From April 18 to August 20, 2023, the Suwon Museum of Art is holding a group exhibition entitled So-Called Normal Family to question the perception of normality and normal family in Korean society through the works of 11 artists and groups.

Poster image of "So-Called Normal Family," Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea. (April 18, 2023 - August 20, 2023). Courtesy of the museum.

Poster image of "So-Called Normal Family," Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea. (April 18, 2023 - August 20, 2023). Courtesy of the museum.The form, meaning, and structure of the family have undergone new changes. Lifestyle changes due to industrialization and urbanization are altering the values and meaning of family, marriage, and children. Today, family members do not share the same characteristics as in the past, and various family types are emerging in Korea. However, policies and social notions about families in the country still fail to keep up with these modernized family values, sometimes causing unintentional oppression and discrimination.

The Suwon Museum of Art is holding a group exhibition entitled So-Called Normal Family from April 18 to August 20, 2023, to reflect the existing and changing perception of normality and normal family in Korean society.

The Korean exhibition title 어떤 Norm(all) uses a compound word that combines “normal” and “all” to consider normality and acceptability. The exhibition So-Called Normal Family asserts that all forms of the family should be accepted as normal and not be subject to discrimination, even if they deviate from traditional family norms.

A total of 11 contemporary artists and groups are participating, including Kang Tae Hun, Moon Jiyoung, Park Youngsook, Park Hyesoo, An Ga Young, eobchae, Lee Eunsae, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Critical Hit, Kim Yongkwan, and Minki Hong. These artists address the issues surrounding family through 56 works of various genres, including painting, photography, installation, video, game, and documentary.

