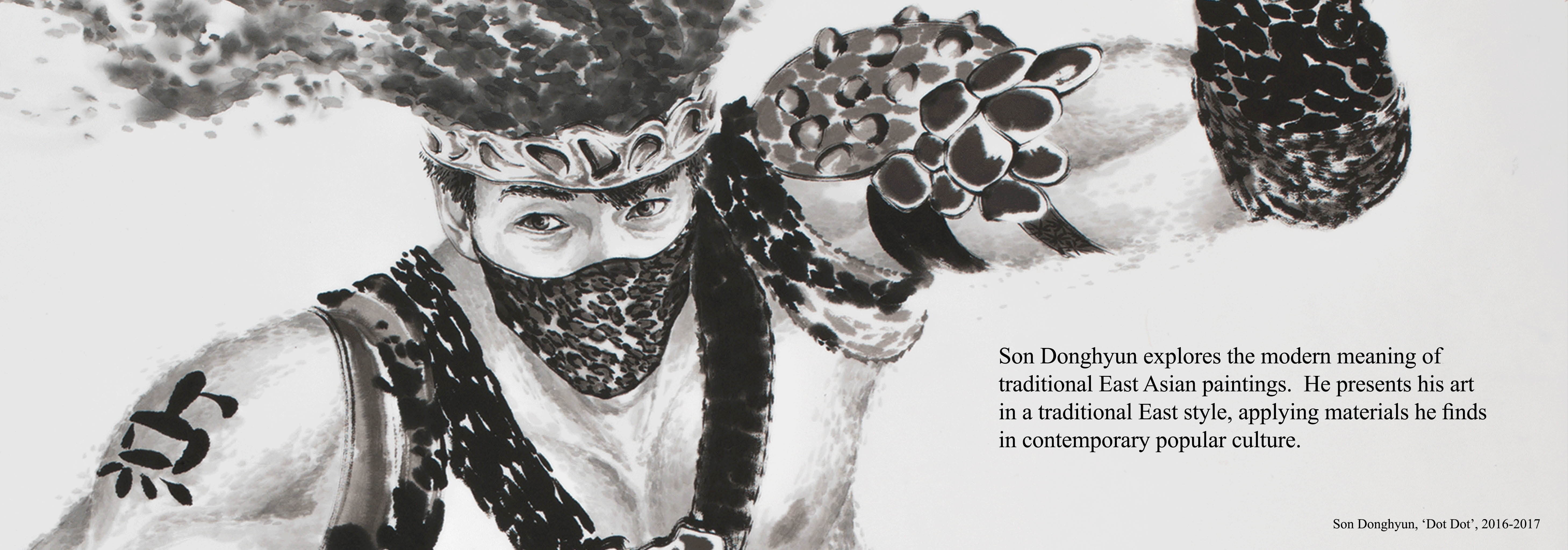

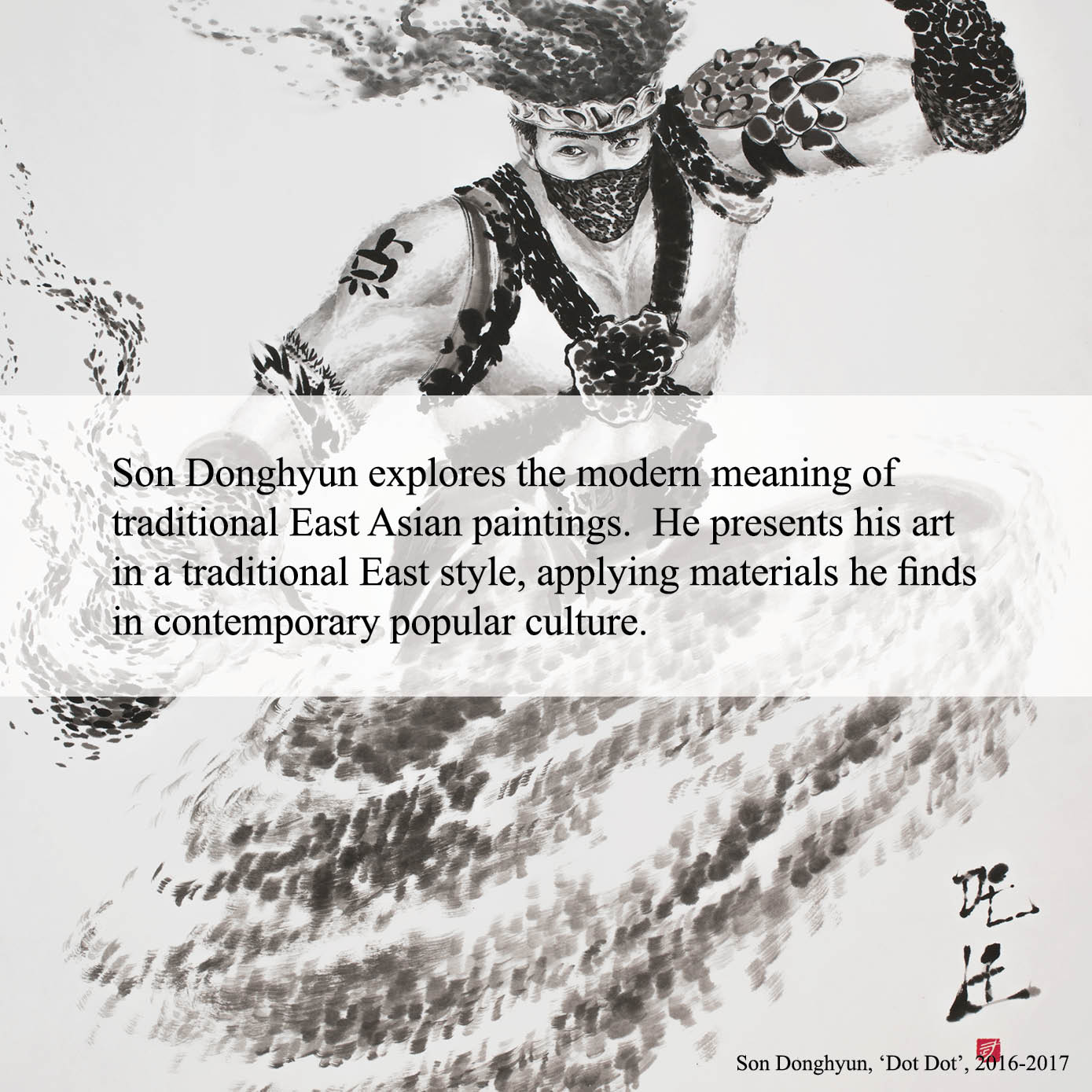

Perhaps it was the

most natural flow of thought. I was thinking of his work all throughout

watching the movie Deadpool. In Deadpool, there is a protagonist whose

actions break the conventional stereotypes, constantly making jokes with

various references. The cartoon-like expressions that playfully interrupt

significant scenes were also reminiscent of his art. X-Men characters appeared on the screen as supporting roles, and

pop music of the 1970s and 80s made its way into the movie. As such, non-novel

cultures were mixed into the production of a new movie. Looking anew at

something with nothing new to it. This is a fitting description for Donghyun Son’s

art. Son creates new scenes by matching existing characters in the form of Korean

traditional painting, a form that is deemed old. And now I have been given the

chance to yet again elaborate.

There are many ways

to read the paintings of this still young artist that stood at the center of

attention upon university graduation and has since built a sturdy career

through repeated verifications. Such a great variety of narratives from diverse

perspectives are possible that it is difficult to select which one aspect to

focus on. He is a novel artist of Korean traditional painting

that has brought forth an original alternative amidst the crisis of Korean

painting. I could discuss a Korean style pop art (now that we even have a set

terminology of K-POP) in the genealogy of pop art. He brought portrait back to

the center of attention, a genre that has been rather marginalized in the

context of contemporary art. Most arresting for me as a writer is to discuss

him in terms of generation. Born in the 1980s and surviving the today, he is of

a generation that embraces a vast variety of symptoms and dons various names,

from the “0.88 million KRW generation” to the “N-forfeiting generation” that

faces even harsher conditions than the initial 3-forfeiting, 5-forfeiting,

7-forfeiting generations and has now given up countless things of life. The

generation represented by the artist, still in his 30s at the point of this

paper written in 2016, has had many ups and downs and has many stories to tell.

This generation was first-handedly introduced to various systems such as the

television, Internet, smartphone, and online social networking services. Thus

familiar with the new systems, the generation stood at the forefront of

building networks with the outside world based on the technology that was as

