Before overseas travel was completely liberalized in 1989, the only way for students to experience architecture around the world had been through texts and black-and-white photography. Color photobooks published by some travelers traveling overseas were the best way to view sceneries of foreign cities. At that time, young professors who returned from studying abroad showed works of master architects and these made my heart race. Slide files in a bookshelf of a professor's lab meant academic authority. In the 1990s, architects formed groups and went abroad to explore architecture. Heavy cameras were hung over their shoulders, and their backpack contained dozens or hundreds of slide films.

It has been more than 30 years since then, and only a few architects are taking their cameras out at their new destinations. The architects take a snapshot with smartphones and that is it. I have seen thousands of unscanned images being thrown into a trash can as slide files in the lab of a senior professor who is close to retirement. The same happens both domestically and internationally. Owning images, whether slides or digital files, no longer signifies authority. A huge number of images is circulated on the Internet. A webzine containing new drawings and images created in Africa and South America is delivered daily through smartphones. As long as we don't decide to block, images and information surround our daily lives.

I study cities and architecture using drawings, historical records, and statistics. However, we can immediately approach the reality of a city through a photograph captured intuitively rather than an analytical research. Therefore, we send emails, make phone calls, and do the legwork to find pictures for books amidst the flood of images. This is not only about before the copyright problem, but because we require a picture which projects in a visual form the world of feelings we cannot describe with words and numbers. We have come to the digital age after the ‘age of technological reproduction’ of the early 20th century, but ‘uniqueness’ of photography and the ‘aura’ of an artist are still alive.

