“When

I showed you my work before, you said you wanted to write something. I know the

schedule’s a bit tight, but I wanted to talk to you about it.”

“Me?”

Hmm. I couldn’t really remember.

“Yes.”

His response was assertive.

He

must have been showing me artwork for an exhibition, and that’s what I had told

him.

It

seemed a lot different from his earlier work, but it somehow felt similar in

its context.

I

was drawn to the recklessness of something that must have been impossible from

the outset? something different the sort of photography that captures facts and

places, something that attempted to capture time and the universe alongside

history.

And

yet…the pictures were pretty, but they were also sad, painful.

He

titled the first of his star photographs Rifling. Referring to the helical

groove in a gun barrel, rifling is said to cause the bullet to gain rotational

inertia and a stable trajectory as it rotates along the spiral. Interestingly,

Kim Taedong viewed the trajectory of movement in the photograph of stars as the

spiral of a bullet? as rifling. This leap from stars to bullets seemed like

something of a stretch, but as I heard him describe it, I sensed how the stars’

path might appear similar to rifling.

It

also occurred to me that what led him to so naturally make the leap from a

star’s pattern to bullets may have been the story behind where the photograph

was taken. rifling-011, which could be called the first work in the Rifling

series, had apparently been taken in a wartime historic site on the grounds of

the Cheorwon Waterworks. The facts surrounding this area, which often appears

in discussions of the DMZ around Cheorwon, are still in dispute. Built in 1936,

the Cheorwon Waterworks were Gangwon Province’s first water facility. Some

claim the location was also used to detain Japanese collaborators during the

Korean War; others allege that over 300 people were shot or buried alive in

storage tanks amid the flight from the area during the northern advance. It is

difficult to confirm what the truth is, but it isn’t hard to imagine that the

events that took place here were by no means aromantic or happy tale.

I

imagined him coming here in the darkness after the sunset, with no one else

around, and setting his camera on a tripod to capture the stars. At any moment,

a wild animal could come springing out. A situation where nothing that happened

would seem strange, nothing could be predicted. All sorts of thought would have

come to mind as he stood out there in the middle of the night. He would have

waited there, alone, and looked up at the sky to find it filled with stars. The

atmosphere would have been damp and chilly. Seen amid that fear and terror, the

stars would have appeared so beautiful? and in the moment of admiration for

that beauty, there would have been no thoughts of anxiety or tension.

