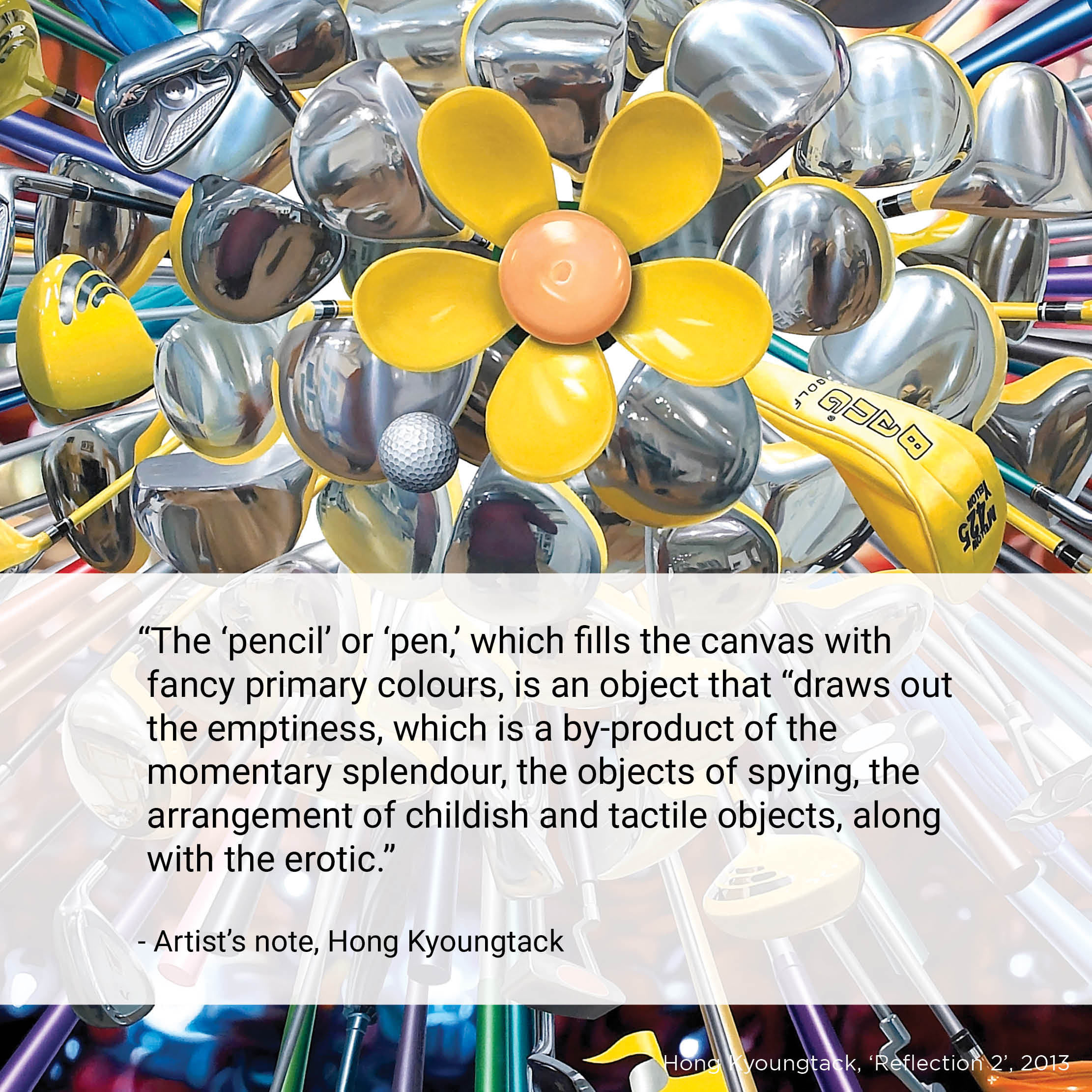

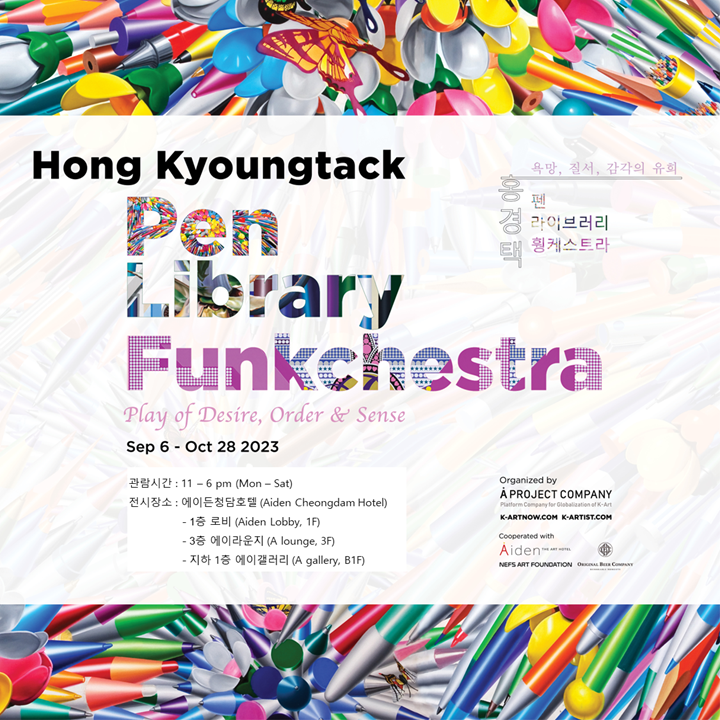

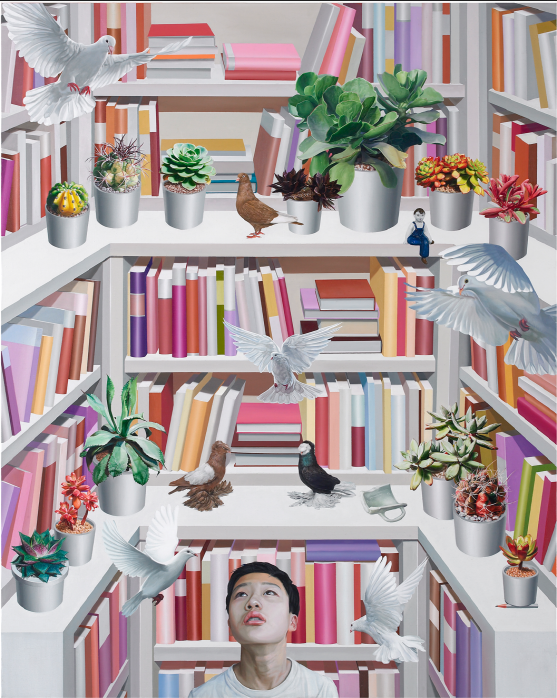

Inspired by the contemporary elements found in Chaekgeori, a genre of Joseon Dynasty still-life paintings with books as the main subject, artist Hong Kyungtack (b.1968) embarked on the series Library. Depicting spaces filled with bookshelves and books, the Library series captures various spatial elements.

