Choe Sooryeon (b. 1986) observes the

aspects of so-called "Oriental-style" imagery and how it is consumed,

reflecting these observations in her paintings. To do so, she collects

traditional cliché images shared across Northeast Asia from classic Korean and

Chinese films. Based on these images, her paintings reveal themes of sorrow,

femininity, disconnection from reality, inner Orientalism, doubt, ignorance,

and absurdity.

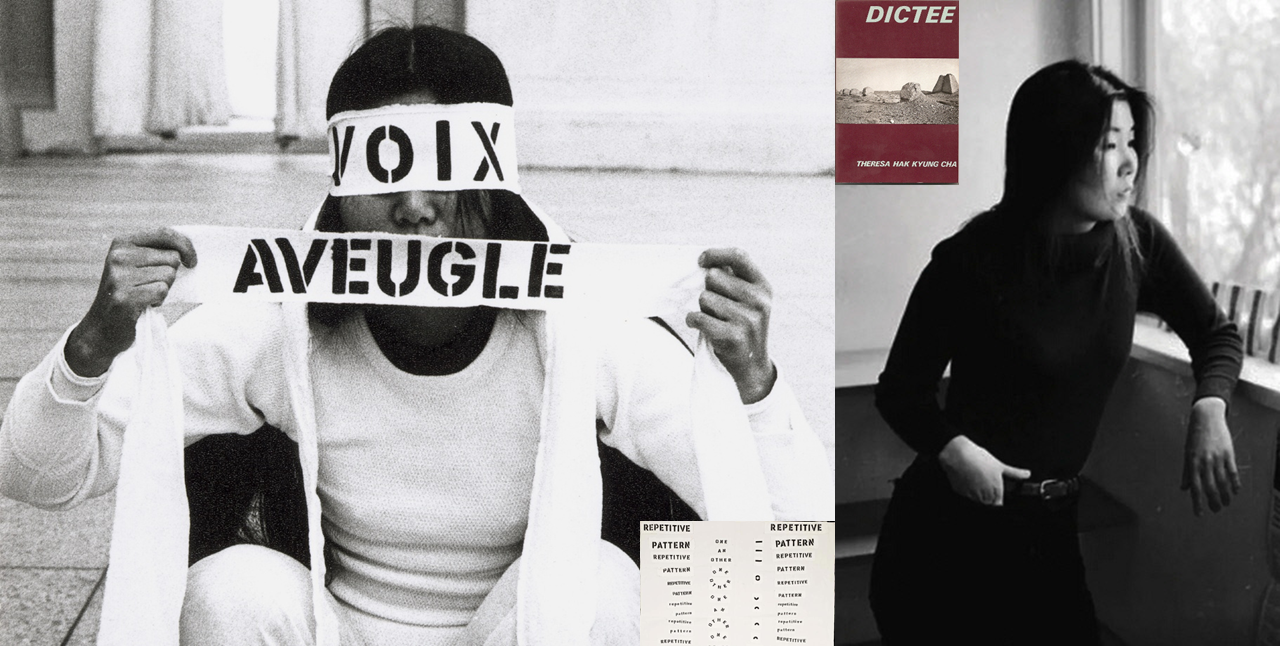

Choe Sooryeon, Eight Seonnyeos (Celestial Maidens), 2013 ©Choe Sooryeon

The artist's interest in classical Eastern

imagery stems from her awareness that her generation’s uncritical perception of

so-called "Oriental-style" or "Orientalist images" is not

so different from the Western gaze. Choe reflects on the background of this

phenomenon, closely examining the transformations, distortions, and repetitions

that occur as these images are reproduced in contemporary contexts. Through

this process, she aims to confront the present reality.

Starting in 2013 with paintings of eerie

mannequins dressed in traditional attire, she has since depicted scenes from

shamanistic rituals, Korea’s new religious movements, historical dramas, and

traditional ceremonies—images that are somewhat strange or comical yet possess

a certain archaic aesthetic. Among the traditional images consumed in modern

events and media, she selects those that are not concrete representations but

rather consumed purely as an atmosphere, using them as the subjects of her work.

