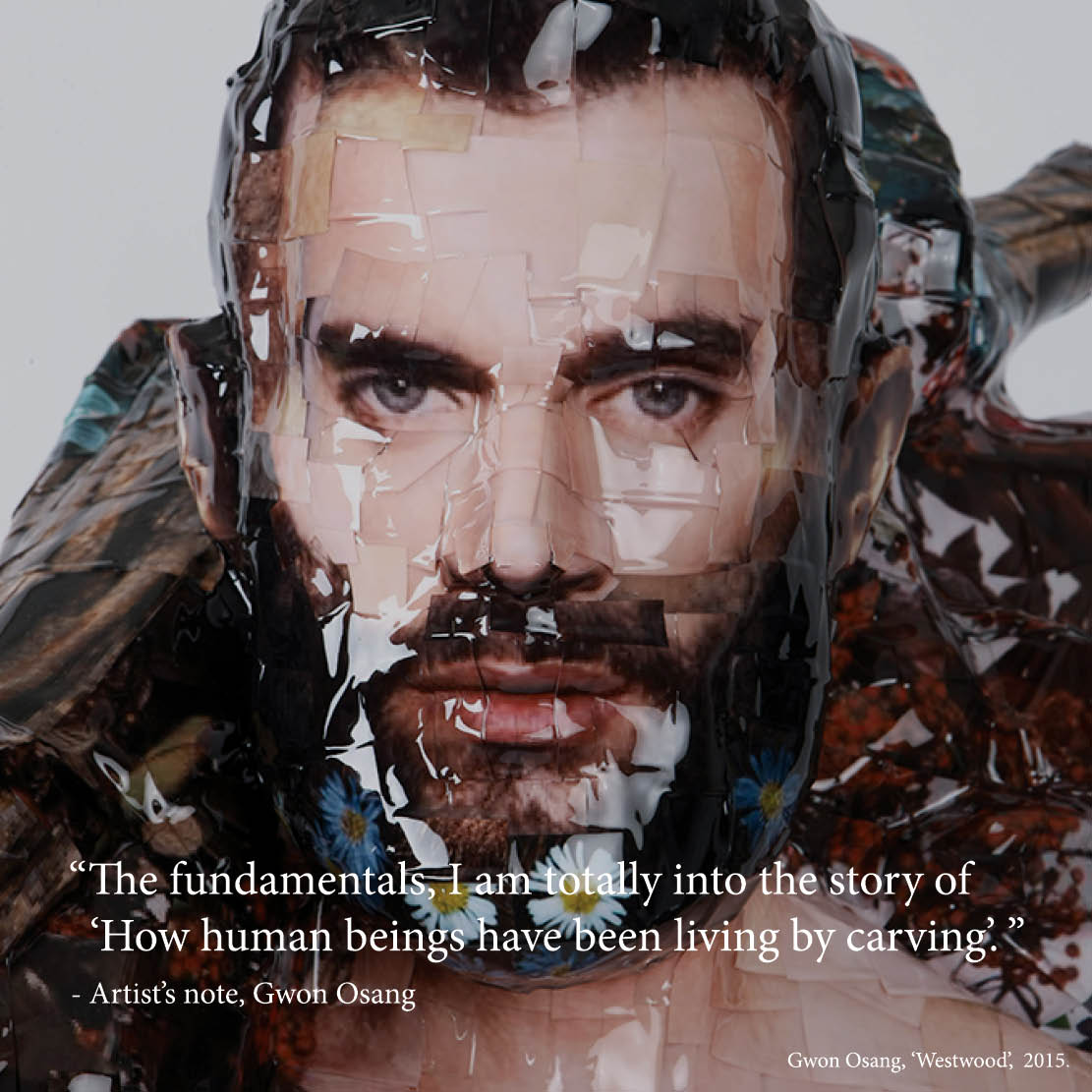

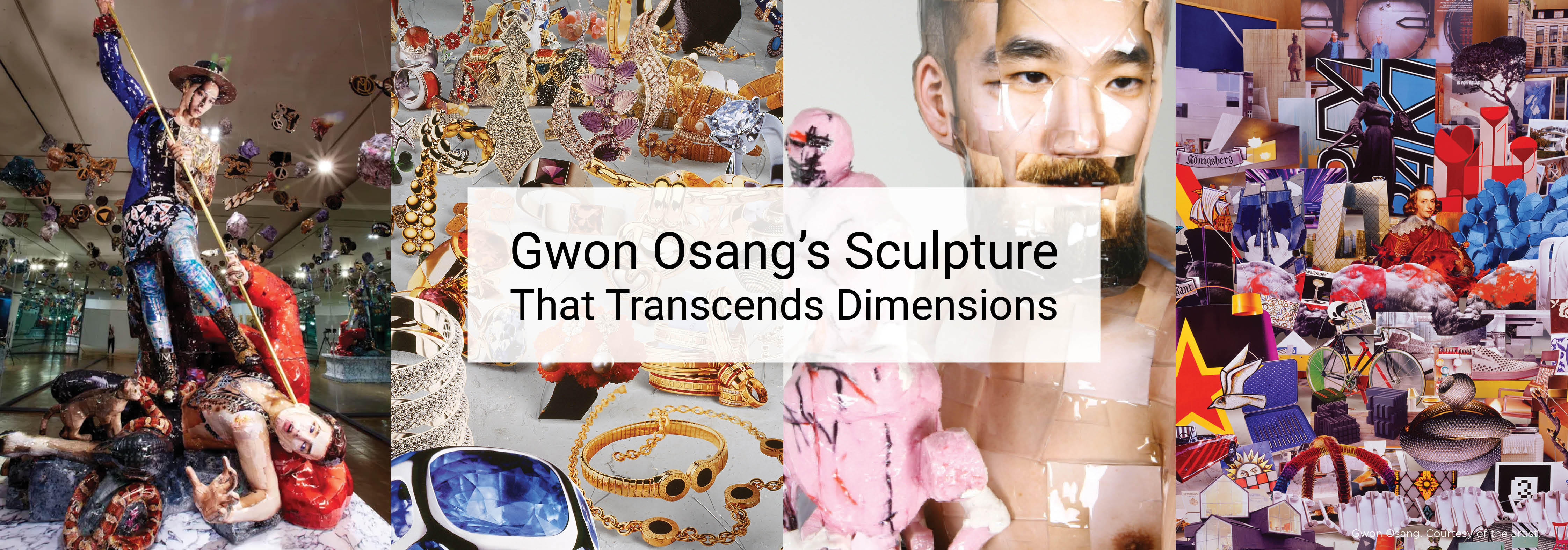

Korean artist

Osang Gwon skillfully straddles the mediums of photography and sculpture in a

rich and complex signature style that seems to nod to Pop Art, traditional

still life painting and portraiture through a most contemporary vocabulary that

finds its roots in such far-flung philosophical underpinnings as the fractured

bodies of world history, the sutured surfaces of Dadaist collage and the mise en scène fabrications of the stage. And in hypothesizing

that Gwon’s work is staged in purely theatrical terms, one may view his

multilayered constructions as hybrid images that encapsulate both leading

role and backdrop under the unified rubric of vision, for we

indeed see a narrative unfold (and fold unto itself) before in space us as our

eyes skim the pieced-together skins and veneers of his most intellectual and

aesthetic endeavors. Put simply, Osang

Gwon redefines the ways our eyes understand that which normally plays out

before them; he mimics reality through restructuring it, at times making the

two-dimensional three and the three-dimensional two, and all the while allowing

the cracks of his labor to show.

Indeed, restructuring the collective vision of a

given time and place is nothing new to the history of art. The Impressionists

re-envisioned the reality of an ever-accelerating society as laid out by the

Industrial Revolution and its churning motors that forever instilled a blurring

speed to the landscape as viewed from a chugging locomotive’s compartments. The

Dadaists forced their audiences to revel in the mundane and the absurd, to in

fact redefine both visually and theoretically what value an ascribed

work of art, often in the form of a ready-made object or pieced together

collage, would hold once presented as such.