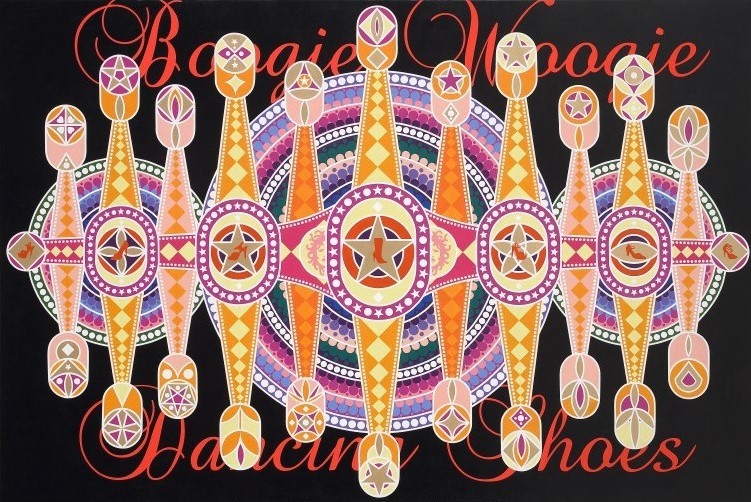

Exhibition view of Yooyun Yang's solo exhibition at the Amado Art Space/Lab, Seoul. (September 6 -September 29, 2019). Courtesy of the Amado Art Space/Lab.