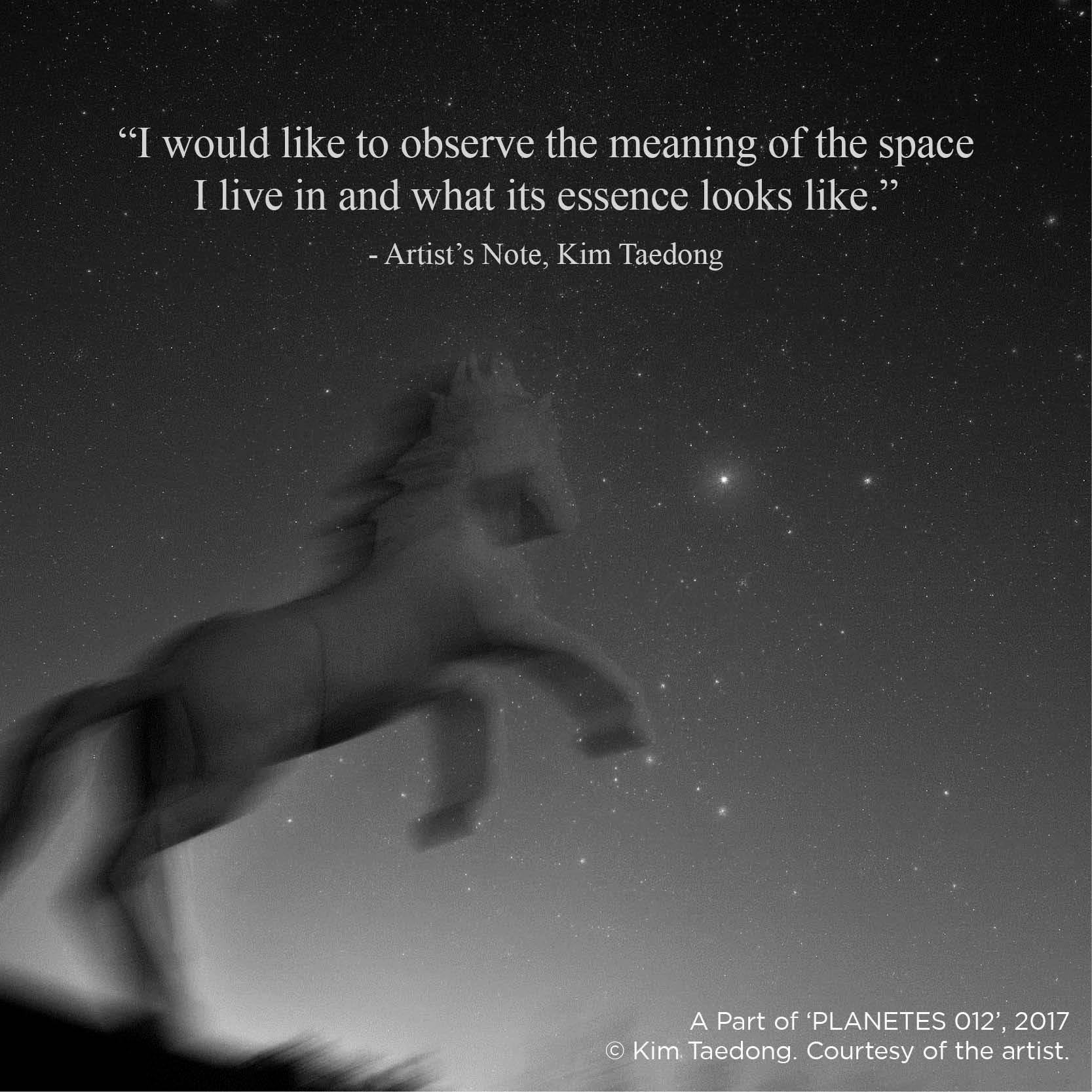

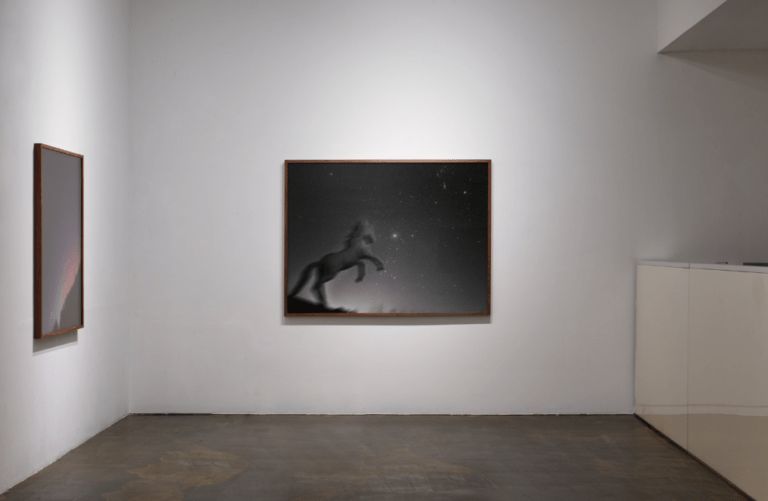

With

its shining stars, the photograph was quite beautiful, gently capturing the

gaze, yet I kept feeling my heart lurch in my chest? a fact that did not seem

due to the “rifling” title alone. There were the glimpses of war memorials and

other monuments in the image, the settings that those traces called to mind,

the scars of war, the division of a nation. Had it not been Cheorwon, had it

not been the vicinity of the DMZ, had it not been a place marked by the scars

of wartime carnage and division, the stars would have told a different story.