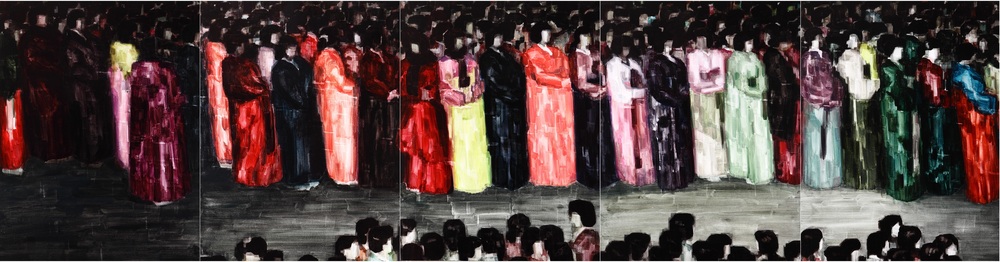

Choe Sooryeon,

Great believer, 2014 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Great believer, 2014 ©Choe SooryeonChoe Sooryeon collects low-resolution

images captured from photographs or videos taken by others. She then removes

certain unnecessary elements and transfers them onto the canvas with minimal

alteration. The images in her paintings appear ambiguous, characterized by translucent

brushstrokes and the coarse texture of the canvas, emphasizing the painterly

qualities of her work.

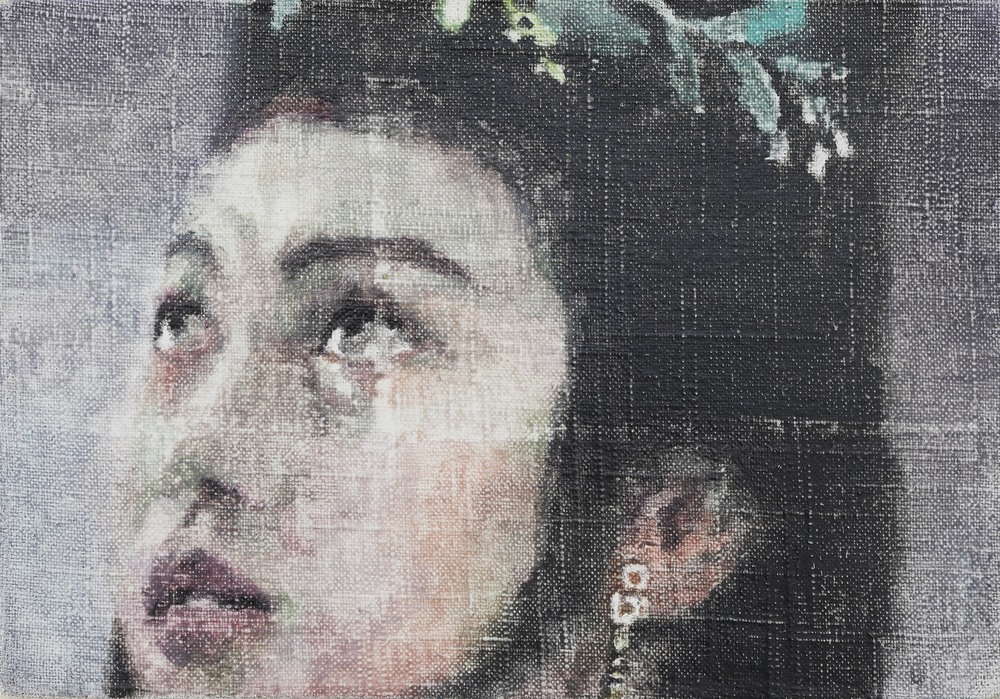

Choe Sooryeon,

懲治 (Deposed Queen Yun), 2016 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

懲治 (Deposed Queen Yun), 2016 ©Choe SooryeonThe artist remains committed to traditional

painting materials. She personally prepares her canvases by treating linen or

hemp with animal glue, creating a surface suited to her practice. Using oil

paint mixed with a high proportion of medium to enhance transparency, she works

quickly in a single layer without revisions or overlaps.

