Kim Jipyeong (b. 1976) has presented works

that explore contemporary themes through the techniques and styles of Oriental

painting, or Korean traditional painting. Rather than viewing the past and

present as opposing forces or focusing on modernizing tradition, the artist

aims to discover the contemporary within tradition by considering what has been

omitted from both realms.

Kim Jipyeong,

Still Life-Scape, 2007 ©Kim Jipyeong

Kim Jipyeong,

Still Life-Scape, 2007 ©Kim JipyeongFrom 2001 to 2012, she primarily presented paintings that reinterpreted traditional Korean folk art styles, such as Chaekgeori (still-life paintings of books and stationery), Munjado (paintings of Chinese characters), and Hwajodo (paintings of flowers and birds), as well as the decorative elements of Dancheong (traditional Korean decorative coloring on wooden buildings). Using acrylic paint, she modernized these styles to suit the times, gaining early recognition for her vibrant ‘Chaekgeori’ series.

Kim Jipyeong,

Michaesansu (迷彩山水圖) - Mushroom Mountain, 2008 ©MMCA

Art Bank

Kim Jipyeong,

Michaesansu (迷彩山水圖) - Mushroom Mountain, 2008 ©MMCA

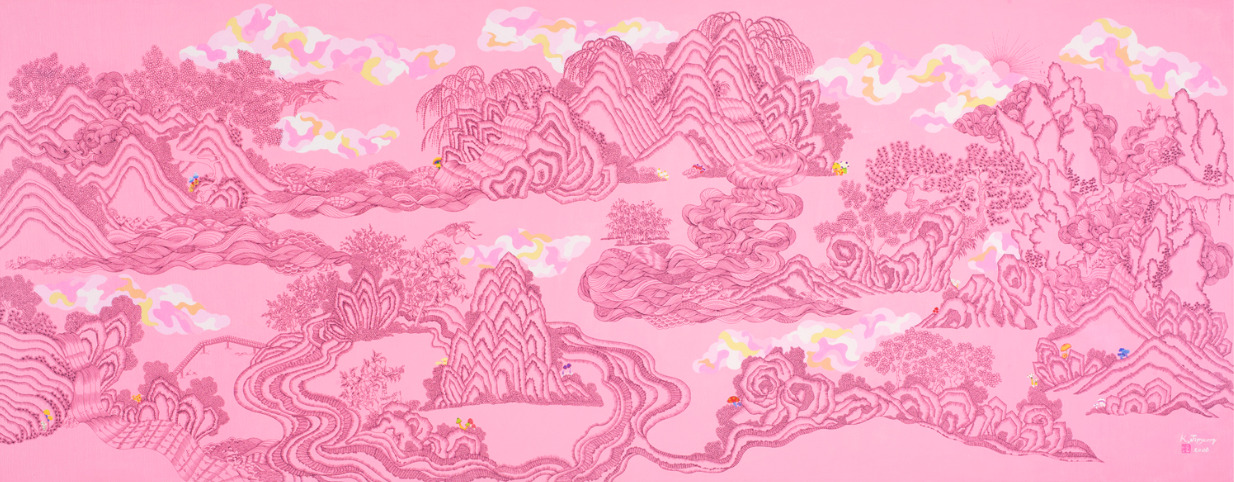

Art BankKim Jipyeong's early works reflect her

exploration of the interaction between tradition and contemporaneity, as well

as between folk elements and modern art. For instance, her 2008 work

Michaesansu (迷彩山水圖) - Mushroom

Mountain incorporates a distinctly contemporary Korean landscape into

the traditional formats of Sansuhwa (Korean landscape painting) and folk

art.

The word “Michae” (迷彩) in the title translates to “camouflage,” a term commonly

associated with military concealment or deception. From a distance, the

painting appears to be a beautiful traditional landscape, but upon closer

inspection, military markers hidden within the mountains emerge, prompting

reflections on the meanings concealed within familiar sceneries.

By embedding camouflage patterns, symbolic

of military deception, into the traditional landscape format, Kim not only

evokes another layer of concealment and illusion but also mirrors the realities

of the “here-and-now” while simultaneously creating a sense of fantasy.