Further, the Surrealists created landscapes of the far reaches of the

mind, environs of pure whimsy and decay that could never exist in reality, yet

that fully reflected the war-stricken nature of the moment. Decades later, the Abstract Expressionists

boiled the act of making art down to rhythmic gesture and the unconscious mind;

no longer was it necessary for art to be figurative or representative—now the

motions and emotions of paint itself were enough to hold muster, and indeed to

take over all that preceded it. Still

yet, Pop Art, Minimalism and the dozens of other artistic movements that have

arisen over the past 50 years all in their own way reordered our collective

vision. Yet again, and in a truly novel light, Osang Gwon has combined aspects

of nearly all of the above-noted “isms” of art history into a personal style

that relies on the canon, just as much as it rewrites, challenges and

undermines it in equal measure.

And although his work is not easily categorized

under the overarching headings of Photography or Sculpture, it somehow lives

between the two, simultaneously inhabiting and being the crack

which divides these powerhouse monikers of the house of art. Returning to the

theatrical base of Gwon’s work, it might best be said that, as in his much

discussed “Deodorant Type” series, he creates actors upon a stage (here the

gallery) in pieced-together photographic constructs in an attempt to develop a

slightly “off” character that is positioned well beyond the core demeanor of

his very real models that he shoots from head to toe in a deeply intimate

photographic exploration of the entire human form and all of its decorative

trappings. Both literally and figuratively, Gwon builds his characters

from scratch, picture by picture, as though a modern day Dr. Frankenstein

hell-bent on creating new life from whence there was none. The developed paper

upon which a graft of skin here or a swatch of fabric there is captured becomes

the basic building block with which Gwon endeavors to recreate life, yet

certainly not in its original form. The collage work of Claude Cahun from the

1930s certainly comes to mind, set as she was on giving birth to alternate

bodies in her work, all to subvert the status quo. And yet Osang Gwon jettisons attempts at

subversion in favor of critique; for him, the actors which he births into the

reified realm of art are everyman, the common shopper in one case, a

pensive woman in another. By serving up that which is supposed to be

commonplace, and yet scarred and clearly not natural, he urges the

viewer to realize that life and all of its social components—from the clothes

we wear, the things we buy and the way we hold ourselves—are social constructs

which are learned, dedicated to memory and re-performed on a daily basis. In

fact, the title of the series comes from Gwon’s fascination with the marketing

of Western deodorants in Asia, a place where only a small fraction of the

population has a problem with body odor. Deodorant, then, is out of place in

Asia, even though it is readily available. Extending this further, he thus

makes us question the skin we are in, both canonizing and critiquing the au

currant aspects of life—force-fed as they are—in the early 21st-century.

Fashion certainly plays a primary role in Gwon’s

production, but his work is not simply an attempt to provide a glimpse of urban

street style. Politics, too, I would venture, is at play here. Thanks to the

ever-present fissures and seams that mark the points of contact between the

hundreds of photographs that compose his figures’ corporeal forms, an

ever-present sense of violence and trauma is embedded in the glossy veneers of

Gwon’s actors. And certainly the notions of war, terrorism and global security

are nothing new to us, embroiled as our current world is in conflict and

military maneuvers. Whether it be the reality of broken bodies on the field of

combat, or those in the midst of our urban centers when a terrorist’s bomb

maims, imagery of broken bodies has become standard issue in mainstream

news outlets, and unfortunately on a near daily basis. By literally presenting scarred forms that

seem to have been pieced back together again a la Humpty Dumpty or Shelley’s

famed monster, Osang Gwon both acknowledges the lived tragedies of our times

and provides hope that things might one day get better and come back to some

(albeit imperfect) sense of normalcy.