As a final step, she applies oil over the

painting, a process that causes the brushstrokes to blur and partially erase,

leaving behind faint, hazy marks across the surface. These traces play a

crucial role in reducing the illusionistic quality of the image, emphasizing

the materiality of the painting.

Choe Sooryeon,

Seonnyeo (Celestial Maiden), 2017 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Seonnyeo (Celestial Maiden), 2017 ©Choe SooryeonChoe Sooryeon’s ‘Seonnyeo (Celestial

Maiden)’ series, which began in 2017, is an extension of her 2013 mannequin

painting Eight Seonnyeos (Celestial Maidens). In her earlier

work, the mannequins were arbitrarily named based on the colors of their

garments, with titles such as "Sea King" (龍王)

or "Jade Emperor" (玉皇上帝), while the female

mannequins were labeled as “Seonnyeo” (celestial maidens).

In East Asian cultural contexts, Seonnyeo

is often imagined as a young, beautiful woman dressed in flowing traditional

garments. However, in this series, the artist moves away from such idealized

depictions and instead portrays Seonnyeo as a real, tangible person.

Choe Sooryeon,

Seonnyeo (Celestial Maiden), 2017 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Seonnyeo (Celestial Maiden), 2017 ©Choe SooryeonIn this series, the artist primarily

depicts ordinary middle-aged Korean women dressed as Seonnyeo for local

festivals and events, focusing on those with bored or somber expressions. These

celestial maidens, with their strikingly unremarkable faces, subvert

conventional expectations, evoking a sense of estrangement and

peculiarity.

Just as Seonnyeo often play supporting

roles in classical narratives, they continue to serve a secondary function in

contemporary events, appearing as decorative figures while men perform the main

rituals. Acknowledging this dynamic, the artist reinterprets the image of

Seonnyeo—not as an ornament created for someone else's purpose, but as an

ordinary person with an individual presence.

Choe Sooryeon,

Carefree women, 2021 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Carefree women, 2021 ©Choe SooryeonIn contrast to the ‘Seonnyeo’ series, which

portrays real individuals, her ‘Carefree women’ series, begun in 2019, depicts

fictional female characters from films and dramas. The imagery in ‘Carefree

women’ is largely based on the sorrowful female figures frequently seen in

Chinese films and television dramas from the 1980s and 1990s.

Regarding this series, Choe notes that it

emerged from her ambivalence toward the consumption of "Oriental-style

beautiful women" imagery, including Seonnyeo. While she critically

examines the way such images are consumed, she also confronts her own

contradictory desire to paint these familiar clichés.