Kim Jipyeong, Pyeongan-Do, 2014 ©Kim Jipyeong

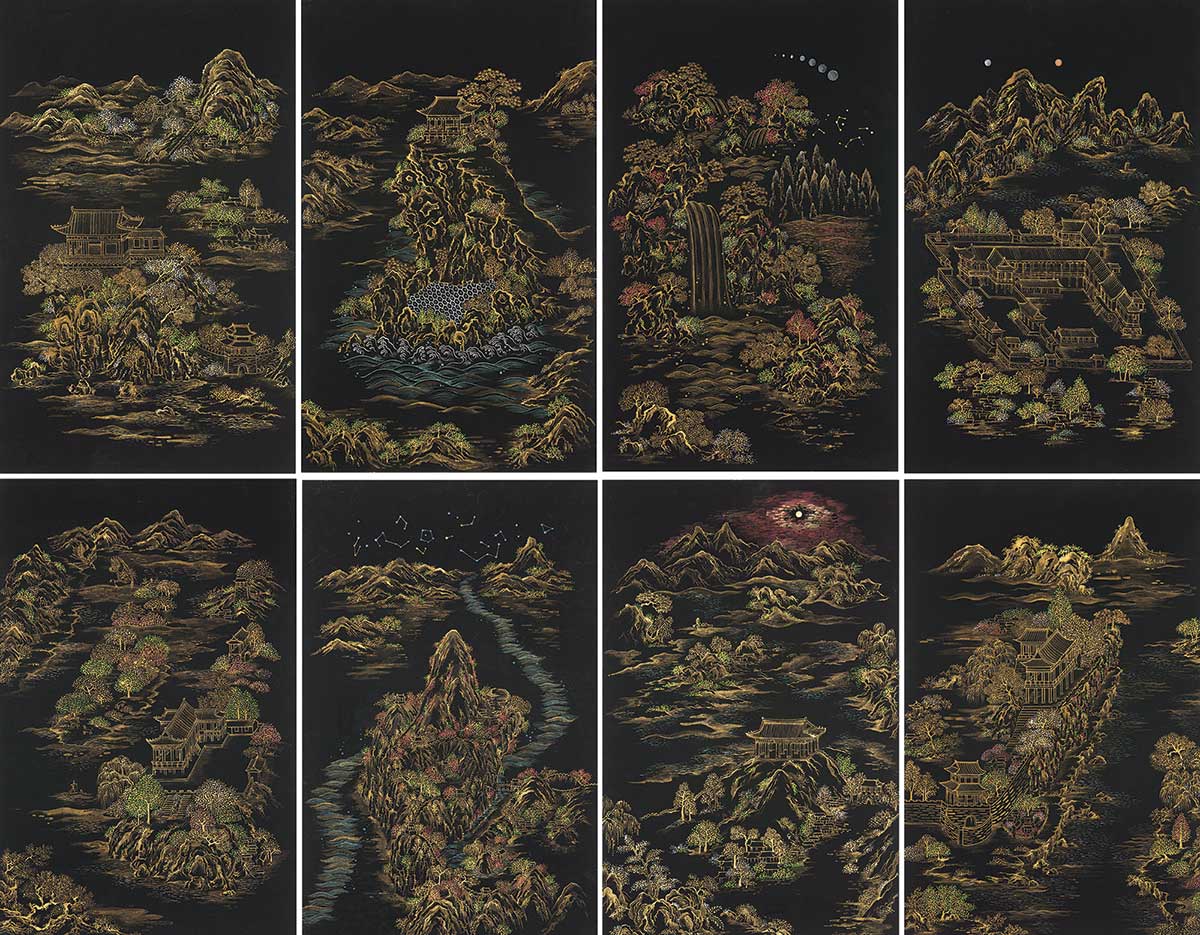

Since 2013, the artist delving into the

materials, theories, and philosophical concepts of Oriental painting while

connecting them to the present. For example, in her 2015 solo exhibition 《Pyeongan-Do》 at Art Company GIG, Kim

addressed themes of family history and the division of the Korean Peninsula

through the format of old maps and the Geumnihwa (gold pigment painting)

technique.

In this exhibition, Kim presented works

centered on Pyeongan Province, her mother’s hometown. Due to the division of

Korea, she was unable to witness Pyeongan Province directly, so she traveled

and imagined its landscapes through various resources, including literature,

paintings, and maps. For instance, she studied the topography by comparing

historical maps she had collected with Google Earth and indirectly experienced

the sentiments of Pyeongan Province through its written descriptions and

anecdotes, reconstructing its essence from the past.