natural to them as their limbs. Son’s art is also appropriate for articulating

the effects of this surprising new culture. In fact, fully loaded with such

content, Son’s works themselves do not represent any technological advancement

by themselves. Rather, his works are closer to being an endeavor of pulling out

the forgotten tradition back into the present. However, the global reference

materials he appropriates would not have been possible without the help of the

Internet, and such methodology requires the generation’s sense as a global

citizen in regards to television, film, and music. It is thus sufficiently

worthwhile to discuss him in terms of the Internet generation. His art could

also be read as a satirical manifestation of a nationalism resisting against

cultural imperialism and the American hegemony. In a similar context, his art

is also a convenient example through which to explain the hybridity often

discussed in post-colonialism. There is ample value in diligently tracing and

summarizing in a textbook-like manner the process of change in the artist’s

oeuvre that has constantly developed over a period of more than ten years.

Looking back, a majority of critiques on his art have discussed him as a

generational symptom, and many have also interpreted his work as pop art and fusion

Korean traditional painting. Perhaps the most appropriate way to discuss his

art would be to talk of all this. I will thus seek to process his art through

various nets and filters, ultimately drawing a map.

Donghyun Son

entered Seoul National University as an Oriental painting major in 1998. In

2004, as an undergraduate, he started producing a unique grammar with his Portrait of the Hero, Mr. Batman, a

portrait of the American superhero Batman in Korean traditional painting

technique. In 2005, his second and third versions of Portrait of the Hero, Mr. Batman conveyed more elaborate and dense

descriptions. The 2005 was the monumental year he started to paint portraits in

full earnest. From the portrayal of Star

Wars characters in Portrait of the

Space Warrior, Mr. Yoda, Portrait of

the Droids, R2D2 and C3PO, and Portrait

of the Sith Lord, Mr. Darth Vader, to the portrayal of Shrek and Toy Story

characters in Portrait of the Dynamic

Duo, Shrek and Donkey, or Portrait of

Mr. Woody, and Portrait of Mr. Buzz

Lightyear, and also the portrayal of the McDonald’s mascot Ronald McDonald

in Portrait of Mr. Ronald Mcdonald –

all were painted within one year. And these pieces were brought together under

the title Pop-Icon:波狎芽益混 in 2006 for the first solo exhibition at Art Space Hue.

