- Your solo exhibition "Painting

Lost " started with the same name, which you presented in 2021. I was

impressed by the empty glass tube with silkscreened letters printed on the

inside. Can you tell us about this exhibition?

I have been collecting

materials and stories about paintings for a while. One day, I was reading a

biography of Sinsaimdang, and there was a section about Sinsaimdang's sanshou

paintings. Currently, there are no sanshou paintings left, so the images can only

be inferred from the text. Since then, I began to collect records of the lost

paintings. For example, the Silla painter Solger (率居)

mentioned a pine tree painted on the wall of Hwangnyongsa Temple by the painter

Lee Ye-sung (李如星), or a letter from Heo Gyun (許筠) to his friend Lee Jung (李楨) requesting a

painting. After selecting about 20 of the collected stories, the artist turned

them into a series of works, including "No Picture" (2021). This work

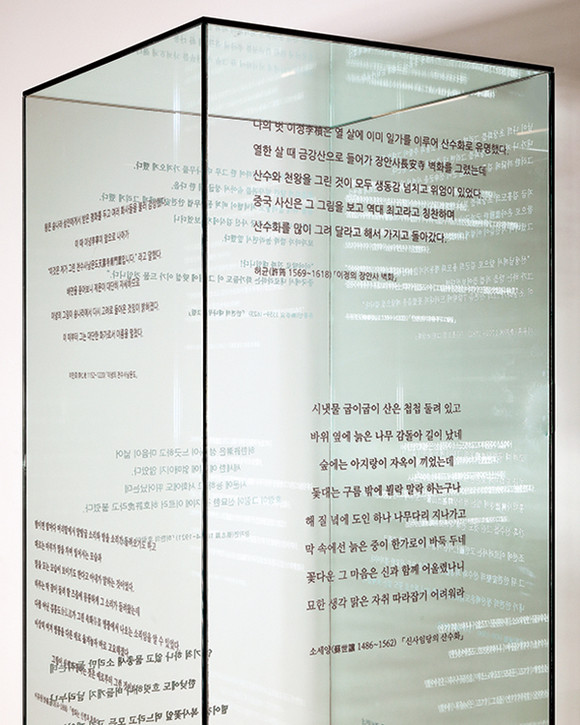

was exhibited at the 21st SongEun Art Grand Prize Exhibition. Inspired by the

glass storage boxes used to preserve artworks in museums, I made a glass box

that reflects the height of the folding screen and placed nothing inside.

Instead, I silkscreened excerpts from some of the "paintings without

pictures" texts I had collected onto the glass surface, and I removed the

insides of the old folding screens I had been collecting, colorfully decorated

the outside, and folded them together next to the glass box for installation.

The empty glass box, the texts on the paintings, and the folding screens that

cannot be seen, reflect the themes that have always interested me, such as lost

or sparse traditions, the problem of the gaze, the way museums exhibit, and

East Asian art history. I wanted to create a paradoxical space that reveals

itself through absence, and since it was not enough to end with one work, I

later conceived an exhibition of the same name. For this solo exhibition, I

made a different folding screen from the previous one, centering on the glass

work I made in 2021, and also made a collage of reproductions of sanshou

paintings that were removed from the folding screen. I wanted the meaning of

'paintings without' to become clearer, such as the prohibition or frustration

that barbed wire evokes, and traditional paintings that are not authentic.