This explains the gunshots and shouts that can be heard in the photograph’s

stars. The picture itself is quite tranquil and gentle, yet the viewer feels

stunned and uncomfortable. If one were to suggest that this stunned discomfort

was a mistake on my part, the result of overidentifying with the story conveyed

by the setting, I would have nothing to say to them. So itis with Kim Taedong’s

stars.

He

described the process of photographing the stars as having been difficult. The

hardest part, he said, was following the stars and fixing them in place. Kim’s

star photographs are not pictures that capture stars alongside some object that

appears in the image with them. Producing with something called an “equatorial

telescope,” they use long exposure times to track and fix stars in order to

capture them in the image. The aperture is kept open for the better part of an

hour, and the process of moving precisely with the stars is quite a bit

different from the typical “snapping” of photos. Not only that, but the artist

also said it was difficult to predict how the image would come out during the

tracking process. It might seem like a fool hardy approach indeed in an era

where we can push the shutter and instantly see the results. When he is lugging

over 100 kilograms of equipment to his setting, there is no actual guarantee he

will be able to work at all. Many times, he must have waited and waited until

daybreak, watching the weather and surrounding conditions change from one

moment to the next, until eventually having to return without a single shot.

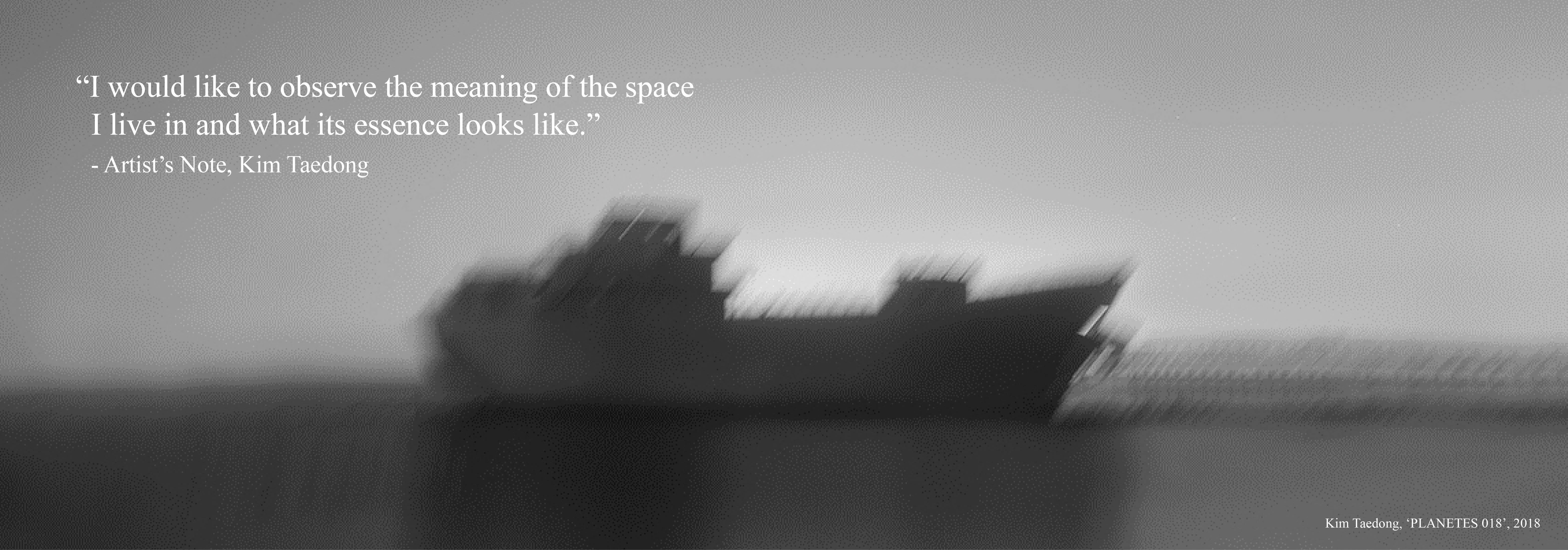

So

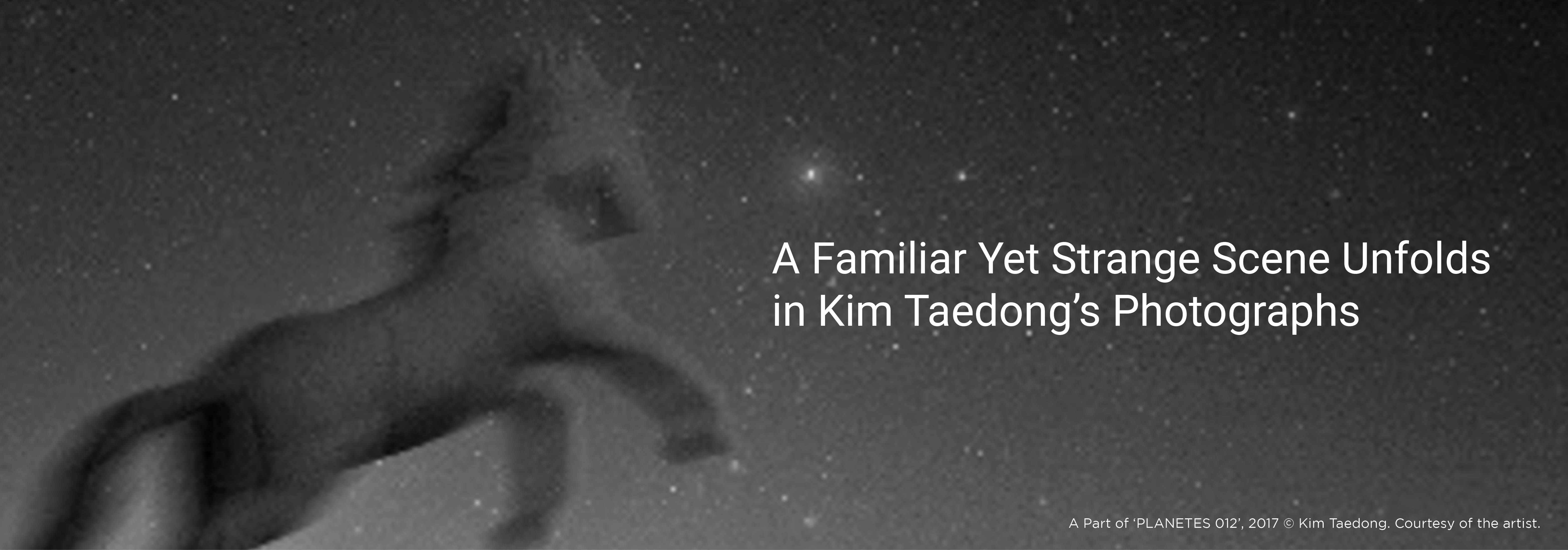

the stars that appear in Kim’s star photographs are not the stars at the

“moment” the shutter was pressed. They are images of starlight, which has

traveled over hundreds of millions of light-years to arrive now on Earth. The

resulting images of stars, presented to us clear and unwavering by opening the

aperture and following their traces, are thus records of time? a time beyond

the scope of human experience. It is the image of the wavering object

underneath that starlight, at this moment. The wavering present under the stars

is all the more realistic for being unclear. Like a composite, a painting, the

wavering image conveys a subtle sense of tension, as the seemingly realistic

objects suddenly lose their temporality, seeming instead like a stage set.

Kim

Taedong’s star photographs have been come mainly as part of two series:

Rifling, which may be seen as the beginning of his work with stars, and

Planetes. They differ in the relatively stronger or weaker emphasison war or

historical imagery, but they share a common grain in being records of “star

time.” The most interesting thing about the works in these two series may be the

unseen, dynamic movement that arises in the viewer beholding the photographs.