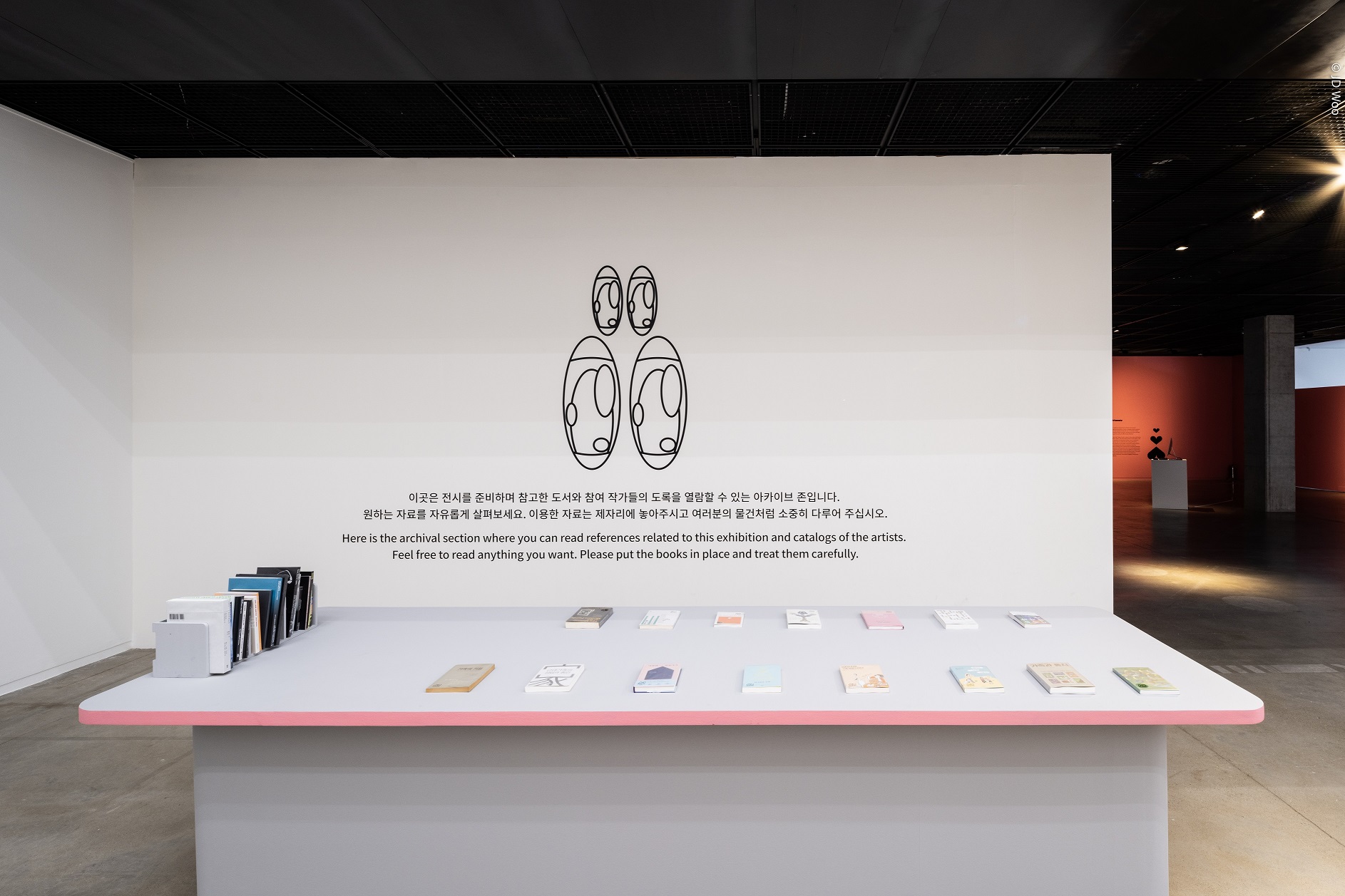

Exhibition view of "So-Called Normal Family," Suwon Museum of Art. (April 18, 2023 - August 20, 2023). Image courtesy of Suwon Museum of Art.

Exhibition view of "So-Called Normal Family," Suwon Museum of Art. (April 18, 2023 - August 20, 2023). Image courtesy of Suwon Museum of Art.The Korean social system is based on the traditional family structure, which focuses on marriage and blood ties. Today, however, the concept of the family is becoming less rigid and taking on increasingly diverse forms. Single-person households, out-of-wedlock births, same-sex marriage, and adoption are becoming increasingly prevalent in contemporary Korean society. Moreover, there is a growing discussion that a living community not bound by social order should be considered and that the Living Partner Act should be reflected in policies.

However, family norms in Korea are still built around the dictionary and legal definitions that reflect the past conception of family. According to the standard Korean language dictionary, “family” refers to a group of people with kinship relations centered on a married couple. Article 3 of Chapter 1 of the Framework Act on Healthy Families defines “family” as the basic unit of society based on marriage, blood ties, and adoption. These norms and systems affect our policies, language, and way of life, unintentionally discriminating against new types of families that exist outside the framework of social norms.

Jang Soo Bin, who curated the exhibition, explained that “this exhibition intends to shed light on how the meaning of family is changing in the reality we face today by borrowing from the perspectives of contemporary artists.” The exhibition consists of three parts.

Part 1 presents works dealing with the various problems behind normal families.

Installation view: Kang Tae Hun, '나쁜 피 (Bad Blood),' 2023, Single-channel video, color, silent, 10 min. 10 sec. Commissioned by the Suwon Museum of Art. Courtesy of the artist and the museum.

Installation view: Kang Tae Hun, '나쁜 피 (Bad Blood),' 2023, Single-channel video, color, silent, 10 min. 10 sec. Commissioned by the Suwon Museum of Art. Courtesy of the artist and the museum.The works of Kang Tae Hun (b. 1975) criticize the political and social ideology derived from the global capitalist system and the structural contradiction of totalitarianism in Korea. By embracing various media such as bricolage, installation art, video, and media, Kang investigates a new world different from this distorted world derived from the existing social system.

In this exhibition, the artist evokes the essence of family through a variety of works that reflect the concerns of many individuals who feel the pressure of marriage or childbirth. The exhibition includes a work that symbolically shows the composition and dissolution of families through overlapping images of red blood cells and family photographs, a work alluding to state atrocities in restricting individual freedom to maintain the population, as well as images and videos that allude to forced marriages. Kang Tae Hun’s works point out the correlation between family and population maintenance and lead us to face the internalized ideology of a normal family.

Installation view: Survey ‘Who Are We’ – the answers of 300 middle-class survey participants, 2019, Survey papers, Dimension variable. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Installation view: Survey ‘Who Are We’ – the answers of 300 middle-class survey participants, 2019, Survey papers, Dimension variable. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Park Hyesoo (b. 1974) collects, investigates, and reconstructs data to raise questions about universal values inherent in our society, such as love, time, and memory. The data, collected through observations, records, and surveys, is presented in various artistic languages, such as installation and video.