The history of portraits is very long, safe to say that it starts with the

birth of art. Ever since civilization and power were first introduced into the

history of man, portraits were produced as a means of documenting the powerful

and their families. From da Vinci to Rembrandt, Whistler, Repin, and Sargent,

there are many familiar and famous portrait painters. In this text, however, I

seek to locate the position of Son’s unique portraits in the context of contemporary

art. For Donghyun Son, born in 1980, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) is just one

century apart in history. Let us start from Picasso, who developed his art

through various technical and formal experiments with numerous women as the

object of his portraits. Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein in 1906 was

produced right before he surprised the world in 1907 with his Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. By

incorporating in painting the methodology of stiff description that seems as if

carved out of wood and inspired by African masks, it formally stays on the starting

point of Cubism and at the same time reveals the sturdy character of the

figure. Conveying the character of the portrait’s figure through exploration of

new form coincides with the nature of Son’s portraits. Son brings characters

from Western culture and fantasy, those unfit for the medium of Korean

traditional painting, into the form of portraits and also manifests the

spirituality of portraits as well. This is in fact the concept of jeonshinsajo (傳神寫照) that is greatly emphasized in East Asian traditional Art, first coined by

portrait painter Gu Kaizhi (顧愷之)[i]

of the Dongjin (東晋)(317-419) dynasty

to convey the task of reaching beyond a mere representation of form and seeking

to paint even the mind. Gu argued that the specific background of each portrait

should be employed in conveying the object’s mind, and Son uses each

character’s representative props or costume, or even the transformation process

of the character’s appearance itself to portray the character’s personality.

Translating into Korean traditional paintings the portraits of characters who

have already succeeded in manifesting their virtual characters in films and

expressing their identities not only through their own bodies but also related

props, Son could very effectively manifest the jeonshinsajo. In fact, most portraits in modern art cannot but be jeonshinsajo not so much because of

their realistic portrayals, but because they focus on expressing the figure’s

sentiments. Alice Neel (1900-1984) founded her practice upon intimate

relationships with her objects and also sought portraits that convey even the

inner hearts of the figures. Come to think of it, who could be better at

conveying the inner image of the object than Lucian Freud (1922-2011)? Setting

aside the fact that his grandfather was the grand psychologist Sigmund Freud,

the painter’s endeavor to portray the human’s sentiments and character through

the expression of body and skin is clearly evident on the canvas. Somewhat

coeval American painters Larry Rivers (1923-2002) and Alex Katz (1927-) also

come to mind. Their styles are very different, but they can be aligned in the

context of Western jeonshinsajo in

that they painted numerous portraits of their friends and thus revealed their

own relationships with the objects in the paintings.

And then Andy Warhol (1928-1978) suddenly pops out. Our young art student

in Korea inherited from this Pop Art founder the methodology of borrowing the

fame of superstars. Leaning on the portraits of the most famous people of the

times such as Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy, Elvis Presley, or Elizabeth

Taylor, Warhol became as famous as any one of them. On top of that, the beloved

Campbell Soup and Coca-Cola are also popular items that Warhol is indebted to.

Son’s methodology of appointing familiar models such as Michael Jackson, Shrek,

and Superman, or of bringing Coca-Cola and Nike logos into paintings all stem

from Warhol. The Logotype series that

the artist concentrated on in 2006 puts at its forefront the familiar logos of

various brands that were borne not out of cultural purposes, but as commercial

means. These pieces that accentuate the global brands of Adidas, Starbucks,

Coca-Cola, Nike, McDonald’s, and Marlboro are very amusing to observe in

detail. Logotype-Coca-Cola is a

canvas filled with the Coca-Cola logo in a cursive font. Inside the logo is an

array of elaborate and witty images that don the disguise of pattern. Referring

to the fact that Santa Claus is a character fabricated for the advertisement of

Coca-Cola, he painted a scene of Santa Claus delivering presents while carrying

a Coca-Cola, and also borrowed the famous image of a polar bear drinking Coca-Cola.

Logotype-Marlboro also portrays the

stereotyped image of the Marlboro Man and the image of characters dressed in

Chinese traditional clothes and hairstyles while smoking and wearing Western

boots and Cowboy hats. Logotype-Nike

and Logotype-Adidas are also adorned

with patterns of people wearing Nike or Adidas, and related sportsmen images.

Slogans that each brand advertises, such as “Just Do It” and “Impossible is

Nothing”, are also decorated as patterns while each alphabet is placed inside a

round badge. By actively bringing popular consumer items into the frame of Korean painting, Son also breaks down the

boundary between image and text. As with calligraphy where the letters

themselves become the artwork, or the literati paintings where text and image

coexist inside one screen, which were favored by the gentry who had regarded

the talents of producing poetry and painting as refinement, the tradition of East

Asian traditional Art does not clearly

distinguish image and text. Son’s Logotype

series combines the forms of calligraphy and genre painting, and further mixes

Western brands and mass media in its contents, flaunting the painter’s unique

sense of editing. In the West, pop artist Robert Indiana (1928-), a coeval of

Andy Warhol, had also embraced text as image. The portraits produced by Mel

Ramos (1935-) and Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004), a mix of advertisement and

pornography, were also attempts by Warhol’s coevals to appropriate both

capitalism and Warhol at the same time. As such, it is effortlessly enjoyable

to transcend all temporal boundaries in reading the cultural and social

references of both the East and the West through the productions of this young

man that majored in Oriental painting in Korea.