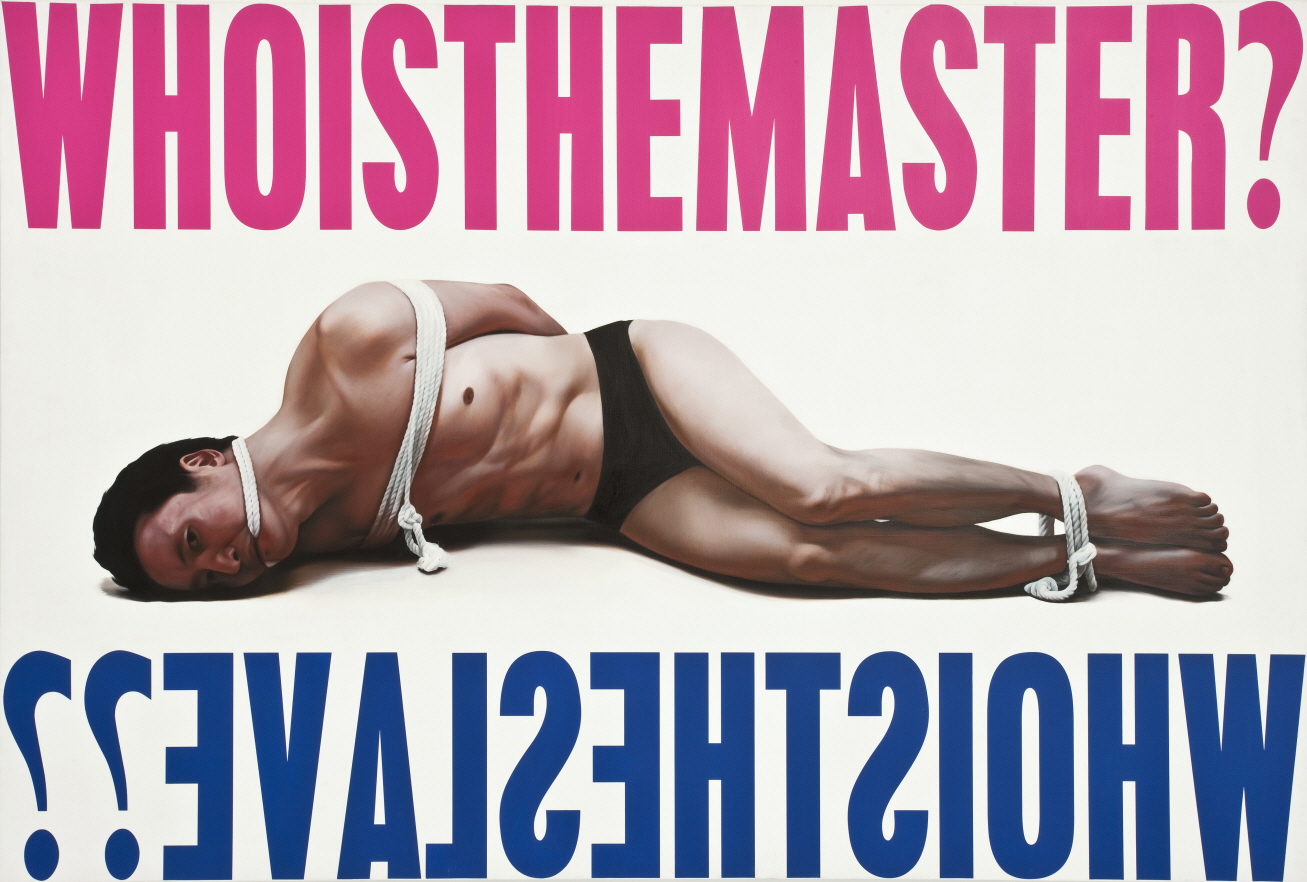

In the late 1980s to early 1990s, the Korean art scene was mainly divided into Dansaekhwa, Korean paintings that are abstract and minimalistic with a focus on texture and materiality, and Minjung Art, a South Korean socio-political art movement. Most of the art professors at Korean universities taught abstract art, while the streets were filled with mural paintings, banners, and pamphlets created by young artists agitating for political change.

Artists who did not want to be part of that art scene sought to find new artistic trends by studying abroad or pioneering their own paths.