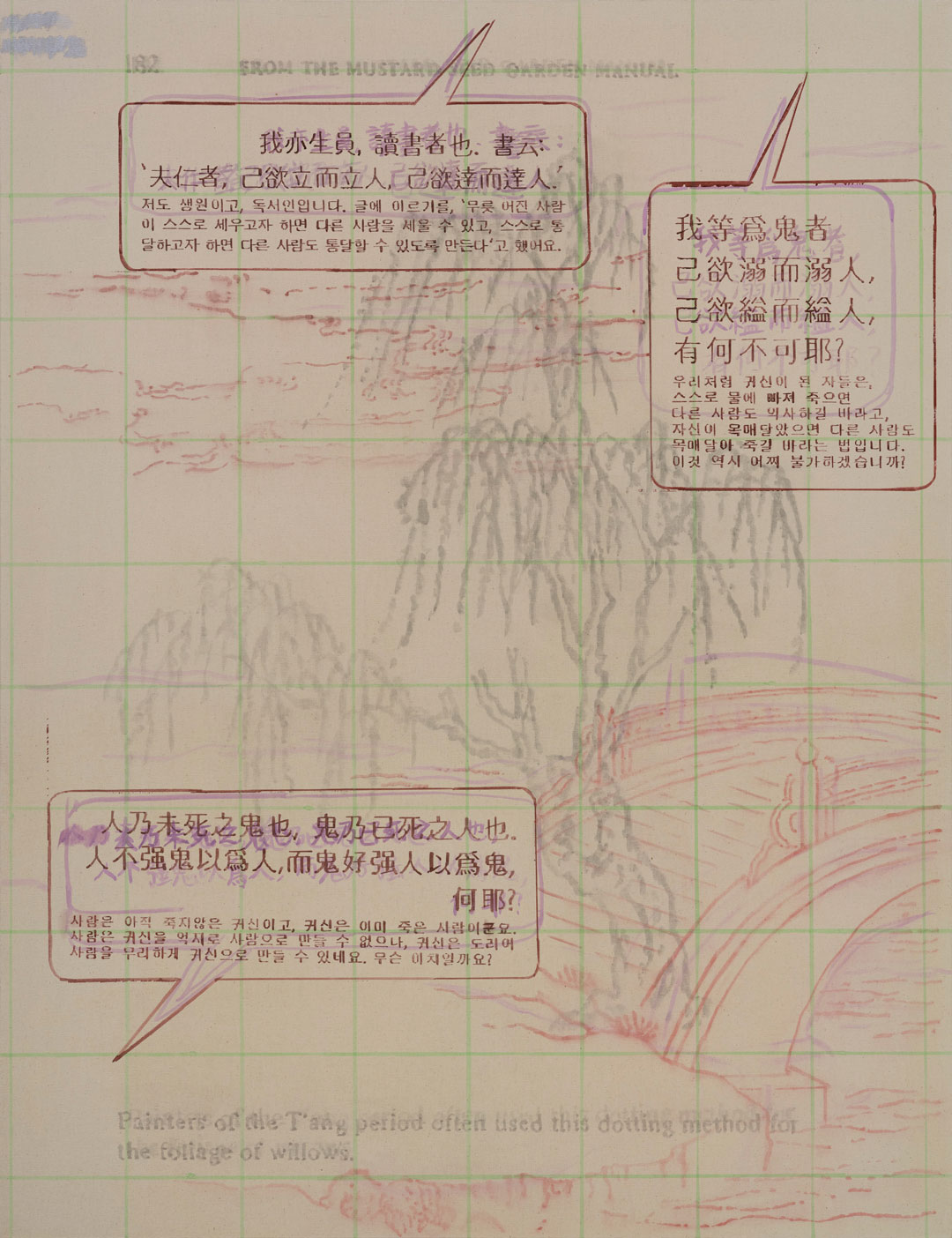

Choe Sooryeon,

Such a ghost would be great. Please do not forsake them., 2022

©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Such a ghost would be great. Please do not forsake them., 2022

©Choe SooryeonChoe Sooryeon also collected lines about

ghosts from Taoist and supernatural films popular in China and Hong Kong during

the 1980s and 1990s, particularly those in which ghosts speak as direct

narrators or interlocutors. Unlike the nostalgic and idyllic imagery often

associated with the past, these lines reflect a worldview rooted in moral

retribution, tinged with pessimism and tragedy.

The artist sees these archaic

phrases—though seemingly obsolete—as still loosely or intimately connected to

the absurdities of contemporary reality. Since she is not fluent in Chinese

characters, she specifically selected scenes where English subtitles were

provided, even retaining awkward translations when they appeared. Additionally,

she sometimes added phonetic annotations to certain Chinese characters in her

works, reflecting the linguistic environment of her generation.

Choe Sooryeon,

Sutra Copying for the Hangul Generation (The Principle of Ghosts),

2022 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Sutra Copying for the Hangul Generation (The Principle of Ghosts),

2022 ©Choe SooryeonIn addition, Choe Sooryeon created a

transcription series tailored for a generation more familiar with Hangul than

Chinese characters. While translating and comparing texts collected from

classical folklore and films, she incorporated gestures of "studying"

into her work—akin to a beginner refining their strokes in traditional

calligraphy or painting practice.