There were also artists using photography in producing the portraits of

their generation. Cindy Sherman (1954-) and Nan Goldin (1953-) are such

examples. Sherman’s photos in which the artist played various roles to reveal

the cultural stereotypes of the generation, and Goldin’s photos that capture

the everyday of her friends from a very close distance. Only the medium has

changed, while still serving the traditional role of portraits. Nikki S. Lee

(1970-) would be their descendent, penetrating the stereotypes of each

nationality and capturing natural portraits. Stereotyping is in fact the

imperialist tactic for seizing cultural and political hegemony. As Edward Said

had pointed out, they produce a stereotype that the Oriental, the East, is

sentimental, mystic, and feminine to contrast the opposing Western society as

rational and masculine. They designate “the other”, and start stereotyping and

otherizing as a means of rationalizing their operation of empires. Therefore,

the very basic in discussing post-colonialism is to break free of that

standardized thinking. For this incredibly talented painter born in a small

country of the Far East, a country that also bears the history of colonization,

to extract the innate traits of foreign super heroes, pop stars, or cartoon

characters and paint as closest as possible to the original image is to push

the standardized ideas to their extreme. Here, it is worthwhile to study why it

is meaningful to translate the standardized ideas of cartoons and films into

painting. I should mention here the point where the two stereotypes produced by

imperialists collide one another. And the crash that occurs at that point where

the product of cultural imperialists, the Hollywood characters or the grand

heroes unlikely to exist in reality, are reproduced into the unique culture (Korean

traditional painting) of “the other” that is regarded as feminine and savage.

Under colonial rule, the ruler orders that the colonized should “follow the

lead of the ruler, but only to be similar, and never should be completely

same”. The colonized is ordered to conform to the ruler and become similar, but

only to the point of being different enough to be distinguished from the ruler.

This hybridity, a tactic through which to signify that the colonized shall always

remain as the crossbreed, is a bit specially interpreted in Son’s works. For

instance, as Homi K. Bhabha had argued, it creates not the distinction between

the self and the other or between one’s own culture and the other’s culture,

but produces the “borderline” or the “in-between” space. To speak from the

point of post-colonialism, it transcends the dichotomous distinction between

the ruler and the colonized, and designates a third space. This does not mean

to awkwardly follow the major, but to stand in between the major and the minor

to be able to refer to each aspect and yet create something completely new. It

is under this same context that Son’s art mixes various classes and cultural

devices to penetrate the in-between space.

In the meanwhile,

the works of Jim Shaw (1952-) and Mike Kelly (1954-2012) bear resemblance to

those of Son in a way different from that of portrait painters. These two

artists, born around 1950, presented works in which they added their personal

tastes onto various American cultures encompassing comic books, album covers,

magazines, religion, post-punk politics, and black humor. Their productions don

various forms from installation to painting and video, and while they are

diligent compositions of cultural references and may seem similar to secondary

productions, judging from the point of contemporary art grammar, they merely

take on the methodology of simple appropriation. Son’s work is just like this.

Because he brings in the images of characters and famous people that he has perfectly

interpreted through his own style, no one can mention secondary production or

plagiarism. The only difference between Shaw or Kelly and Son is that while the

former appropriate their domestic contents, Son employs foreign contents that

have been imported into his domain.

Palimpsest is a

term stemming from the ancient way of writing when there was no paper and

people made new books by erasing the preexisting letters and rewriting on

parchment. In that the cultural identity of colonies cannot start from a white

slate and is only rewritten from the state of being stained with various

products of imperialism, the historical documentation of colonies is likened to

palimpsest. Now it also signifies the comprehensive contents of multi-layered

meanings. When Son becomes an active subject and not a hybrid in embracing the

Western elements, -- that is, when he paints characters of Western culture on Korean

Mulberry paper -- there is already an

accumulation of such a variety of layers, from the paper to the character, that

it cannot be simply regarded as mere “painting on paper”. Among the

post-colonial resistance discourses is the “Writing Back” tactic through which

the colonized becomes the subject and rewrites English literature classics.

Nancy Rawles’ novel My Jim was a

rewritten version of Mark Twain’s Adventures

of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of a black woman with Africa as

the background. If I were to discuss Son’s methodology within the context of

post-colonial theory, I would say that it is closest to this “Writing Back”.

But it is not a perfect match in that while the speaker, technique, and

background are autonomous, the protagonists of the canvases are still the

products of imperialism. As mentioned before, however, Son’s work is attractive

because it does not perfectly conform to any given frame. He has succeeded in

creating an exquisite in-between space that does not belong anywhere and yet

seems to fashionably fit anywhere.

After the advent of the aforementioned group of photographers, we saw a new

group of portrait painters of yet another form. John Currin (1962-) humorously

conveys glamorous blond women through exaggeration and distorted editing as the

likes of cartoons to expose the vulgar taste of white men. As a device through

which to ridicule the masculine perspective from the perspective of women, Lisa

Yuskavage (1962-) employs a portrait of women that is exaggerated and distorted

to the opposite sense of Currin’s, but also embraces very cartoon-like senses.

In fact, Korean traditional painting shares more common grounds in terms of

material with cartoons that are expressed through pencil, pen, and water paint

on paper than with oil painting on canvas. The attempt and eventual success of

hauling the vulgar or B-class culture (as cartoon and third-rate magazines are

deemed as a group) into high culture were shared among this group of portrait

painters. In a way different from that of Warhol’s, there is a way the icons of

pop culture and B-class culture that Son appropriates correspond with this

group of artists’ models. Although I hesitate to repeat, because the characters

that Son puts forth as his models are in many cases the products of cultural

imperialism albeit being classified as B-class, Son’s art produces various

complicated contexts for other nations who also import that culture.