Kim Jipyeong,

Kwanseopalgyeong (關西八景), 2014 ©Kim Jipyeong

Kim Jipyeong,

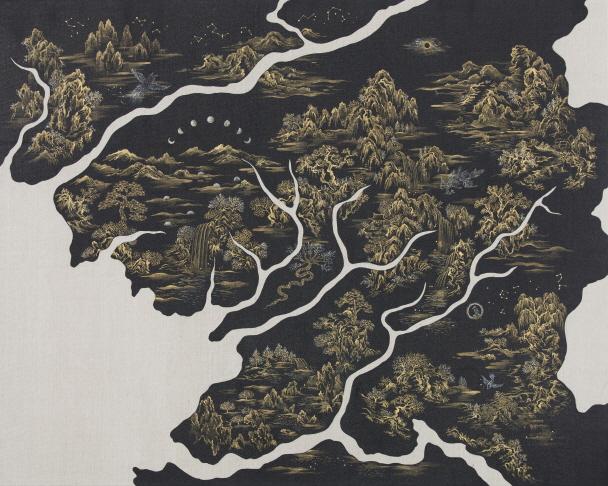

Kwanseopalgyeong (關西八景), 2014 ©Kim JipyeongUsing

her collected materials and imagination, Kim Jipyeong reinterpreted Pyeongan

Province—a place she could neither visit nor experience firsthand—through the

techniques of Oriental painting. In Kwanseopalgyeong (關西八景)

(2014), which beautifully depicts eight scenic spots of Pyeongan Province, Kim

employed the Geumnihwa technique, a method that first emerged during the

mid-Joseon period.

Geumnihwa

involves painting landscapes with gold pigment on black silk or paper,

traditionally used for royal court decorations or paintings reserved

exclusively for the king, symbolizing authority and grandeur. By applying this

technique, Kim transformed Pyeongan Province into a splendid and fantastical

landscape. Through this process, she reframed the region not solely as a site

of tragic history and conflict but as a mysterious and beautiful space.

Installation view

of 《Jaenyeodeokgo (才女德高)》 (Hapjungjigu, 2017) ©Hapjungjigu

Installation view

of 《Jaenyeodeokgo (才女德高)》 (Hapjungjigu, 2017) ©HapjungjiguKim Jipyeong extensively researches

folktales, myths, travelogues, and historical texts, focusing on marginalized

narratives and excluded traditions hidden within them. Paintings from the

Joseon dynasty, dominated by a Confucian worldview, were often created based on

male-centered culture. Kim highlights the elements omitted or deemed taboo

during that period—such as women, sexual desire, shamanic paintings, Buddhist

art, and underground narratives—and incorporates these as key themes in her

work.

In her 2017 solo exhibition 《Jaenyeodeokgo (才女德高)》 at Hapjungjigu, Kim emphasized the language of femininity that had

been taboo in traditional paintings, presenting works that liberate this

forbidden language. The exhibition title, “Jaenyeodeokgo,” translates to “A

talented woman possesses great virtue.” It is both a challenge to the Confucian

value system that suggested women should lack talent to be virtuous and a

provocative question about the nature of “feminine talent.”

Kim Jipyeong,

blood and wine, 2017 ©Kim Jipyeong

Kim Jipyeong,

blood and wine, 2017 ©Kim JipyeongThe works showcased in the exhibition

commonly featured symbols associated with femininity, such as yeonjigonji

(traditional Korean red dots applied on the cheeks and forehead of women),

leopard patterns used in wedding ceremonies as protective charms, jokduri (a

traditional Korean bridal headpiece), as well as motifs from traditional

iconography, including minhwa (folk paintings), portraits of beautiful women

(miindo), and realistic landscape paintings (silgyeongsansu). Additionally, the

pieces incorporated flowing liquids reminiscent of bodily substances like blood

and tears, evoking a visceral sense of femininity.

Among the works, the landscape painting

blood and wine (2017), inspired by Eastern and Western

folktales and myths about menstruation, metaphorically addressed traditional

taboos surrounding women. To achieve this, Kim used cinnabar—a vivid red

pigment traditionally used in amulets in Korea—to "profane" the

depiction of women and landscapes. By doing so, the artist confronted and

challenged the taboos embedded in tradition.

Kim Jipyeong,

Neungpamibo (凌波微步), 2019 ©Kim Jipyeong

Kim Jipyeong,

Neungpamibo (凌波微步), 2019 ©Kim JipyeongKim Jipyeong’s spirit of challenge

continued in her 2020 exhibition 《Friends from Afar》 at Boan1942. In this exhibition, she presented works that utilized

janghwang (the decorative mounting used for scrolls or folding screens). The

artist was particularly drawn to the fact that the names of various parts of

the janghwang—such as chima (skirt), jeogori (jacket), and somae (sleeve)—are

metaphorically associated with women’s clothing.

Focusing on the corporeality embedded in

janghwang, Kim removed the traditional paintings usually placed within folding

screens or scrolls and filled the space with the janghwang itself, transforming

each screen into a representation of diverse individuals. For instance, in her

ten-panel folding screen work Neungpamibo (凌波微步) (2019), she depicted the writings of ten female literati

from the Joseon dynasty.