Unlike conventional transcription, which

typically involves practicing beautiful and uplifting phrases, her ‘Sutra

Copying for the Hangul Generation’ series features phrases and narratives that

deviate from the moralistic worldview of traditional folklore and films. She

treats large pieces of muslin cloth as oversized calligraphy paper, writing,

striking through, and refining the text with a light and experimental

approach—subverting the disciplined attitude typically associated with

traditional calligraphy practice.

Installation view

of 《Drawing in the Fog》 (Sansumunhwa, 2020) ©Choe

Sooryeon

Installation view

of 《Drawing in the Fog》 (Sansumunhwa, 2020) ©Choe

SooryeonThese transcription works were also created

in the format of propaganda posters. Choe aimed to blend the practical aspect

of propaganda, which conveys specific messages and narratives, with the

familiar aesthetic pleasure derived from Oriental clichés.

To evoke the inherent lightness of this

content, the artist chose formats such as tearable flyers, retro-style slogan

posters, and advertising banners (or drawings intended for their design).

Choe Sooryeon,

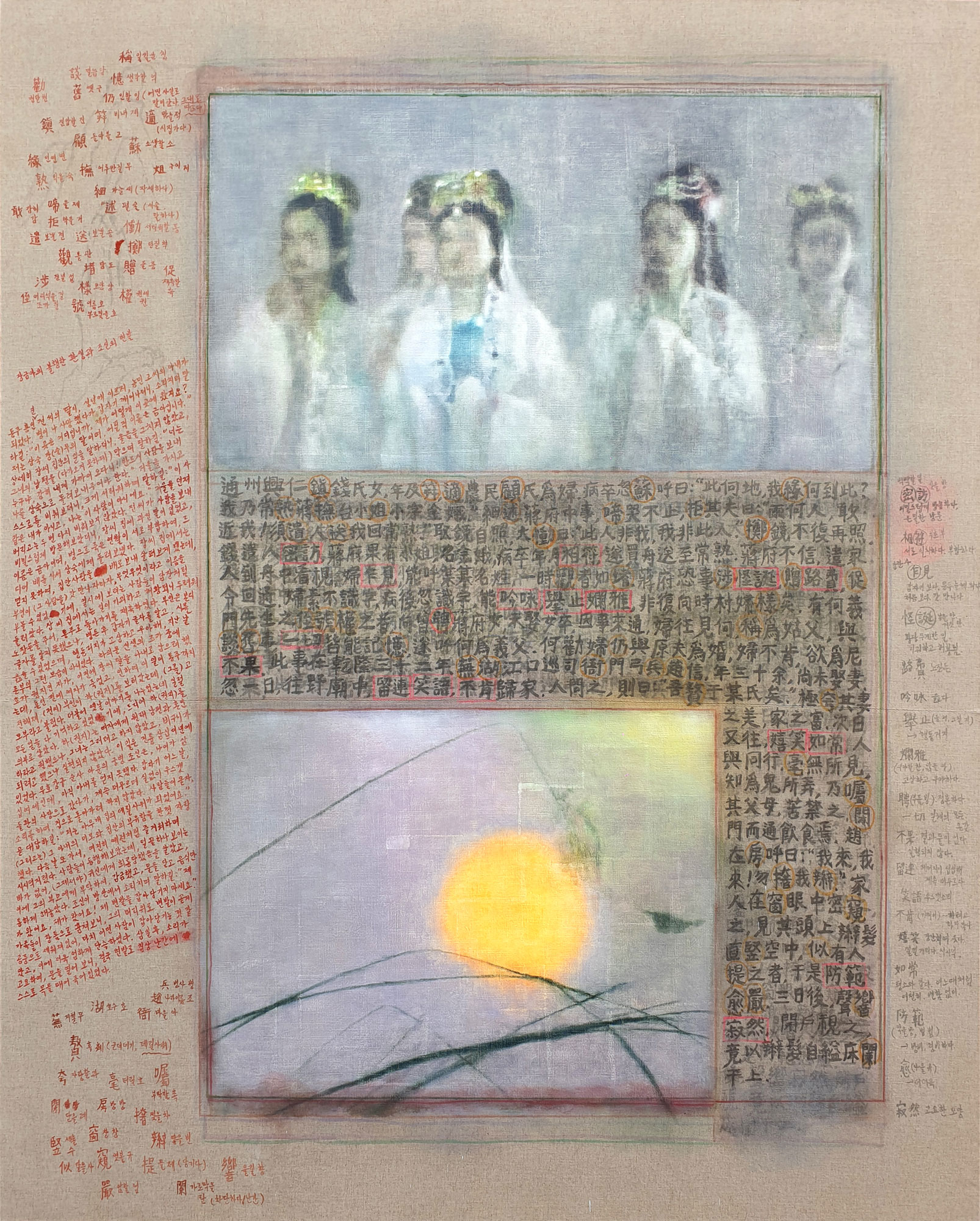

Jiang Jin’e’s unfortunate reincarnation and Zhao Xin’s Queue,

2024 ©Choe Sooryeon

Choe Sooryeon,

Jiang Jin’e’s unfortunate reincarnation and Zhao Xin’s Queue,

2024 ©Choe SooryeonChoe Sooryeon’s recent work Jiang

Jin’e’s Unfortunate Reincarnation and Zhao Xin’s Queue (2024) is a

large-scale piece that combines transcription and painting based on classical

folklore. In this work, the artist adopts the format of Islamic illustration

art, where text and image maintain their own distinct realms. The canvas is

structured with the text translated outside the frame, differing from her

previous works.

As can be inferred from the title, this

work connects two different folktales as though they form a single narrative.

Rather than treating each story separately, the artist chose to bring together

tales with a similarly overwhelming sense of despair, thus revealing an aspect

of incomprehensible tragedy itself. The images drawn alongside these stories

were selected as clichéd scenes that could serve as the background for any

narrative.

Choe Sooryeon, Carefree women, 2021 ©Choe Sooryeon

In this way, Choe Sooryeon has continued to recontextualize the myths, legends, ghost stories, and folktales of Northeast Asia, which carry the absurdity and sorrow of reality, beginning with a critical exploration of the reproduction and consumption of ‘oriental’ imagery. Her work may seem to address something classical and traditional, that is, from the 'past', but the artist examines the surrounding contemporary context, depicting the sorrow, doubt, absurdity, and ignorance inherent in her generation and our society today.

"There are so many things in the world

that are unknown, and particularly things that seem unbelievable, but are too

common to ignore. 'How should we view this?' is the main question in my

work." (Choe Sooryeon, BE(ATTITUDE) Interview)