From 2005 to 2007, Son painted two to three animal portraits each year. I

say animal portraits, but they are in fact all animal characters from

animations. Designating the Bugs Bunny and Sylvester from the 2D animation Looney Tunes as the models, Rabbit and Rabbit and Sparrow were produced in 2005. In 2006, he painted Road

Runner and Wile E. Coyote in Bird and Dog

under Bamboo, and Daffy Duck and its baby in Birds. In 2007, the tiger model Tony for the cornflakes brand

Kellogg’s was portrayed in Tiger under

Pine tree, and two Toucan Sams from Froot Loops were painted in Two Magpies. One significant trait of

this group of canvases portraying the animal characters is that each of their

characteristic background is also introduced in the screen. Tony stands robust

under a pine tree wearing a red scarf, while Toucan Sam sits on a tree along

the ridge. Wile E. Coyote hides behind a rock, and Sylvester wickedly waits for

Tweety to fall from the branch into his hands. When we say that it is possible

to classify culture as high and low, the animations that children enjoy are deemed

bereft of depth in contents and regarded as the low culture. Son’s methodology

is to mix this low culture with the literati painting of the East’s high

culture that was greatly appreciated by the gentry. If we take one step further,

Korean traditional painting, now an object of no interest regardless of class,

will be classified as the non-major while the cartoons, still greatly loved by

many, is deemed the major. We cannot avoid the discomfort and awkwardness that

arise when transcending the different layers of countries, times, cultures, and

classes. It also points out the reality in which the cultures are ranked not by

the evaluation of each culture’s value itself, but accordingly to the hegemony

of the times. This interesting conflict between culture and class is, if I were

to make a figure of speech, like Disney’s Mickey Mouse appearing on Im

Kwon-taek’s[ii] film. To use this metaphor in reverse, it is as if

Dooly the Little Dinosaur[iii] or Run Hani[iv] were portrayed in traditional Western portraits

painted in the grand manner of Ingre and David.

Frantz Fanon, who

had stood at the forefront of the third world’s anti-imperialist movements and

led the independence of Algeria, said “I resolved, since it was impossible for

me to get away from an inborn complex, to assert myself as a black man. Since the

other hesitated to recognize me, there remained only one solution: to make myself

known.” And a new trend of black portraits stemming from such thoughts was

brought to attention. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (1977-) creates characters in

literature that have black people as the protagonist and paints their

portraits. Kehinde Wiley (1977-) puts common black people inside the

composition of portraits of heroes, such as that of Napoleon, and questions the

function of portraits. As such, Yiadom-Boakye and Wiley put their

minority-ness, or to borrow Fanon’s expression, their “complex”, at the

forefront and attempt to reach beyond merely “coveting the mainstream” and

instead “overcome the mainstream”. Then what is it that Son seeks to achieve in

painting the portraits of American mainstream characters? Is it to “explicitly

look up to the mainstream”, to humorously flaunt cultural sycophancy? Furthermore,

he portrays the mainstream through Korean traditional painting techniques, the

perfectly non-mainstream in the contemporary art scene. This is not all. We can

also see that he puts quite some interest and focus on the villains and

supporting roles as well. Apparently not insisting only on the mainstream, even

the superhero films and animations he refers to are in fact closer to the

subculture with mania fans. Thus, although the methodology and final products

are different, Son’s tactics are similar to those of Yiadom-Boakye and Wiley in

that they subtly mix the mainstream and the non-mainstream. Son has said that

he is more interested in history than in specific phenomena. “When introducing

an image, it is to reveal the history.” Then why is the history that the artist

mentions portrayed and conveyed through the image of heroes created by

foreigners, founded upon foreign films and animation characters, and in

particular the American cultural imperialism? The question also remains as to

why it has to be American culture. This could be a reflection of the artist’s

personal taste favoring hip hop and American culture, and this is also a

reflection of the reality that Korean culture is consistently and greatly

exposed to American culture. For an individual who grew up in Korea after 1980

to speak of his relations with the media, it is difficult to not mention

Hollywood movies or their expansions, the animations of DreamWorks or Pixar and

Marvel Comics. We need to understand the peculiar cultural colonization that

requires us to speak of American culture in order to discuss Korean culture.

This is also why it is necessary to tediously and continuously explain the

works in relation to postcolonial discourse.

At his solo

exhibition King in 2008 at Gallery 2,

Son pertinaciously tracks the transformation process of Michael Jackson’s

appearance since his debut. Painted in the form of traditional portraits of

Kings, there were about 40 Michael Jacksons sitting on the traditional Korean

throne. Like Portrait of the King (01 got

to be there), Portrait of the King

(22 man in the mirror), and Portrait

of the King (33 scream), each piece in the series was numbered and labeled

the title of the album that Jackson released around the time he looked like how

he is portrayed in the portrait. The young Michael Jackson was first seated on a

leopard printed chair, and it was from the 1989 when he earned the name “King

of Pop” that he sits on the red throne. From Portrait of the King (26 black or white) to the final Portrait of the King (40 one more chance),