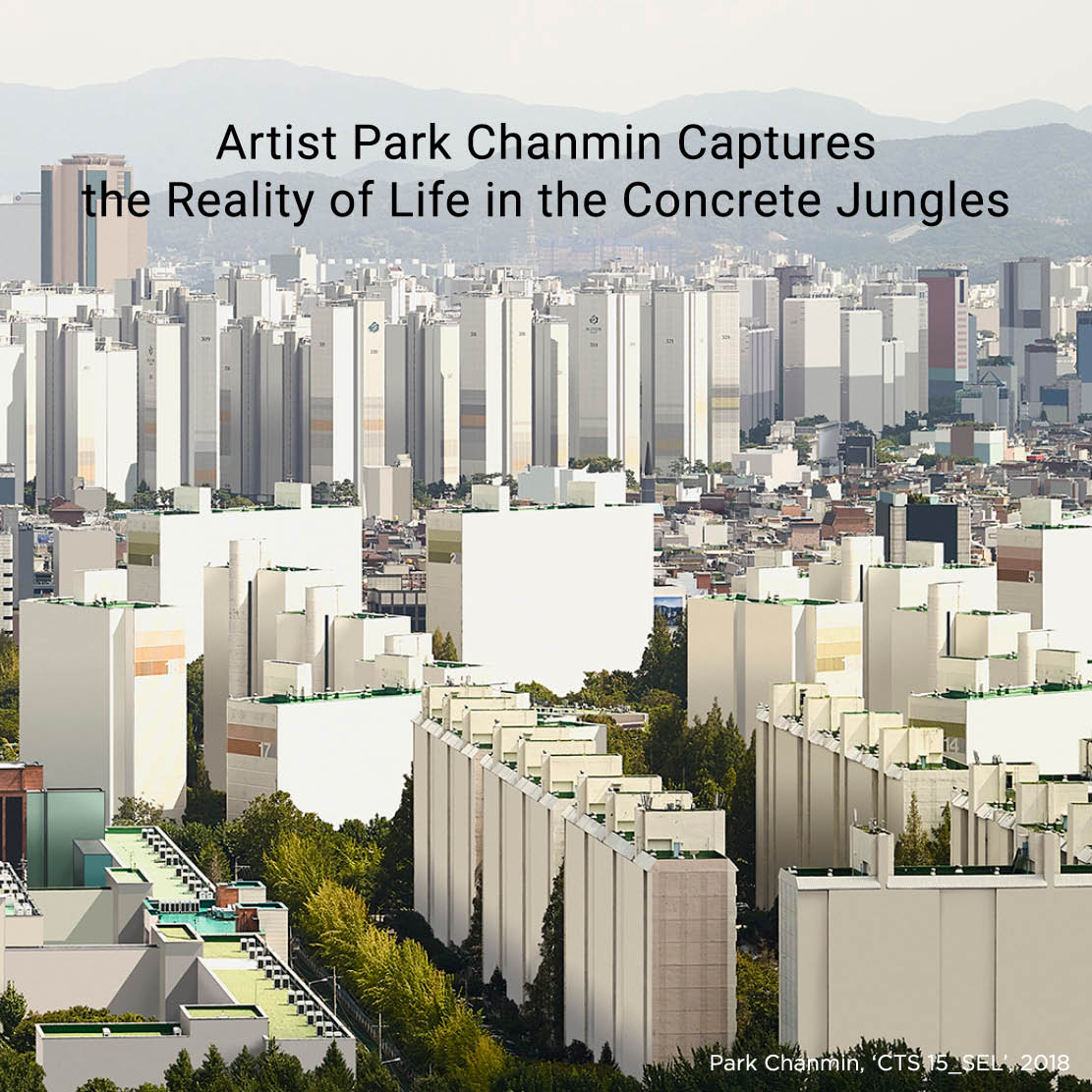

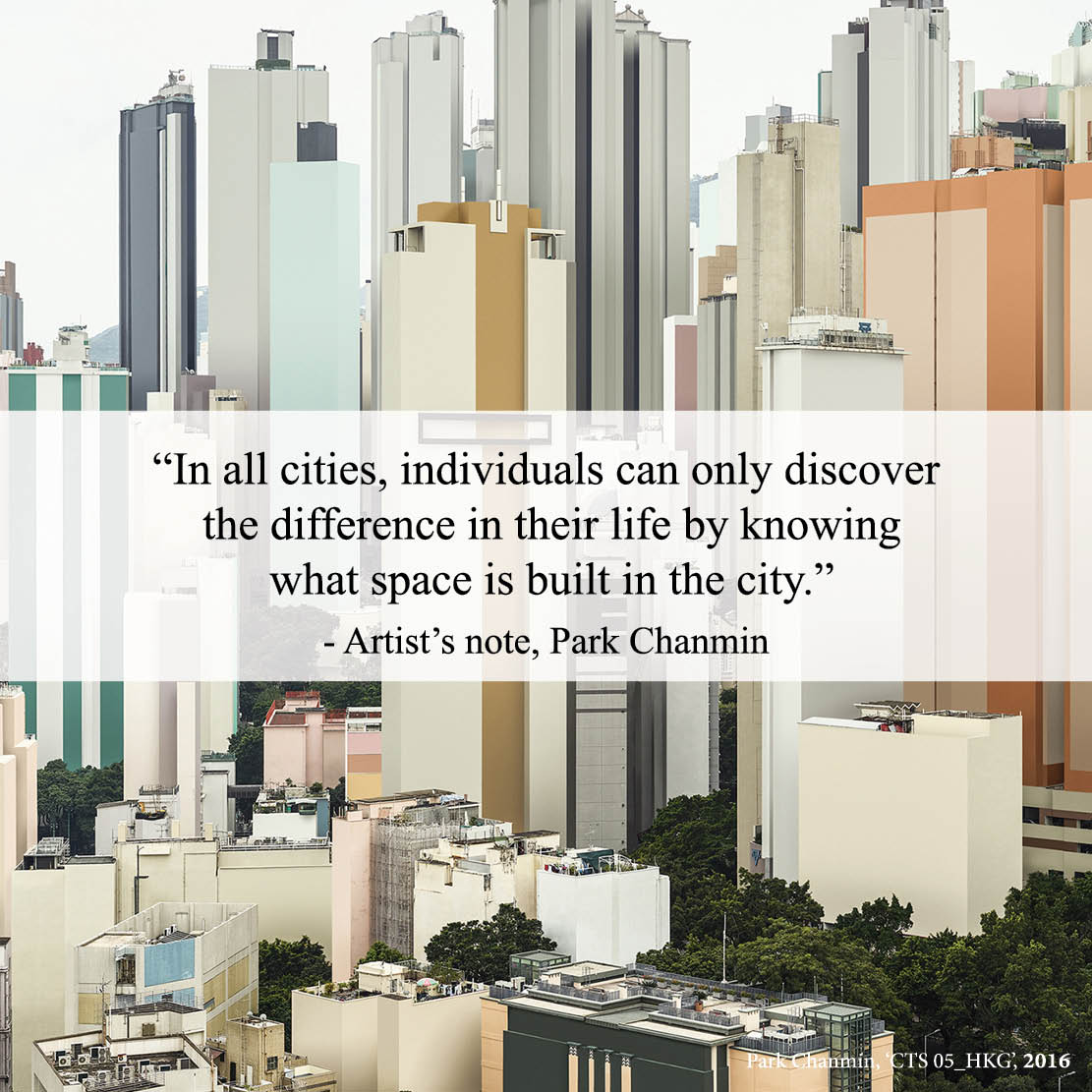

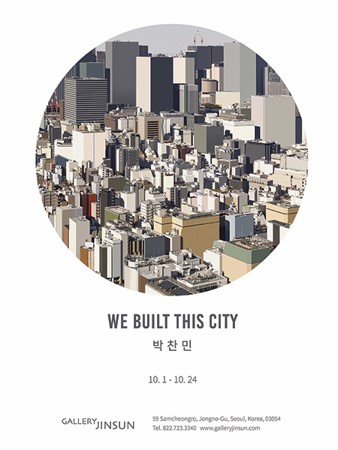

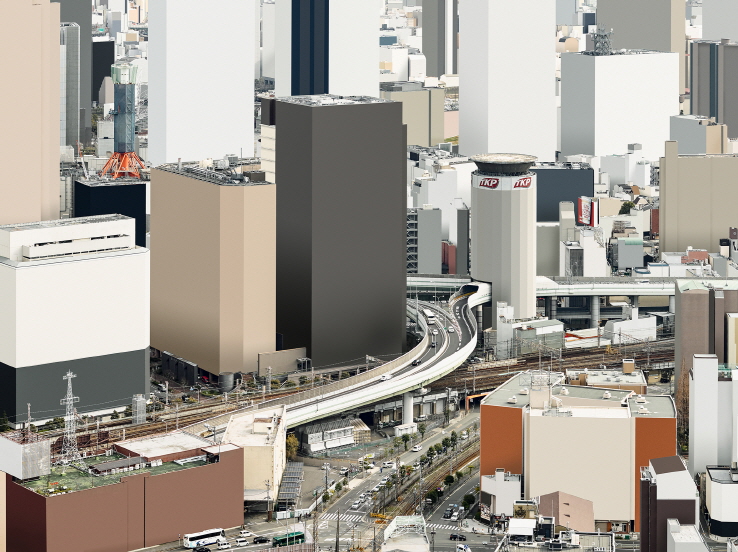

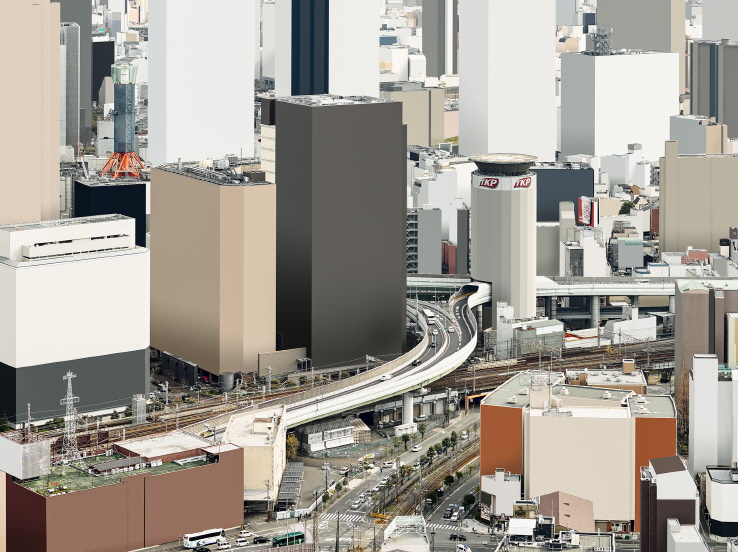

Chanmin Park's new exhibition ‘We Built This City (2021)’ is a work of cities following ‘Intimate City (2008),’ ‘Untitled (2013),’ ‘Urbanscape: Surrounded by Space (2015),’ and ‘Blocks (2015).’ Chanmin Park's photograph, seen through the eyes of an architect, is the middle view of a city where nature has stepped back. To exclude the three-point perspective effect as much as possible, the midpoint between the city surface looking up and the bird's eye view looking down is taken as the vanishing point of the camera. The time of day is around noon when long shadows, sharp contrasts, and diffused light are not present. It is an expressionless urban landscape captured with a telephoto lens, excluding spectacles, dramatic atmospheres, events, and fleeting scenes. The building, where the details of the surface have been removed, remains as a heavy mass. It is like looking at a surreal urban space at noon as if people have been erased from an Edward Hopper's painting.