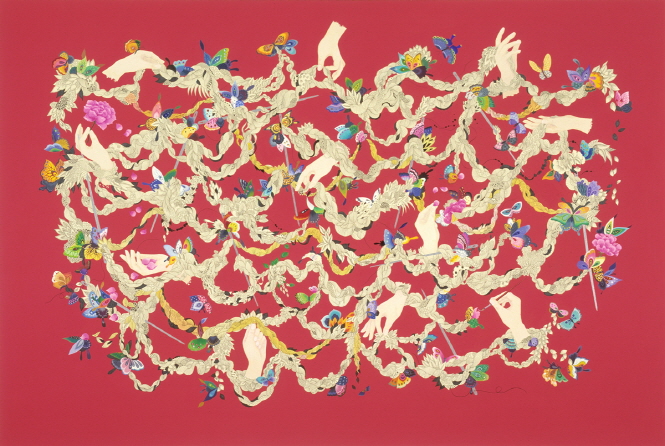

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

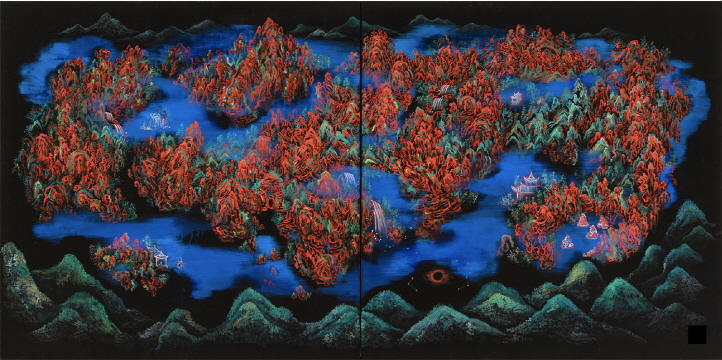

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- One might expect to

visualize works that remain only on paper.

It was fun to imagine the

pictures while collecting the words. I wanted to actually draw the picture in

my head, so I tried in various ways, but I felt like I was slipping and sliding

without completing it. In the end, I came to the conclusion that there is no

such thing as "nothing that existed," and that I had to leave room

for the loss I felt and for my imagination. We in the 21st century can't draw

like the people of old. It is not because we lack the skills or have learned

less, but because the tradition has not been passed down in its entirety, and

we have moved away from a time when drawing and writing existed in harmony. I

organized the first and second floors of the gallery differently, hoping that

the viewer would fill in the gaps with their imagination by recalling things

that do not already exist, while the second floor exhibited the results of

drawing, writing, and creating freely in a state of 'nothing'.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- When I first saw the title

"Paintings Lost," I thought of the idea of space or emptiness. Of

course, it connects to these concepts, but what struck me was that it started

with a very specific story and experience. "A few years ago, as a way of

questioning whether this is the right time, I drew a tattered and broken

bunbangsau and calculated the discrepancy between the past and present of art.

(interruption) However, when viewed together with the 'missing paintings', the

Bunbang Sau takes on a different meaning," you write, and I would like to

hear more about this.

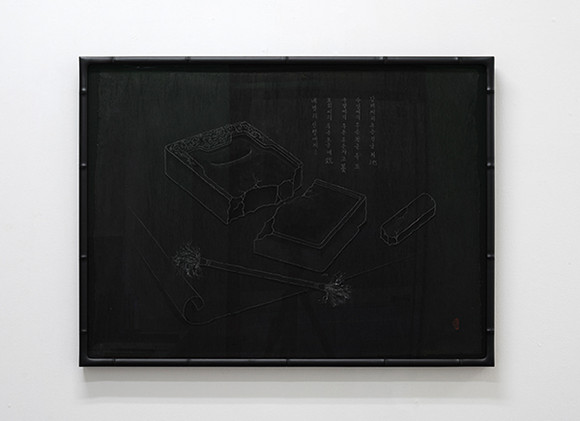

Some of the works in the

exhibition have empty and empty characters. I too have thought about the

meaning of nothingness in different ways. In my solo exhibition 'Friends from

Far Away' at the Security Inn in 2020, I hung a work called 'Moon Bang Sau' (2020)

on one side of the exhibition space. I painted old wrinkled paper black and

drew torn paper, disheveled brushes, cracked ink, and broken inkstones on it

with graphite. One of the Joseon Dynasty's folk tales, "Night Play in the

Study," contains a conversation between the spirits of Munbangsau at

night. One of them laments that their time has passed and longs for the past. I

found it interesting that even 500 years ago, the spirits were saying that they

were outdated. There was a parallel in that there are still attitudes that

consider oriental painting as old and not modern. The story ends with a man who

hears Bun Bang Sau's lament and performs a sacrifice for the four spirits. I

wrote the words of the ritual on one side of the painting to make it look like

a shoemaker's poem. Through this painting, I wanted to ask the question,

"Can we say that our time is complete when we treat any history or

tradition as if it doesn't exist?" This year, I redid "Moon Bang

Sau," which retains the reflective attitude, but adds a sense of

joyfulness to the work, even with broken ink and anvils.