he was never robbed of his throne. The process of the King of Pop’s struggle to

erase his identity as a black man through plastic surgery is clearly conveyed

throughout the 40 chronological portraits. Bhabha had said that under

colonization, mimicry comprises the potential of resistance and overthrow. By

mimicking the ruler, the colonized threatens the authority of the ruler, making

the ruler anxious about the possibility that those mimicking them could

eventually throw a riot. Bhabha had thought that such mimicry and its symbolic

resistance could damage the solidity of imperialism. However, it is worth

looking into what Son has tried to say by tracing this eccentric trajectory of

mimicry by a man who, as someone from the non-mainstream, ascended to the top

of the mainstream and sought to shed of his original identity. It seems that

Son tried to convey the jeonshinsajo

in its true essence, observing the changing faces of a man as he shifts from

the colonized (black man – child – rookie singer) to the ruler (white man –

adult – King of Pop). No other man has ever manifested the process of migration

from the non-mainstream into the mainstream as bluntly as Michael Jackson. And

no other man has willfully changed as successfully as Michael Jackson. Of

course, there would be various judgments on the usage of the term “success”

here. Because Jackson was never away from public attention or popularity, it

would have been easy for Son to acquire the materials of any period he was

interested in. One man’s changing appearance and newly released albums served

as the archive of an era. Tracing the history of the man, we can also follow

the trend of culture through the costumes and appearances donned by the King of

Pop that led the fashion.

In his 2010 solo

exhibition Island at Project Space

SARUBIA, Son introduced his folding screens to the public. Referring to the

list of “10 Best Movie Destructions of New York” selected by the New York

Magazine, he referenced the city smashing scenes of Deep Impact, Armageddon,

and Godzilla, reinterpreting them

from various perspectives and painting them in the form of folding screens – an

eight fold folding screen, composed of eight scenes. Unlike his previous works,

he worked in the form of ink painting bereft of color, and with the intention

to paint landscapes, focused on portraying scenery rather than people.

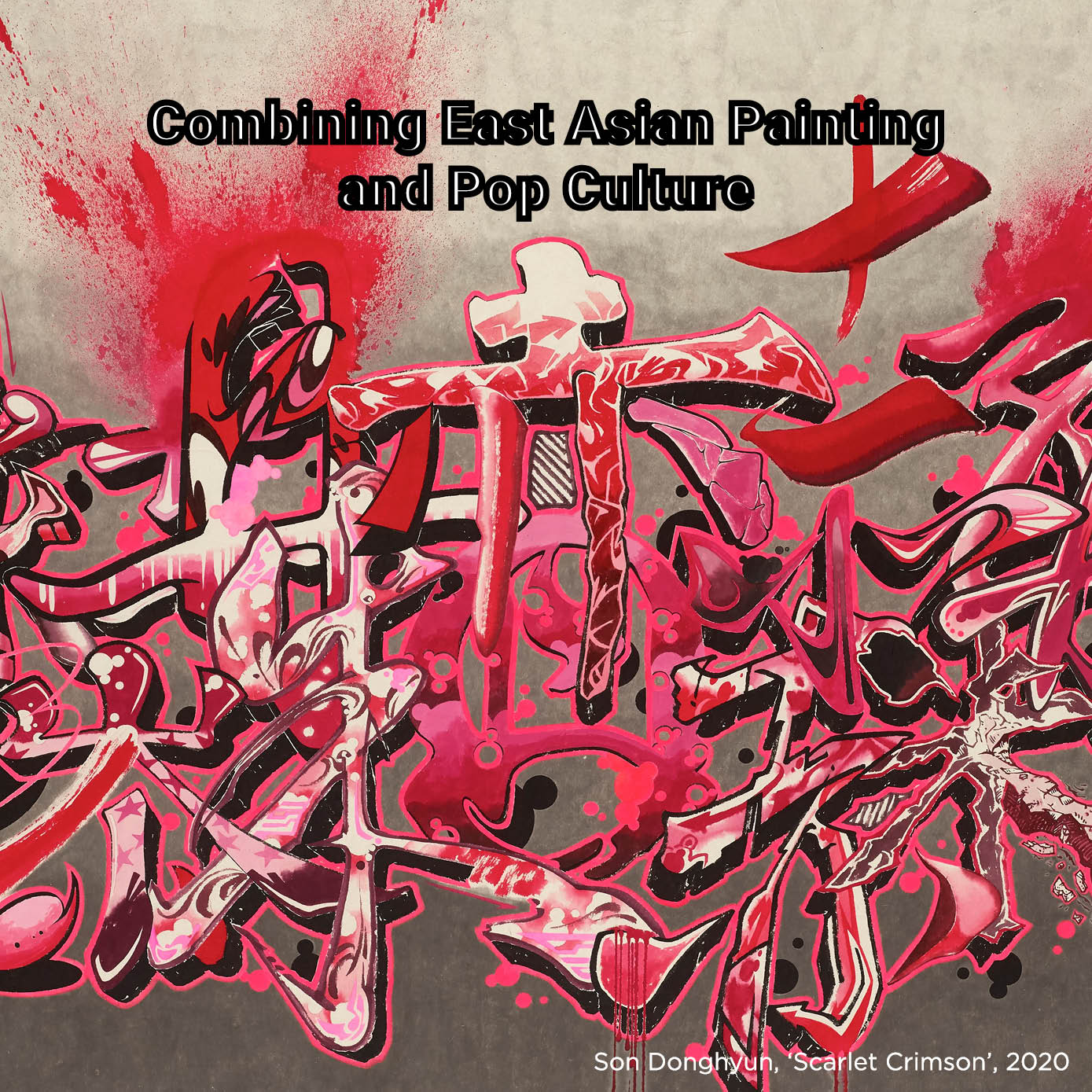

Encompassing all genres of East Asian traditional Art from

portrait and landscape to literati paintings of the gentry and calligraphy, the

artist portrays the material he is most interested in with the medium he is

most comfortable with. At the same time, he is weaving a tight archive of

cultural and art historical narratives, placing himself in a very unique

position with art history. It seems Son’s art itself serves as the hybrid

mutant in this complicated world. While hybridity may embrace a negative nuance

within postcolonial discourses, this hybridity is in fact the character of

Son’s art. If one were to become a mutt, one should stand at the center as the

“super mutt” like the superheroes he paints, and thus be able to counterattack

the ruling power. In fact, mutts have started fighting back a long time ago.