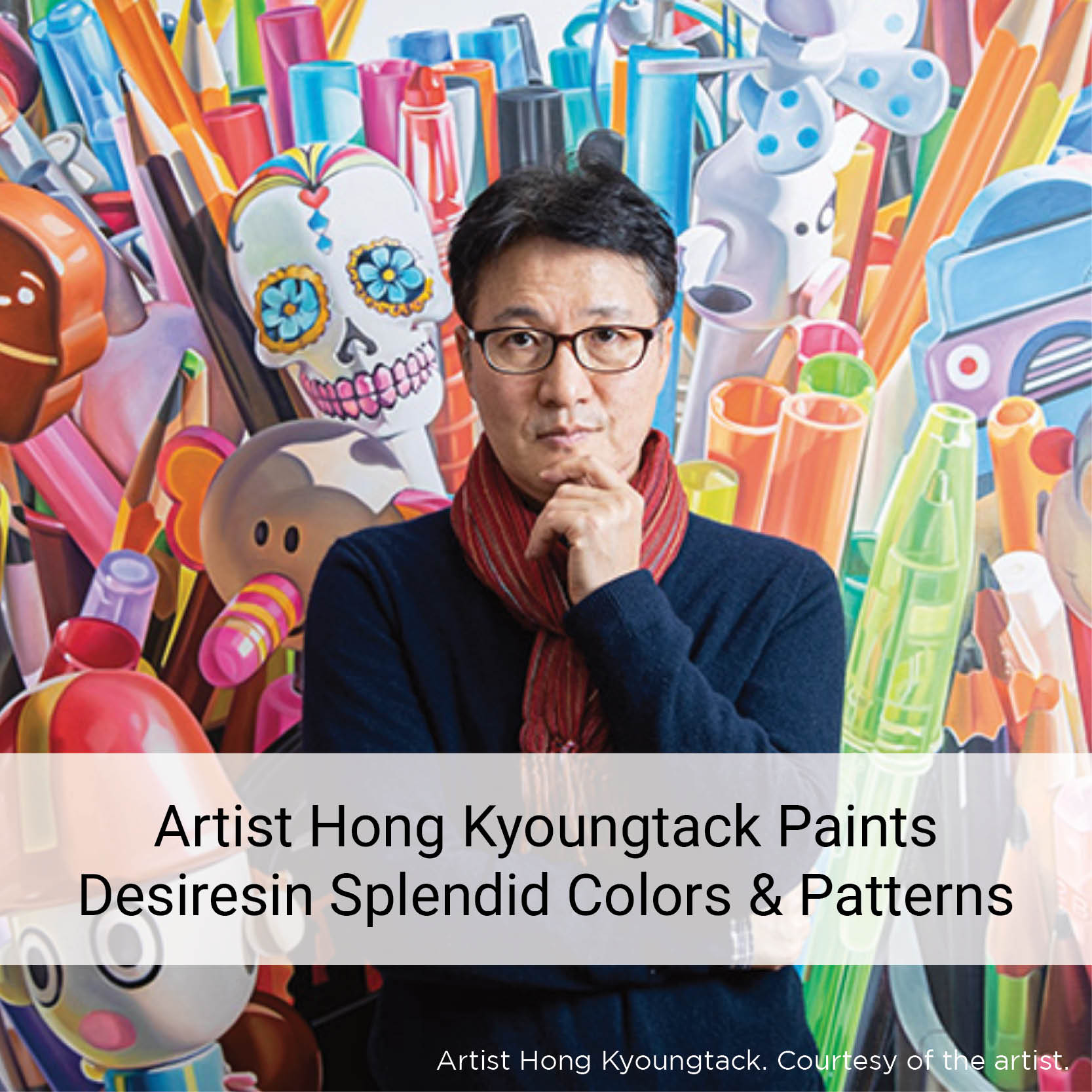

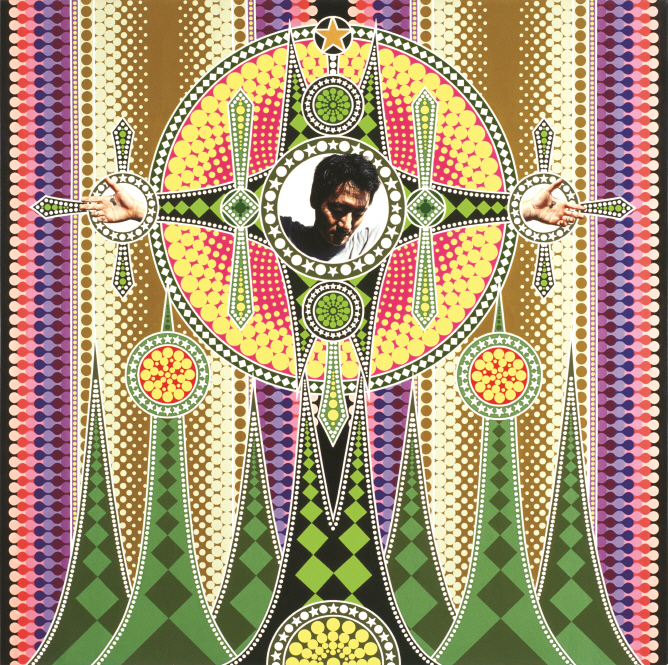

One of the artists who sought to build their own unique artistic world during that time was Hong Kyungtack. Hong gained significant attention in 2007 when his work Pencil I was auctioned at the highest price at Christie’s Hong Kong. Since then, many Korean media outlets have introduced Hong as an artist who achieved the highest bid for his artwork. However, it is important not to overlook his broader artistic world, which encompasses diverse stories.

Hong, in seeking a different path from the abstract Danaekhwa and Minjung Art movements, began to focus on drawing still-life paintings in his third year of college. His interest in depicting objects, however, had been present even before that.

During a time when personal internet access was scarce in Korea, art students relied on street vendors who laid out various books for sale to access new information. It was during his first year of college when Hong coincidentally came across a book titled “Minhwa of the Joseon Dynasty (이조의 민화, 李朝の民畵)” at one of these vendors. He became fascinated by the still-life paintings from the Joseon period of Korea, which featured books known as “chaekgado” or “chaekgeori” in Korean.