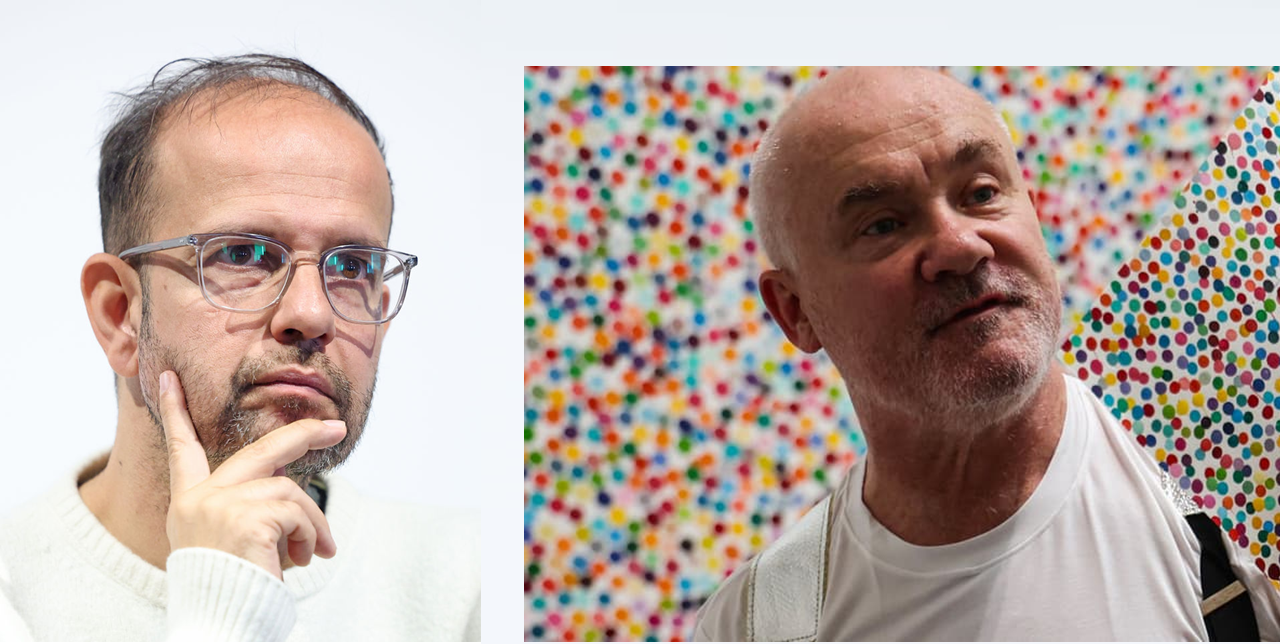

Artist Choe

Sooryeon ©Chongkundang Yesuljisang

Artist Choe

Sooryeon ©Chongkundang YesuljisangChoe Sooryeon majored in painting at Hongik

University and earned a master’s degree in Western painting from Seoul National

University. Her recent major solo exhibitions include 《Hoe

for painted and Hwa for painting》 (Gallery Chosun,

Seoul, 2023), 《Drawing in the Fog》 (Sansumunhwa, Seoul, 2020), 《Pictures for

Use and Pleasure》 (Incheon Art Platform, Incheon,

2020), 《Music from a decaying country》 (Cheongju Art Studio, Cheongju, 2019), and more. She also

participated in two-person show 《Bead & Orchid》

(Chamber, Seoul, 2024).

Choe has also participated in numerous

group exhibitions at institutions such as Gallery Chosun, Gyeonggi Museum of

Modern Art, ARKO Art Center, Museumhead, ThisWeekendRoom, Seoul Museum of Art,

HITE Collection, Insa Art Space, and Art Space Pool. She has been part of

residency programs at Studio Whiteblock (Cheonan, 2022-24), Incheon Art

Platform (Incheon, 2020-2021), Factory of Contemporary Arts in Palbok (Jeonju,

2019), and Cheongju Art Studio (Cheongju, 2018).

She received the 2020 Chongkundang

Yesuljisang, and her works are currently housed in the collections of the Seoul

Museum of Art, Seoul National University Museum of Art, and the MMCA Art Bank.

References

- 최수련, Choe Sooryeon (Artist Website)

- 인천문화통신 3.0, 최수련 인터뷰, 2020.07.22 (IFACNEWS 3.0, Choe Sooryeon Interview, 2020.07.22)

- 인천아트플랫폼, 최수련 (Incheon Art Platform, Choe Sooryeon)

- 인천아트플랫폼, 2020 창제작 발표 프로젝트 3. 최수련 개인전, 《Pictures for Use and Pleasure》 (Incheon Art Platform, Project Support Program 2020 3. Choe Sooryeon Solo Exhibition, 《Pictures for Use and Pleasure》)

- 갤러리조선, ‘한글세대를 위한 필사’ 연작 (Gallery Chosun, ‘Sutra Copying for the Hangul Generation’ series)

- 비애티튜드, 무용한 고군분투 혹은 지극한 사랑