K-POP has reproduced American pop music in Korean style and earned great

popularity within Asia, recently extending its fame throughout America and

Europe too. On a slightly different note, there are also Hollywood movies that explicitly

play the hybridity card, as in the case of Kung

Fu Panda – contents of hybridity that a major Hollywood company produced by

mixing various elements of numerous nations in order to target the entire

world. In a globalized world, there is no limit to transcending boundaries. The

boundary between what is yours and what is mine becomes ambiguous, and clear

perspectives that help discern and characterize within that ambiguity become

precious. This is the point Son’s Korean traditional paintings of Western

contents become valuable.

In his Villain exhibition at Gallery

2 in 2011, Son traces the change in villains throughout the 20 episodes of the 007 series between 1962 and 2002. In

this series of panorama, he categorizes the object of fear that is

characteristic of each period. During the Cold War, a man of Socialist uniform was

the object of fear and the role of signifying the evil went to billionaires or conglomerates

after the success of capitalism. The typicality of the one-eyed villain boss giving

out brutal orders while affectionately petting their pets such as cats or

chameleons was also repeated. The image of evil associated with the North

Korean military or black men dealing drugs is continued to this day. Louis

Althusser has explained the concept of “interpolation”. Each individual that

has been called forth under the ideology of imperialism has to follow the

ideology of imperialism. Here the term imperialism refers to a temporary system

of values that is created to seize the hegemony of a certain group in a certain

period. Althusser speaks of the mechanism of power operated through stereotying

and otherizing, and the ideology of interpolation. For instance, communism is

deemed evil in a society where communism is designated as the other, and each

individual regards communism as evil not through their own judgment but the

hegemony set by imperialism. As such, the source of evil is very political. Villains

are in fact titled as villains not because they have done evil deeds, but as

the product of distinguishing and otherizing.

In 2011, the same year the Villain

exhibition was held, Son also produced the Mask

series of 41 episodes. It was a composition of masks that appear on various

hero narratives. In 2012, he produced around 50 goods, painting various space

shuttles on fans. The From Outer Space

series, collecting 22 outer space characters in one old book, was also produced

in this year. The Robot, a collection

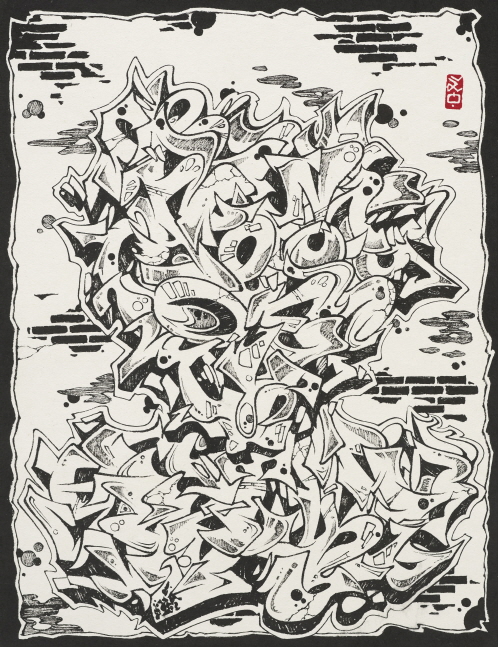

of 22 robots in one old book, was also painted. The artist’s experimentation

outside the conventional form of frame mounting was very active this year. While

bringing change to the appearance of his works through the form of fan and album,

he also obsessed more over goods than on characters, more strongly expressing

his mania for collecting materials. It was the phase of delving deep into one field,

as if an otaku, and producing paintings as the product. In fact, all of Son’s

works are greatly associated with the otaku-like collection of material. In

other words, it could also be described as similar to the attitude of a scholar

collecting material for dissertation. But because his interests lie in maniac

animations and films that the otaku also find interesting, it is better fitting

to call him an otaku. Please forgive my rather radical categorization.

The art of a famous artist that has gained a stable status of fame goes

through a drastic change in 2014. Seemingly completely “post”colonial now, the

artist started creating his own characters. Even the title of the exhibition

held at Willing N Dealing in 2014 was Pine

Tree, hinting at independence. The pine tree that had traditionally

portrayed the dignity of king in “Sun and Moon and Five Peaks”, the fidelity

and integrity of the gentry in “Wintry Days”, chased away the evil with its sacredness

in “Magpie and Tiger”, and signified longevity in “Ten Longevity Symbols”[v],

was reproduced as a mighty superhero by Son. Having cultivated his talent of

creating and mixing to its peak, the artist was partially inspired by the

characteristics of existing superheroes when creating four unique characters: Pine the Great,

Mister High Fidelity, Shaman the Evergreen, Master Knotty Needles. Just as

Cindy Sherman had borrowed the stereotypes of classic films and shot the image

of herself in her early works, and thus earning suspicions of recreating an

existing scene but in fact having created an entirely new scene, Son produced

purely new heroes that seem familiar. In Pine

the Great, the spikey straight lines of the green pines transform into

hair, while the hard skin of the pine tree is already in the pattern of armor.