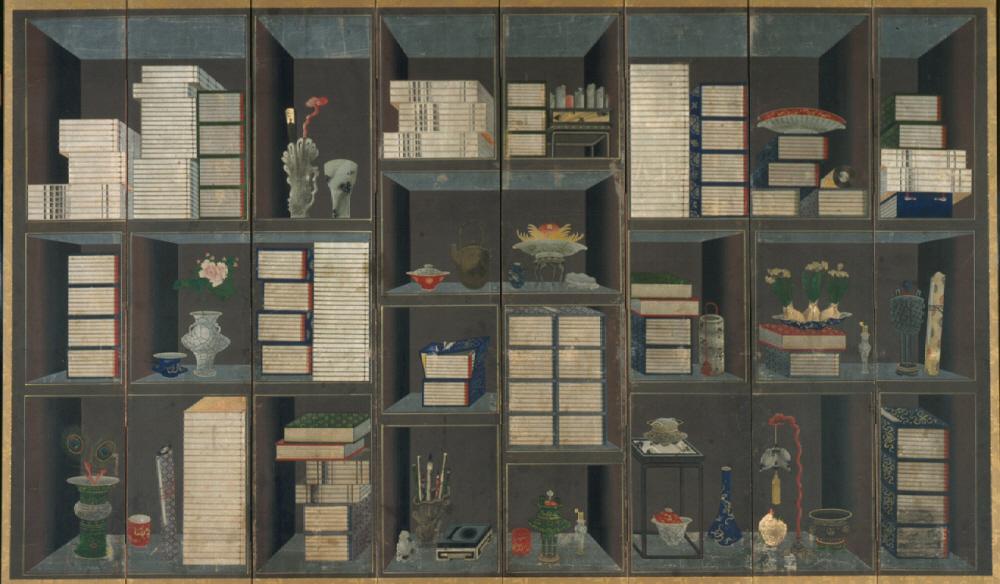

Yi Eungrok, 'Scholar's books and things,' Created: between circa 1860 and circa 1874. Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum San Franscisco .

For Hong, the paintings from the Joseon Dynasty were incredibly modern. This was because the objects that composed those spaces and the overall composition of the paintings were unique. The paintings employed reverse perspectives, where objects closer to the viewer were depicted narrower and those farther away wider; they also incorporated multiple perspectives within a single frame, creating a multi-perspective effect that resulted in a sense of depth.

“Chaekgeori” paintings originated from a Chinese decorative cabinet called “dabogakgyeong (多寶格景),” which depicted various valuable items displayed in a cabinet. The dabogakgyeong was influenced by the “Cabinet of Curiosities” in the Western Renaissance era, which employed small collections of extraordinary objects

Consequently, the chaekgeori paintings adopted Western artistic techniques, such as chiaroscuro, and incorporated elements of linear perspective. Influenced by these factors, chaekgeori paintings gained popularity during the Joseon Dynasty, particularly during the reign of King Jeongjo. This art form continued to be popular throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, becoming a prevalent style among the general public.

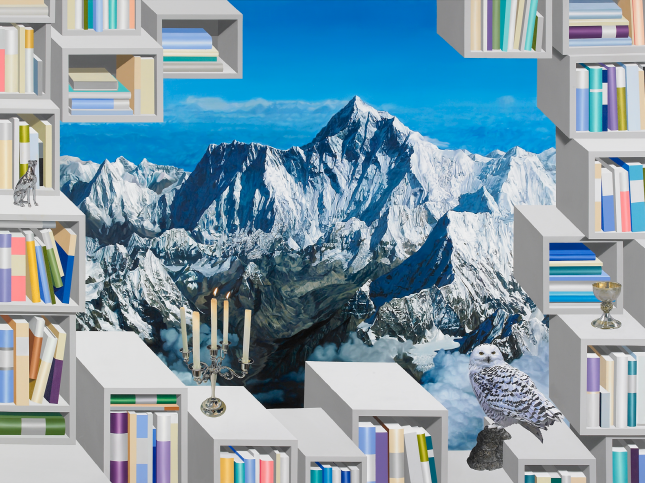

Inspired by the coexistence of Eastern and Western cultures found in the chaekgeori paintings, Hong consistently developed his artistic world with his own perspective through the series called Library. In this series, Hong depicts various objects alongside bookshelves and books. But the series, in particular, highlights the spatial and temporal elements expressed through the bookshelves.

Hong Kyoungtack (홍경택), ‘Library-Mt. Everest (서재 - 에베레스트산),’ 2014, Acrylic and oil on linen, 194x259 cm.