In this exhibition, the artist introduces a work created in 2019 using a questionnaire in which 300 middle-class Koreans were asked to describe themselves or the notion of “us.” The survey results of 300 people show that strong familism remains in the consciousness of Koreans. However, another video work that contains the stories of the elderly who died alone and abandoned reveals the contradiction of family ideology in Korea.

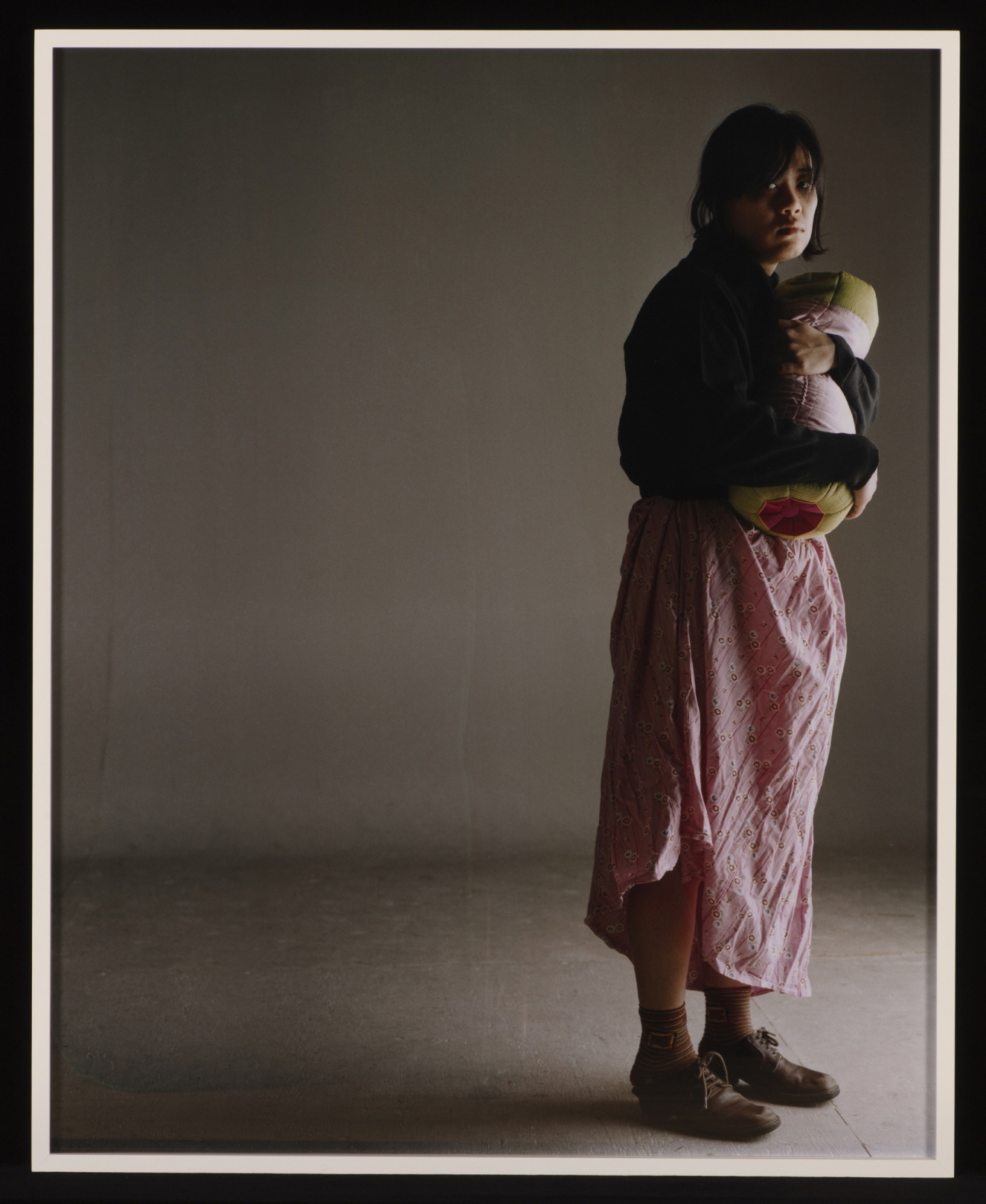

Park Youngsook, 'MAD WOMEN'S #1 (미친년들 시리즈#1)', 1999, C-Print, 150×120 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Park Youngsook, 'MAD WOMEN'S #1 (미친년들 시리즈#1)', 1999, C-Print, 150×120 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Since the 1980s, Park Youngsook (b. 1941) has been known for her photography works that expose the reality of women in Korean society through provocative portraits. The exhibition includes Park’s MAD WOMEN’S series. As the Korean title suggests, the women in the photographs are acting somewhat erratically. Park depicts women as independent, resistant beings who lack the image of a wise mother and wife and instead resemble rebellious characters who defy patriarchal norms.