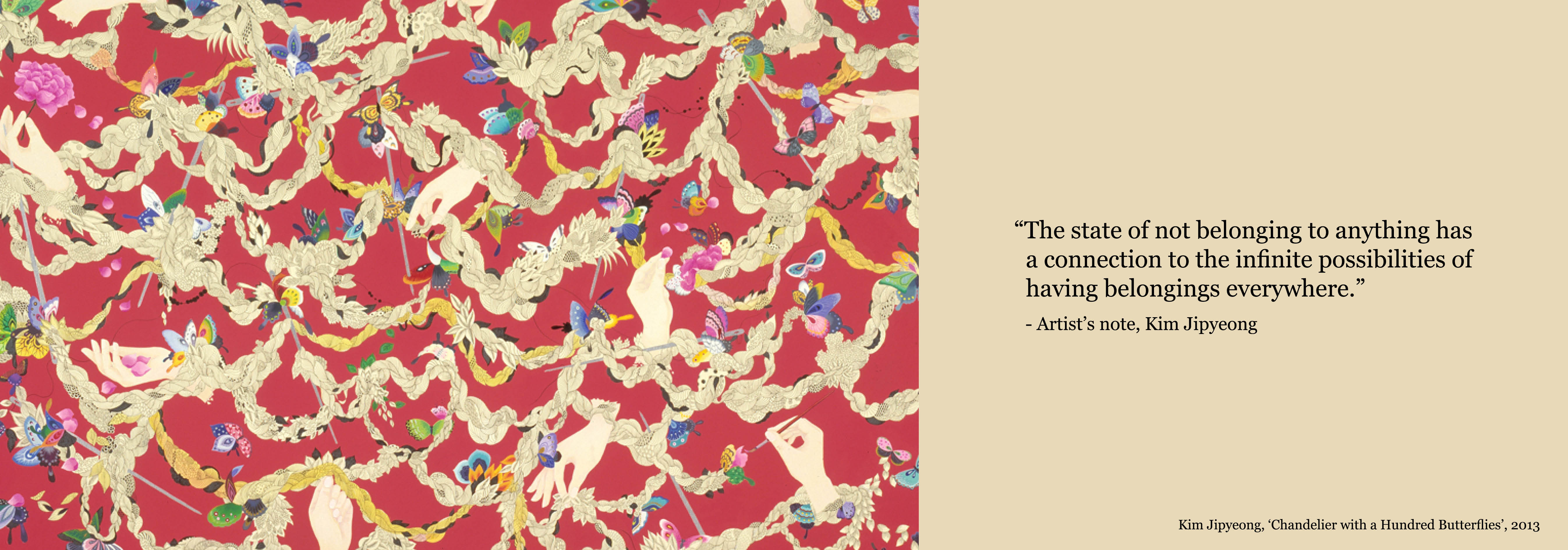

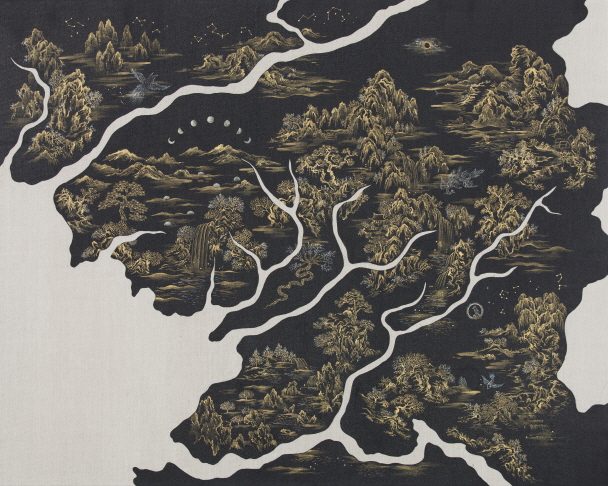

I have been paying more

attention to East Asian values that are homologous to tradition than to the

style or materials of Oriental painting, especially not generalizations about

traditional culture, but rather the various layers of tradition that are unfamiliar