The most distinctive feature in the Library series is the portrayal of confined spaces. The bookshelves are filled to the brim with books, creating a sense of being tightly packed within the room. In some artworks, the books appear as if they are about to spill out, and at times glimpses of landscapes from inside the study room can be seen, yet even those scenes seem to be filled to capacity.

The depicted study appears as a physically confined space, but its inherent conceptual world expands infinitely. In the series, the rational space of a study room becomes a stage for irrational and fantastical situations. For instance, the depicted study room can sometimes resemble a mysterious cave. Just as ancient ancestors believed that painting hunting scenes on cave walls connected them to the actual events of hunting, or as we believe we can glimpse a new world within the enclosed space of a movie theater, a fantasy world unfolds in the confined spaces of Hong’s work.

Furthermore, books embody human knowledge, culture, and history, containing a wealth of information. Books written in the past can be passed down to future generations. Therefore, books represent a medium that connects the past and the future, the close and the far, transcending space and time.

Also, each book’s unique shape and size implies a different worldview. Among the works that reveal this worldview are those that Hong has recently begun to attempt.

Inspired by his Library series, Hong has started to paint images of a single book. Animals or objects poke out from the books as if the texts are trying to contain them. Just as every living being carries its own life narrative, each book contains a vast narrative of its own. However, just as we have limitations in fully understanding the worlds of others during our own lives, the books in this series imply self-contained infinities while also revealing the limitations and oppressions inherent in an individual’s life.

Hong Kyoungtack (홍경택), ‘Library – Paradise(서재 - 낙원), 2016, Oil on linen, 162x130 cm.

When observing Hong’s artwork as it appears, one may think of it as a representational painting. However, the form of the books, composed of straight lines and squares, as well as the convergence of colors on each surface, give the impression of a color-field painting with abstract elements incorporated.

Beyond their symbolism, Hong is also attracted to the universal shape of the book: the rectangle. The artist believes that the rectangle is a perfect shape, the best one to represent humans and the world. The circle is widely considered the perfect shape, but it evokes a sense of instability or uncertainty. The circle also symbolizes the sky and God, while the square symbolizes humans and the earth, as humans have long believed that the earth is flat and square. The square is also a stable shape made up of vertical and horizontal lines, with the vertical representing God and the horizontal representing all the world.

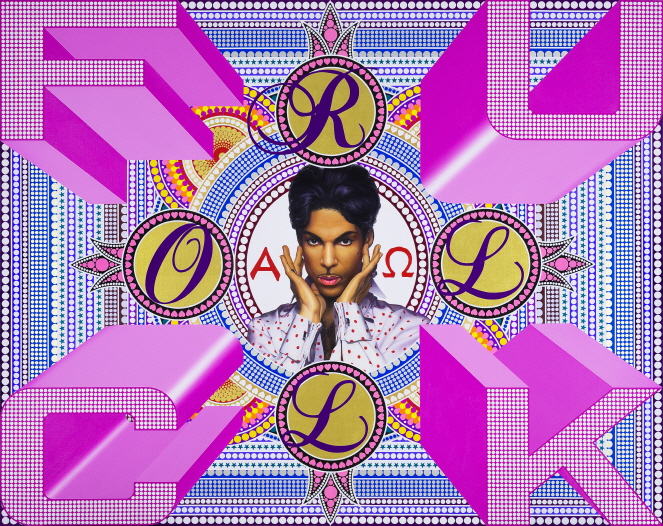

Hong’s paintings, including those in his Library series, incorporate various elements that constitute the artist’s inner world. Examples include references to popular culture and the classics, life and death, and Eastern and Western culture.

Viewed through this lens, Hong’s Library series becomes a singular space that simultaneously encompasses heterogeneous yet interrelated subjects. From the East and the West to the sky and the earth, from the infinite and the temporary to the open and the closed, figurative and abstract, Hong encompasses all these elements within a single canvas.