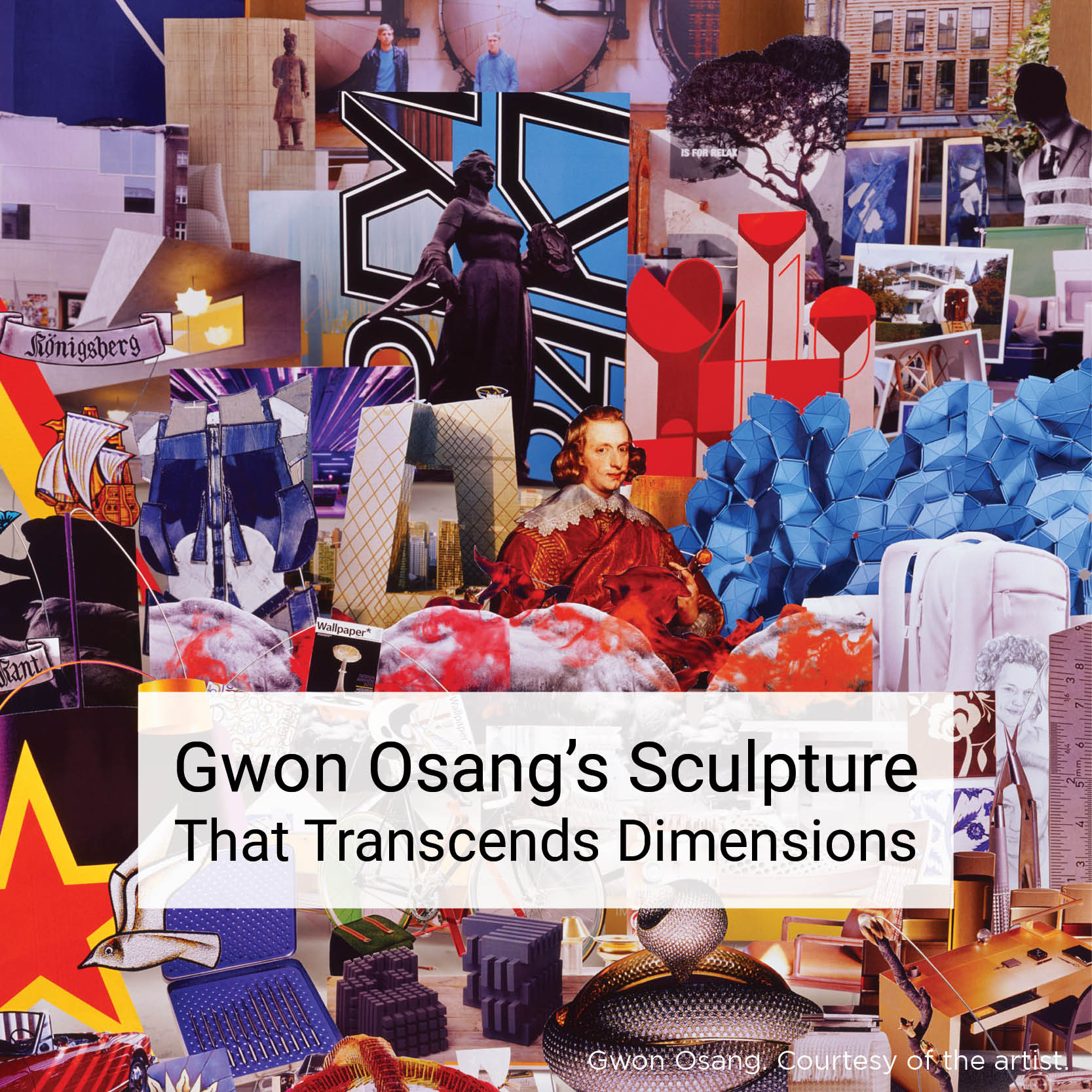

Gwon’s critical stance on vision and materiality

also plays out in his series “The Flat.” With imagery culled from the

editorials and advertisements of high-end fashion magazines, Gwon creates an

apparently flat wall of luxury repeatedly throughout the series. Whether

it be fabulously expensive watches, luxury perfumes and creams, or jewels and

baubles of exorbitant cost, works in “The Flat” become fields of

consumerism writ large as the entire picture plane becomes completely populated

with the markers of excess and brand-name logos. This is of course nothing new

in an age where contemporary artists like Japanese wunderkind Takashi Murakami

and American art star Richard Prince help the venerable French luxury retailer

Louis Vuitton sell its high-priced purses with their much-sought-after

designs. Yet, Osang Gwon is not

interested in creating new motifs for commercial applications; it is the

products themselves that he takes up to address the sheer saturation of

life today with brand logos and must-have accessories. And although his

photographs appear to be collaged assemblages of all-out consumption, they are

actually sculptures first and foremost.

