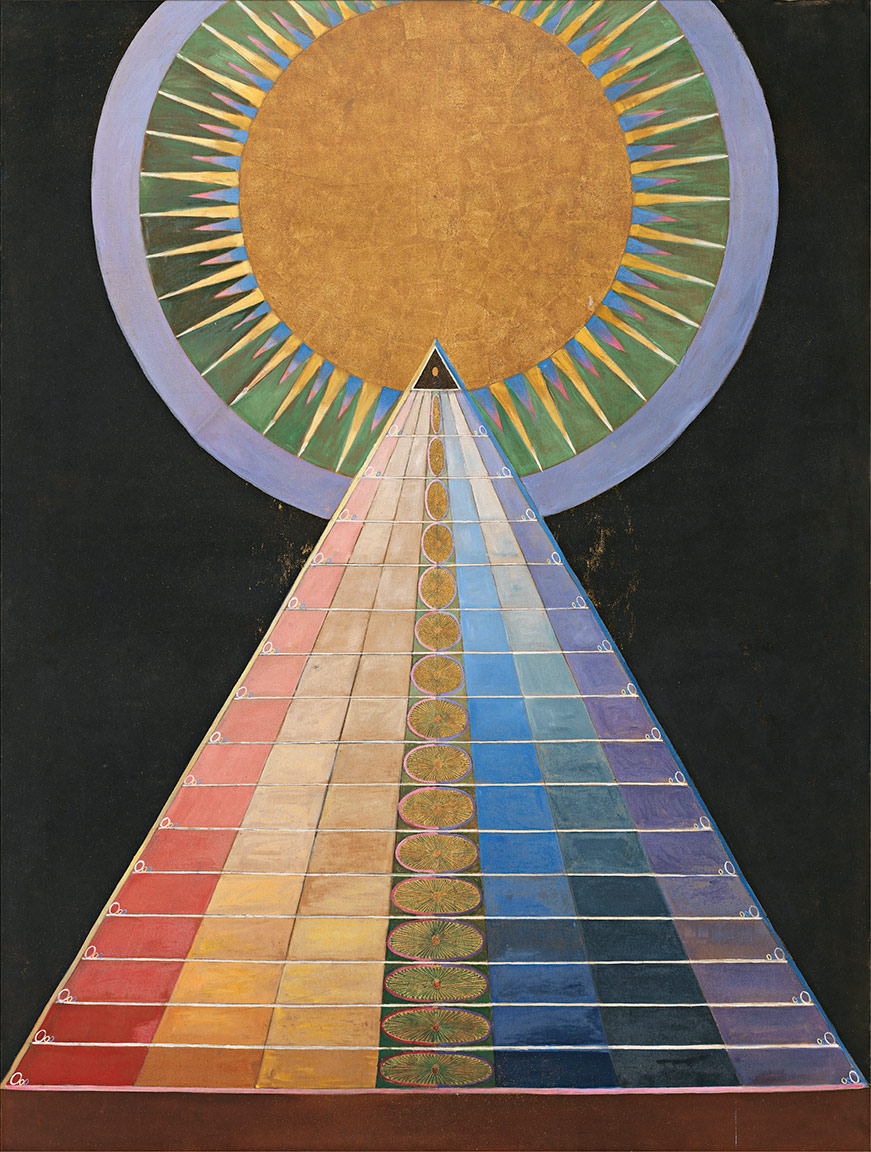

〈No. 7,

Adulthood, Group IV〉, 1907, from ‘The Ten Largest’. tempera

on paper mounted on canvas, 315×235 cm. /Busan Museum of Contemporary Art

〈No. 7,

Adulthood, Group IV〉, 1907, from ‘The Ten Largest’. tempera

on paper mounted on canvas, 315×235 cm. /Busan Museum of Contemporary Art

The First to Paint the Invisible?

Five years before Kandinsky’s

famed 1911 abstract work, af Klint had already created large-scale compositions

devoid of traditional form—yet filled with symbols, symmetry, and hidden order.

She didn’t see them as mere artworks, but as transcriptions of messages

received from a higher realm.

Living at the intersection of

mysticism and rationality in early 20th-century Europe, she immersed herself in

Theosophy—a spiritual movement that sought to uncover the unseen dimensions of

reality. Her art became a visual language through which she explored profound

existential questions.

〈No. 1, Group X, Altarpiece〉, 1915,

237.5×179.5 cm. /Busan Museum of Contemporary Art

〈No. 1, Group X, Altarpiece〉, 1915,

237.5×179.5 cm. /Busan Museum of Contemporary ArtHer process was not simply an

aesthetic pursuit. “I was instructed by a higher order,” she once wrote. Her

paintings were not images, but revelations. Ironically, Rudolf Steiner—the very

Theosophist she admired—dismissed her methods as inappropriate and out of step

with her era. The world, it seemed, was not ready.

Monumental Scale, Meticulous

Order

The highlight of the exhibition

is ‘The Ten Largest’—a series of ten massive tempera paintings, each

over 3 meters high, which symbolize the four stages of human life: childhood,

youth, adulthood, and old age. Swirling forms, vibrant color fields,

symmetrical structures, and recurring symbols coalesce into a cohesive visual

symphony. Af Klint completed the entire series in just two months. Far from a

formal experiment, these paintings form a spiritual narrative—a cosmology

rendered through form.

How Should We Speak of Hilma?

This exhibition refuses to reduce

af Klint to the title of “the first abstract artist.” Instead, it follows the

spiritual and philosophical structures that underlie her work—whether in ‘Paintings

for the Temple’, ‘The Atom’, or her many ‘Untitled’ drawings. Her

work embodies not only a metaphysical vision but also a feminist gesture: the

creation of a symbolic, collaborative space, as seen in her spiritual group

“The Five.”

In her final years, af Klint

returned to botanical studies. But this was not a retreat into the past; it

served to complete the trajectory of a life-long inquiry—a circular return that

closed her artistic arc.

힐마 아프 클린트(Hilma af Klint, 1862~1944)

Hilma af Klint was among the rare

women of her time to receive formal training at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts

in Stockholm. She began her career painting natural subjects—plants, animals,

portraits, and landscapes—but gradually shifted her focus toward the invisible.

Deeply engaged with Theosophy, she believed her art to be a conduit for

spiritual messages and cosmic order.

Convinced that her time was not ready for

such visions, she instructed that her work remain unseen for two decades after

her death. It was not until the 21st century that af Klint was finally

recognized as a pioneering figure—reshaping our understanding of the origins of

abstract art.