to us or that are at the bottom of our consciousness. Uncovering traditions

forces us to step back and look at contemporary values that are often shaped by

fast trends and fads. With a little change of mindset, the concept of tradition

is not an outmoded convention that binds us to contemporary values. Rather, I

think it can give us the freedom to break free from preconceived notions.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- The titles of the paintings

on display in 'Paintings Lost' – ‘Diva - Goth Singers’ (2023), ‘Diva –

Grandmothers’ (2023), and ‘Diva – Shamans’ (2023) - evoke women's stories and,

by extension, those who have been erased or pushed out of history.

In this exhibition, 'none'

also refers to things that have been erased or forgotten. Therefore, it can

also refer to the status and roles of women in the past. I wanted to erase the

pictures in the folding screen and emphasize only the properties and structure

of the medium to remind us of a new way of looking at it. Most of the works in

this exhibition are an extension of the work I have been doing for several

years, including the 'Diva' series. I questioned the way we perceive the

folding screen by paying attention to its structure and designation, which is

only recognized as a frame for the pictures, but I also had fun playing with

silk cloth and traditional decorations. In a folding screen or a scroll, the

upper part of the screen that is not the picture is called the collar, the

lower part is called the skirt, and the side is called the sleeve. I found it

interesting that they were anthropomorphized by women's clothes or bodies, so I

removed the pictures and imagined the status or role of certain women by their

clothes (skirts, hoops, and sleeves).

The three-wide folding

screen, ‘Diva – Goth Singers,’ was inspired by the idea of three gothic ladies

singing together. I grew up listening to various bands from a young age, and

rock music is generally perceived as a man's music. I wanted to focus on

European gothic female vocalists from the 1980s and 1990s because they were

provocative figures who pushed the boundaries of such conventions, and they

were the ones I looked up to as a child. The ‘Diva - shamans' are the shamans

who chant at traditional goodies, and the 'Diva - grandmothers' are the

grandmothers around us who are dressed in colorful floral patterns from top to

bottom. I hope that even if the viewers don't know this background, they will

see the microphone in front of the folding screen and imagine an act or a stage

where someone is in the spotlight. Between the pictureless folding screen and

the microphone, it's okay for the viewer to think of themselves as the main

character. I hope that the theme of the exhibition, 'Paintings Lost', can be

imagined not only as an image but also as an auditory sensation, such as sound

or song, and resonate with each person's emotions.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- This may seem like a cliché

question, but I'm curious. What made you decide to specialize in oriental

painting in the first place?

I've been doing art since I

was a kid and studied at Seoul Arts High School. I was introduced to oriental

painting in high school, and I was very excited to learn new materials, so I

worked hard and naturally chose oriental painting as my major. However, when I

entered university, I was confused because everything seemed to be in conflict.

It was difficult to reconcile the working methods of contemporary art and

traditional oriental painting that I saw outside of school. After a troubled

undergraduate period, I went to graduate school for education, and through

various experiences, I became interested in 'folk painting' and 'folk art'. By

connecting the folk art of the past with the popular culture of the early

2000s, I gradually laid the foundation for my current work.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- Nowadays, a single artist

can showcase works in different mediums at the same time, but it might have

been harder for me in college because I was trained to work on a flat surface.

What was your first installation and what inspired it?