For, in fact, Gwon creates stand-up cut-outs of each item—blown up to

super-size—and arranges them in a large space in his studio, stretching out and

back several feet in all directions. By placing the camera directly in front of

and on the same level as his constructed sea of conspicuous consumption, Gwon

achieves a flat picture where all products appear to be on the same plane, when

in fact they originally occupied a variety of positions and sizes in real

space. Again, Gwon subverts our known reference points to visually accessing

imagery, forcing us to question that before our eyes. As a critique of the upper echelons of the

retail world, “The Flat” series might inspire us to think twice about spending

too much on the latest fad, or in some cases might compel us to dive right in

and buy, such is the sheer beauty of the glowing bounty contained within. Yet,

and more importantly, the series makes us question the concept of materiality

itself; both in terms of the materials from which a work of art are made

as well as the materialism of life in the world today. Osang Gwon serves

up this series in the language of advertisements and display; the way we

choose to read it is purely individual and based primarily on our own

predilections—and spending habits.

As discussed earlier, Gwon’s work somehow

presents objects as both primary actors and prime components of the sets

upon which they play. Especially with “The Flat” series, individual items may

populate the picture-sculpture, but taken together, they become pure wallpaper,

a stage set of all-out glitz. In much the same vein, characters in the

“Deodorant Type” series may appear to be stand-alone identities, but thanks to

the very nature of their piecemeal construction they ultimately appear

arranged, as though they are carefully thought-out backdrops against which

living and breathing bodies (i.e. the viewer) might play out their own actions.

It seems then that Gwon is very aware of the interactions that his

viewers will inevitably have with his work, whether fantasizing about being

broken down component by component and then being rebuilt, or being set adrift

on a window-shopping spree that can only result in the purchase of art, not the

cardboard shells of haute culture/couture from which they are made.

And in the end, we must realize, especially in

today’s markets where art prices continue their upward climb, that in almost

all aspects of life, our vision, and by extension, our judgment, often has

strings (with price tags) attached. Osang Gwon is fully aware of this

unavoidable component of the contemporary art world, and in his quest for

describing and redefining the materiality of art, he inevitably reformulates

the ways in which we see it. Indeed, in his series “The Sculpture,” he

once again undermines our gaze by presenting us with luxury cars and their

motors served up in candy-coated Technicolor, when in fact these very

plastic-looking models are actually made from bronze which is then painted over

with bursting hues. For example, The Sculpture 5 (2005) is a life-size

bright orange Lamborghini that seems to still be wet thanks to its

glistening—and lumpy, as in freshly modeled—surface. Only when the

viewer reads the label or sneaks a touch does she realize that the car is in

fact made from the most traditional of high art sculptural materials, bronze. Here

too, Osong Gwon throws us a conceptual curve ball, tricking our eyes to believe

one thing, when, in actuality, something quite the opposite is true.

Thus thinking about Gwon’s work and all of its

exquisite complexity, only a small portion of which I discussed above, it might

be best to catalogue his work under the more apt concept of the manifold

in lieu of such terminology as Photography or Sculpture. For in physics, the

manifold is best described as that which allows complicated structures to be

understood through simpler more common-place spaces. And that is exactly

what Osang Gwon is attempting to do in his work, folding, manipulating and

displaying a litany of complicated concepts as far-ranging as history,

economics, materiality and human nature in a universal container that both

mimics, and yet always and forever subverts, that which we think, or thought,

we knew as truth. And in so doing, like the innovators who came before him,

Osang Gwon gives us a new way of seeing, and indeed of knowing, the world

around us.

Eric C. Shiner is an independent curator and art historian specializing in Asian contemporary art. His scholarly focus is on the concept of bodily transformation in postwar Japanese photography, painting and performance art. Shiner was an assistant curator of the Yokohama Triennale 2001, Japan's first ever large-scale exhibition of international contemporary art, the curator of Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York at Japan Society in 2007 and the co-curator of the exhibition Simulasian at the inaugural Asian Contemporary Art Fair, New York in November 2007. He is an active writer and translator, a contributing editor for Art AsiaPacific magazine, and an adjunct professor of Asian art history at Cooper Union, Pace University and Stony Brook University.