These women writers, despite their literary

talents, were largely unrecognized and have been remembered only through

written records. Kim gave these forgotten figures a new sense of “embodiment”

by symbolizing them through various pieces of silk that she matched to the

characteristics of each writer. In doing so, she brought physicality and

presence to lives that had previously existed only as text.

Kim Jipyeong, Diva-Shamans, 2023 ©Kim Jipyeong

In her 2023 solo exhibition 《Painting Lost》 at INDIPRESS, Kim presented

another series of scroll works titled ‘Diva’ (2023), which symbolize

individuals erased or marginalized in history. The “divas” Kim focused on

include European gothic female vocalists who challenged the male-dominated

conventions of rock music, Korean shaman women who have been dismissed as

“vulgar,” and grandmothers in Korea who endured sacrifices within the

constraints of a patriarchal society.

Kim Jipyeong,

Painting Lost, 2021 ©Kim Jipyeong

Kim Jipyeong,

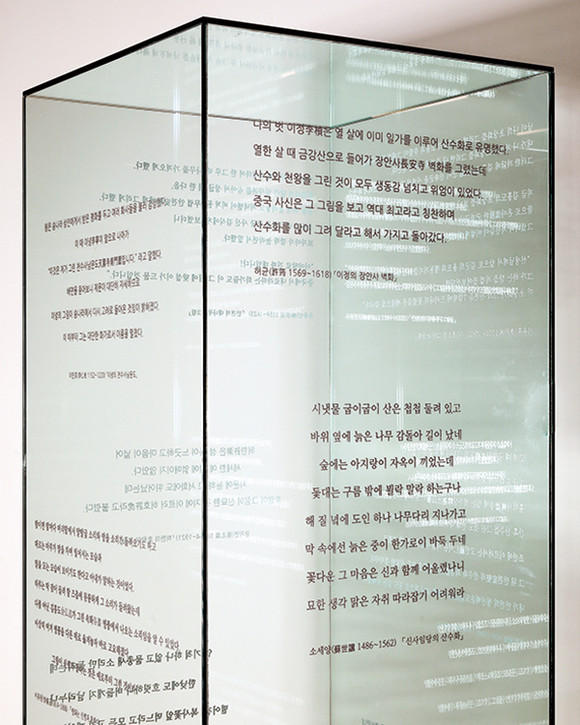

Painting Lost, 2021 ©Kim JipyeongIn the same exhibition, Painting

Lost (2021) was another significant piece that focused on the theme

of absence. This work revolved around the landscape paintings of Shin Saimdang,

which, while documented in historical texts and records, no longer exist today.

The work literally embodies the concept of a “lost painting.” It features a

glass display case, resembling those found in museums, with silkscreened text

on the exterior describing the missing artwork.

Kim Jipyeong, Painting Lost (detail), 2021 ©Kim Jipyeong

The empty case and the text praising the

lost landscape painting symbolize the fragile existence of Shin Saimdang’s

work, now preserved only in written form. Next to it, Kim placed a colorful,

but folded folding screen that could not be seen.

Art critic Moonjung Lee commented on the

piece, noting, “The empty glass box, the text about the painting, and the

folded, unseen screen reflect the artist’s ongoing engagement with themes such

as the fragmentation and loss of tradition, the politics of viewing, museum

practices of exhibition and preservation, and the history of East Asian art.”

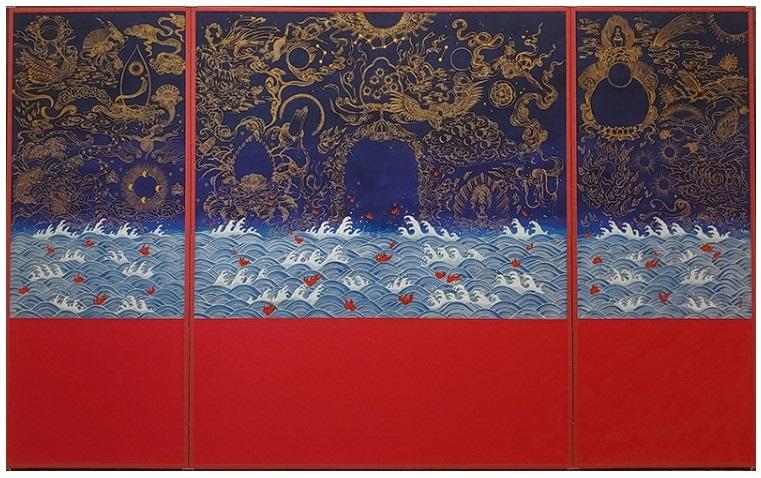

Kim Jipyeong, Gwangbae (光背), 2020 ©Kim Jipyeong

Along with this, Kim Jipyeong also focused

on Buddhist paintings and military portraits, which have often been regarded as

peripheral and neglected in traditional culture. She took note of the fact that

religious paintings always include elaborate decorations surrounding the divine

figures. Drawing from this observation, she removed the divine figures from her

works and left only the decorative elements behind.