Chanmin Park expresses this as ‘neutrality of emotions or values’ underneath modern art. The meaning of painting, sculptures, and architecture prior to modernism is not a figure or form itself, but something that they are trying to convey. Modern projects have overturned the relationship between signified and signifier. Art does not represent something outside of art. There only exist constitutive logic, order, and law of figures and forms. The value of an artwork lies not in a medium through which it is communicated, but in itself. However, this does not mean artworks do not represent intentions, meanings, or representations. It means that one narrative structure and one interpretation planted by a creator cannot be established. The one-sided relationship between the subject and the object is turned into a multi-layered and reciprocal relationship.

However, abstruse theories and knowledge are not prerequisites for us who are standing in front of the work to acquire. We do not exclaim after analyzing and interpreting. Our reaction is intuitive and simultaneous. This is because we first communicate in the world of feelings before the world of logic. Even if it cannot be disassembled and analyzed, there is something in Chanmin Park's photograph that fixes the gaze and moves the heart. It is the neutral beauty that remains after unnecessary things are removed.

If you take a close look at the photo book ‘Blocks (2015),’ you can see at a glance that it is a small British town with high latitude where the sun is not scorching and the humidity is high. The reasons are the color of the sky, the surfaces of the buildings and roads, the gloomy nature, and the street corner scenery with few people. On the other hand, it is difficult to tell whether the forest of skyscrapers in ‘Urbanscape: Surrounded by Space (2015)’ is in Hong Kong, Tokyo, or Seoul. The photos with the windows and doors removed are even more difficult to tell.

It is ironic that Asian cities are more modern than the country which has spread modernism around the world over the past 100 years. For Chanmin Park, who studied photography in Seoul and Edinburgh, similarities and subtle differences in Asian cities would have been a more realistic topic than 'oriental fantasy.' The high-rise building masses and silhouettes of the three cities in East Asia revealed in his photos are surprisingly similar. This means there are only differences in details such as wall tiles, letters, outdoor units of air conditioners, and stair railings. This also means that the real difference between East Asian cities lies in the small details, not in the grand and showy landmarks or icons. His photos show that Seoul cannot and does not have to be a European city.

A few photos, drawings, and books can make you a star, but they are not called as artists. The artists are those people who endure boring and endless repetition. In the film about the author of ‘The Catcher in the Rye,’ the teacher asks a young aspirant, “Getting used to being rejected for publication is the first step of an author. Would you still write if you could not publish in your lifetime?” It is such a brutal question. Writing, drawing, and taking pictures are to empathize with someone. But it also has to survive as a profession. an author's There is a fine, paper-thin line between the desire for 'empathy' and the struggle for 'survival,' but completely different worlds unfold on the front and back of paper. The film drags both worlds to the last scene.

Now that YouTube views and Instagram sensibility are overwhelming, the life of a photographer who distances himself from commercial photography and documentary is lonely and precarious. Still, to the question of what drives him to do preliminary research in the studio every day and go out on the street with his camera, He answered, "I don't think about it." Artisans who make their livings by tediously repetitive work do not think with their heads. I believe that the weight and depth are created when the trajectory and work of a human, who has lived fiercely while enduring what has been given, form a single narrative. Chanmin Park's city work for over ten years must have been a tedious and repetitive route to create his own narrative as well.

The new pieces presented in this exhibition ‘We Built this City’ show that his perspective on the cities has become bolder and more intimate. While the subject is narrowed down to our cities in East Asia, the works are looking at the cities from above and the distance. The urban landscapes encompassing buildings, mountains, seas, rivers, roads, bridges, overpasses, and landscapes, are revealed more clearly. The modern cities are collections of desire, competition, conflict, and compromise. Chanmin Park is dissecting them more deeply and sharply.