From the beginning of my

work, I had very few preconceived notions about genre conventions, so I felt

comfortable doing whatever I wanted. For my first solo exhibition 'ViVid Drops

- 色의 淚' (2001), I installed a large cloth printed with my drawings. For

the young artists' exhibition 'SeMA 2004 - 6 Stories' (2004) at the Seoul

Museum of Art, I made a three-dimensional book map with a huge wooden

structure. You've been working as an artist for more than 20 years and don't

limit yourself to your undergraduate experience. I think it's good to work in a

variety of formats, whether it's video or installation, as long as it's

appropriate to express a certain subject. However, it takes research and effort

to be able to utilize the characteristics and concepts of each medium well.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- You are one of the artists

often mentioned when talking about Oriental painting. What does Kim think

oriental painting is?

The question 'what is

Oriental painting' is very difficult to answer. Any definition risks excluding

other values, as Oriental painting or Korean painting is an extension of the

art system established in modern times and reflects the genre conventions of

Korean art. I would like to rephrase the question to 'where is Oriental

painting today'. When we think of what we call Oriental painting now, it seems

that we usually put a lot of emphasis on the use of materials. Nowadays, there

seems to be a tendency to emphasize the importance of the base, which is Hanji,

no matter what kind of paint is used. For example, if an artist actively uses

traditional East Asian concepts or discourse to create oil paintings, we don't

use the word Orientalism. On the contrary, if an artist paints contemporary

current events on a Japanese paper background, it is easy to recognize it as

oriental painting. In my case, a museum has two works in the form of arithmetic

paintings, one painted with acrylic on canvas and the other painted with

pigment on Hanji, which are categorized as Western paintings. They can be found

on the institution's website. I see the duality or ambiguity of these

institutional conventions as a condition and recognize it as a special

situation of Korean art. When I think of it that way, I focus my attention on

how to make good use of those conditions and how to enable new thinking with

the diverse perspectives of contemporary art. Sometimes, the unanswerable

questions surrounding Oriental painting are themselves the work. While it's

important to do good work regardless of material or genre, sometimes it's

necessary to make distinctions to clarify certain concepts. This is because

Oriental painting has its own history, culture, and specificity of concepts and

materials. I think it is necessary to be able to see both narrowly and broadly,

to examine the distance between Eastern and Western art and history, tradition

and contemporary values, while simultaneously embracing the complexity of the

situation.

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

김지평 개인전(Kim Jipyeng Solo

Exhibition) ‘없는 그림 (Paintings Lost)’, 2023. Installation

view, Photo = 홍철기 (Hong Cheolgi) ©김지평(Kim Jipyeong)

- Some people find Oriental

painting too abstract, metaphysical, and distant when they hear about it. There

are many reasons for this, but I think it may be because they are not familiar

with Oriental painting theory or Eastern philosophy. I'd like to hear Kim's

thoughts on this.

In Korea, most of us are

familiar with Western art. It is natural that Oriental painting and Eastern

philosophy and aesthetics come to us late. It took me quite a while to come to

the point where I could enjoy the characteristics of Oriental painting as a

special condition of contemporary Korean art. What comes to mind now that I've

been asked this question are the vague concepts that we often hear when talking

about Oriental painting or traditional art, such as "no-action

nature" and the beauty of the margins. But were these difficult concepts

common even before the modern art system was established and Oriental painting

as a subgenre of art was created? In the past, paintings had a clear purpose,

whether it was for a florist to paint to order, for the great and good to share

and enjoy each other's paintings and poetry, or for religious purposes. There

would have been a language to go along with it. However, I think that the words

we use today to describe Oriental art are either because we are trying to make

sense of Oriental art that has become distant from reality by adopting Western

art, or because there is a lack of effort to elaborate on Oriental art or

tradition. Any art needs the words and texts of the time. If it is separated

from reality in abstract and metaphysical terms, it is difficult to call it a

living art language. If old Eastern theories or philosophies are required, it

will be necessary to refine and translate them into the current vivid language.

- Finally, what would you

like to say to the viewers who encounter your work?

I would like the viewers to

feel the liberation and freedom of art when they encounter my work. It will be

more interesting to see how the values and cultural symbols of different time

periods are interconnected behind individual works.