The curves introduced in Mister High

Fidelity and Shaman the Evergreen

signify the beauty of pine trees that have endured through the harsh winds and

times. Master Knotty Needles portrays

the acute image of a hero, founded upon the sharp leaves of the conifers. Scrolls

created as posters and the front pages of comic books were also on display,

capturing not only these characters but also their opposing villains. The names

of these pine tree characters were written in completely new letters, based on

the Chinese contemporary artist Xu Bing’s creation of Chinese character forms

produced with Roman alphabets. This new form of mixing -- appropriating the

methodologies of contemporary artists such as Sherman and Xu Bing, and creating

his own characters -- is the recent trend of Son’s art. And here, I am yet

again drawn to where Son appropriated Xu Bing’s letters. The image of these alphabets

disguised in the form of Chinese characters implies that the world’s mainstream

letters would have looked very different if China had won the hegemony of world

history. Xu Bing’s philosophy, borrowed from Mao Zedong, to “make the old

things serve the present, make foreign things serve China” seems to represent

Son’s attitude toward art.

When it seemed

there would not be any new changes, this diligent worker that does not stop

updating himself showed yet another evolution at SongEun ArtSpace in 2015. He

produced a portrait series under the name Six

Warriors (六俠), based on “Xie He’s

six principles of Chinese traditional painting” that the painter of the

Southern Qi dynasty (479-502) had presented as the six essentials of landscapes.

Having created new characters based on this representative discourse of East

Asian traditional Art, the series is similar with the Pine Tree exhibition in that it introduces characters created by

the artist. Within this series composed of six warriors, the artist

reinterprets the six principles of painting as the characteristics of martial

specialties possessed by each warrior. For instance, Son painted Master Spirit through a composition of

various energy expressions conventionally used in animations in order to convey

the “spirit resonance”, one of the six principles of painting.

The reference

materials available to Son are Google-like. Ten years ago, I would have

described his global and trans-temporal appropriation of knowledge as

encyclopedic, but times have changed. No one buys the encyclopedias or Oxford

dictionaries abandoned in the secondhand bookshops. We live in an era where we

type in the keyword, click enter, and is provided with endless information

within a second. In this Googling era, Son shows us the smart editing

technique, or in more trendy terms, the art of curating. Son’s painting is a

fusion bibimbap (mixed rice) that has

invested time in thoroughly studying the traditional recipe, kept the good

parts and gotten rid of the unnecessary. A great dish of bibimbap with nicely cooked rice with colorful and pretty toppings

that was even mixed well into harmony. Now, we have the extraordinary bibimbap. And the baton has been passed

on. Now we have the issue of how we will position this menu as a popular item

in the global village, as popular as rice noodles and burritos. Bibimbap was able to enjoy a

semi-success in New York because New Yorkers had misunderstood the dish. Crazy

about eating green, they had deemed bibimbap

as a sort of salad and opened their hearts to it. They saw it as a Korean salad

with an extra touch of rice, and regarded it as a familiar and healthy dish. It

is not difficult to witness New Yorkers with the dish, mixing the rice and

vegetables with fork and chopsticks. Then, what if we were to accentuate the

mysterious Korean or East Asian traditional Art concepts less, as they are

difficult to explain in detail, and instead promote Son’s art as a Korean

contemporary painting of a different style that resembles comic books? I merely

wish that more people and more venues would be exposed to the great fun of

reading the little details of his paintings. The truth is, there is no need to

draw any metaphor or conclusion on Son’s art. His art has always changed, is still

changing, and will keep on changing and evolving. There will emerge new

cultural references as numerous as the stars in the sky, and he will fabulously

edit the chaotic contents and allow us to look back at the present. And his

ceaseless transformations and editings will not let us down. I am impatiently

curious for his future. I cannot wait to see his works of ten years from now,

and the unknown of twenty years from now is even mystical. It is without a

doubt a great fortune that I can live his contemporary and wait for his next

works.

[i] Gu Kaizhi was a celebrated painter of ancient China. Also a talented poet and calligrapher, he wrote three books about painting theory: On Painting (畫論), Introduction of Famous Paintings of Wei and Jin Dynasties (魏晉勝流畫贊) and Painting Yuntai Mountain (畫雲台山記). He wrote: "In figure paintings the clothes and the appearances were not very important. The eyes were the spirit and the decisive factor." (excerpt from Wikipedia)

[ii] Im Kwon-taek (born May 2, 1936) is one of South Korea's most renowned film directors. In an active and prolific career, his films have won many domestic and international film festival awards as well as considerable box-office success, and helped bring international attention to the Korean film industry. (excerpt from Wikipedia)

[iii] Dooly the Little Dinosaur is a 1983 South Korean cartoon and animated film created by Soo Jung Kim. Dooly is one of the most respected and commercially successful characters of South Korean animation. Dooly became the first cartoon character to be featured on a stamp. It was printed in 1995 in South Korea. Dooly has a resident registration card, which means he is a citizen of South Korea. (excerpt from Wikipedia)

[iv] Run Hani is the first South Korean series animation that portrays the adolescent life of a girl who lost her mother at a young age and grows into an athlete. Authored by Jinjoo Lee, it was featured in a cartoon magazine from 1985 to 1987, and was produced into an animated film in 1988.

[v] As an all-time favorite subject of the gentry in Korean traditional art, the pine tree was traditionally used to portray various virtues in four typical forms of painting and under the following titles: “Sun and Moon and Five Peaks”, “Wintry Days”, “Magpie and Tiger”, and “Ten Longevity Symbols”.