The triptych Gwangbae (光背) (2020) features only the traditional decorative icon of

the gwangbae (halo), which is typically drawn around divine beings. A gwangbae

is a symbolic adornment that represents the greatness and transcendence of the

divine. By removing the divine figure and leaving only the gwangbae, Kim

conveys an era in which divinity and sacredness have disappeared.

In her paintings, the absence of the divine

carries neither a negative nor a positive meaning. It suggests that the divine

might have vanished from the scene or could still be waiting to arrive, leaving

an empty space behind.

Kim Jipyeong,

Diva-Grandmothers, 2023, Installation view of 2024 Busan

Biennale (Choryang House, 2024) ©Busan Biennale

Kim Jipyeong,

Diva-Grandmothers, 2023, Installation view of 2024 Busan

Biennale (Choryang House, 2024) ©Busan BiennaleIn this way, Kim Jipyeong does not lean

exclusively toward either simply borrowing traditional symbols or updating the

inherent meanings of tradition in a modern context. She confronts the fixed

concepts and rules embedded in Eastern traditional art, such as traditional

painting, landscape painting, and folk painting, and reinterprets them in an

innovative way. By combining elements that have been excluded from the

histories of art, society, and culture, she generates new meanings.

"I want to break free from the preconception that tradition must be modernized. The goal is not to modernize tradition because it is pre-modern, but to discover the contemporary within tradition." (Kim Jipyeong, Vogue Interview, 2024.02.03)

Artist Kim Jipyeong ©Busan Biennale

Kim Jipyeong graduated from the Department

of Oriental Painting at Ewha Women’s University and received a master’s degree

from the Department of Art Education at its graduate school. Since her first

solo exhibition 《Vivid Drop》 at

Gyeongin Museum of Fine Art in 2001, Kim has held numerous solo exhibitions,

including 《Brilliant Texture》

(Gana Contemporary, Seoul, 2013), 《Pyeongan-Do》 (Art Company GIG, Seoul, 2015), 《Jaenyeodeokgo

(才女德高)》 (Hapjungjigu, Seoul,

2017), 《Kiam Yeoljeon (奇巖列傳)》 (Gallery Meme, Seoul, 2019), and 《Friends

from Afar》 (Boan1942, Seoul, 2020).

Kim also participated in numerous group

exhibitions, including those at the ThisWeekendRoom (Seoul, Korea), Seoul

Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea), Art Space Pool (Seoul, Korea), Fengxian Museum

(Shanghai, China), Lee Ungno Museum (Daejeon, Korea), and INDIPRESS (Seoul,

Korea). Kim was one of the twenty artists selected for the 21st SongEun Art

Award (SongEun Art and Cultural Foundation, Korea) and participated in the 2024

Busan Biennale.

Her work is included in the collections of

the Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea), MMCA ArtBank (Gwacheon, Korea), Gana

Art Gallery (Gwacheon, Korea), Hana Bank (Seoul, Korea), Amorepacific Museum

(Seoul, Korea), and Hankook Chinaware (Chungju, Korea).

References

- 김지평, Kim Jipyeong (Artist Website)

- 보그, 가장 동시대적인 한국화에 대하여

- 국립현대미술관 미술은행, 김지평 - 미채산수도(迷彩山水圖)-Mushroom Mountain (MMCA Art Bank, Kim Jipyeong - Michaesansu (迷彩山水圖) - Mushroom Mountain)

- 아트 컴퍼니 긱, 평안도 (Art Company GIG, Pyeongan-Do)

- 합정지구, 재녀덕고 (Hapjungjigu, Jaenyeodeokgo)

- 유아트스페이스, 김지평 – blood and wine (UARTSPACE, Kim Jipyeong - blood and wine)

- 다아트, [이문정 평론가의 더 갤러리 (106) 김지평 개인전 ‘없는 그림’] ‘없는 그림’으로 흘러간 가치-기호에 말걸어 보기, 2023.12.22

- 부산비엔날레 2024, 김지평 (2024 Busan Biennale, Kim Jipyeong)