This is one of the elements setting Kim’s star work apart from other

photographs: even though it is a two-dimensional photographic image, it creates

a temporal and spatial flow in which the gaze of the viewer looking upon it

becomes either expanded infinitely beyond the image or compressed in front of

it. Just as things seem to be blurring as we focus on the stars, some objective

information enters our gaze? evidence of history, such as the Korean War and

its associated monuments. Our attempts to focus sentimentally on the romantic

motif of the “star” are frustrated by the marks of information captured within

the gaze. Just as our gaze is ready to expand out into the vast reaches of the

universe, a wavering image of the object drags it into the present. At first

glance, the image seems quiet and peaceful, but the movement of the gaze within

that image is more dynamic than in any other picture, a warlike back-and-forth

between reason and feeling. He seems simply to have photographed stars, yet the

images allow for an odd experience where we are struck by some kind of vague,

weighty emotion that cannot be put precisely into words. These are the star

photographs of Kim Taedong.

When

I first heard from Kim about his Rifling series of starimages, it seemed a bit

random to me? why stars all of a sudden? Looking at this earlier Day Break

series, showing the unfamiliar people encountered late at night or early in the

morning while the city is sleeping, or Break Days, depicting the sub-center of

Seoul where he has long been living, I had imagined that he would continue on

like other young photographers, showing stories of daily life and in the city

within a similar context. Yet when I think back on it now, the potential for

his star work may have been there from the time of Day Break. Night in the city

wears a different face from the day. City night scan be brighter than the day,

looser and sometimes sadder. It is a time when the barriers we just manage to

sustain can loosen up. While he was working, the artist would make his way

through the city night like a hunter or fleneur; to him, night was familiarity.

Never mind the dazzling lights? the stars were there, in the night sky.

It

may have been this familiarity with the night that allowed him to venture out

to the waterworks with his camera in the middle of the night for the Real DMZ

project. But the night that he encountered in Cheorwon? night in a place where

the traces of history are still very much present ? may have had a different

face to it. He may also have been entranced by the stars that were not visible

in the city. In any case, I had the sense it may have been a natural process

for him to open up his camera’s aperture to the stars.

Planetes

is the title chosen for this exhibition, which includes works from the Rifling

series (the star of Kim’s work with star) and the subsequent Planetes series.

The name “Planetes” was taken from the title of a Japanese anime work telling

the story of Hoshino Hachirota and his crew, who clean up debris around the

Earth caused by rampant space development. Taken from the Greek, planetes is

said to mean something like “wanderer” or “traveler.” Did Kim see something of

the planetes in himself as he set out at night with his equipment to photograph

stars? Did he see the planetes in his own inability to come out with any

definite answers amid the reality of Korean history and society that he

confronted as he photographed those stars? Perhaps he saw himself in the image

of Hoshino wandering amid ideals and reality, cleaning up space debris as he

goes.

Kim

Taedong’s travels and wandering are still going on. While Planetes was begun as

a work connected with the Korean War commissioned by the Australian War

Memorial, it also seems to have served as turning point allowing his work with

stars to move beyond its “war” and “history” framework and get at a more

fundamental approach. Looking at the photographs in the Planetes series, one

senses how the connection with the “star” and “war” motifs is somewhat looser.

PLANETES Project, AU 005, a night image of Canberra taken when the artist

happened to encounter a sea of clouds while working there, sticks with me as

something akin to both an ending to this exhibition and a beginning for the

next. Showing the lights of the city wavering against a blue-tinged night sky

filled with stars and a sea of clouds stretching out underneath, the photograph

seems to suggest what awaits him now: a time not for seeing through the stars,

but seeing the stars as they are.

Having

returned to the city, he will continue to work there.

But

perhaps his perspective on the city has changed.

There

are stars in the city too.

And

when you look, there were stars every place he had been.