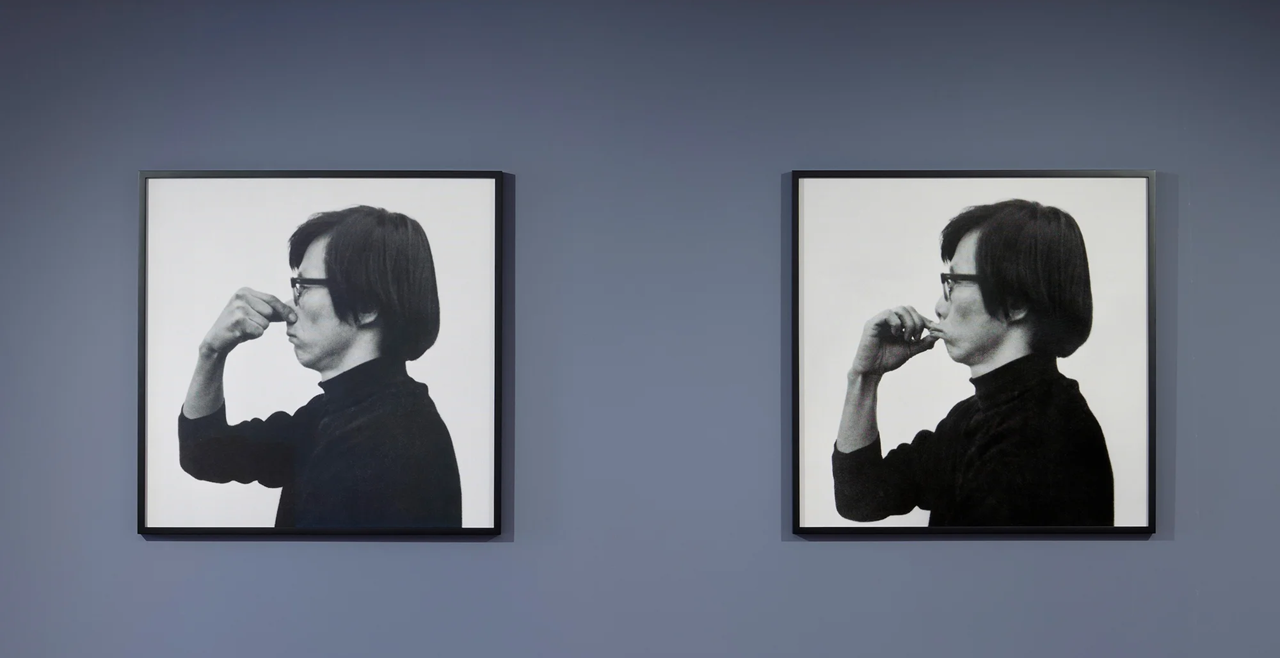

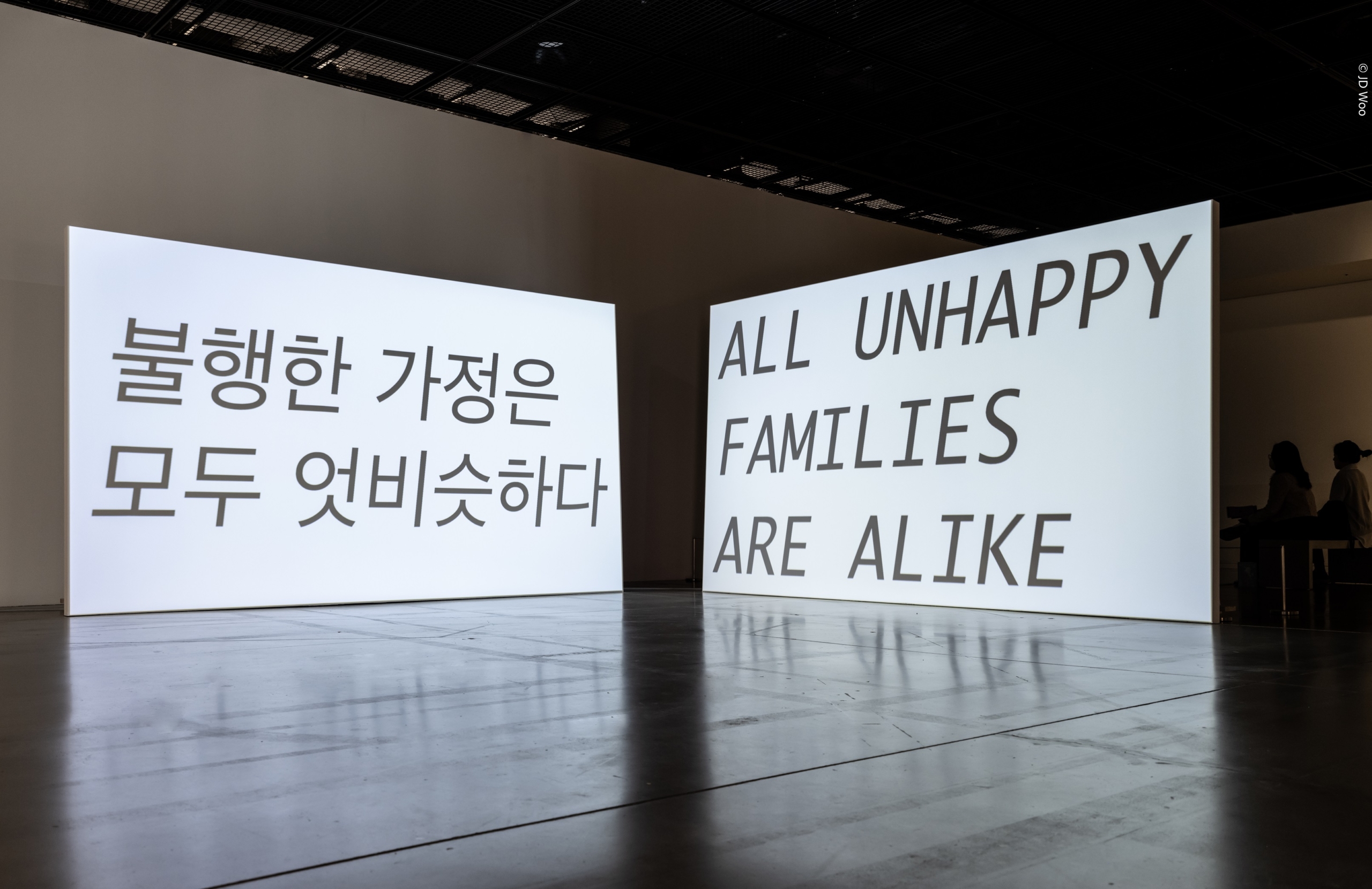

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, 'All Unhappy Families Are Alike (불행한 가정은 모두 엇비슷하다),' 2016, 2-channel video, black and white, sound, 5 min 41 sec, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, 'All Unhappy Families Are Alike (불행한 가정은 모두 엇비슷하다),' 2016, 2-channel video, black and white, sound, 5 min 41 sec, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (f. 1999) is a media artist duo formed by Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge. The duo has been working on web art and is well-known for its text-based works dealing with social issues, which include animation effects and music.

In the exhibition, a typography video titled All Unhappy Families Are Alike is being screened. The video begins with a scene of a family and their relatives gathering for a meal, just like on a Korean holiday. However, as soon as someone brings up the topic of money, the family gathering gradually turns into a mess filled with harsh profanity. The more dynamic the story progresses, the faster the tempo of the music, which eventually reaches its climax when physical violence occurs at the gathering. The work reveals the problems of domestic violence and discord that exist behind the facade of the typical family.

Part 2 reveals the existence of minorities who are often alienated from our society’s normal family categories.

Moon Jiyoung, '반야용선 (banyayongseon),' 2023, Oil on canvas, 112x145 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Moon Jiyoung, '반야용선 (banyayongseon),' 2023, Oil on canvas, 112x145 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Moon Jiyoung’s (b. 1983) works reveal society’s prejudice against disability and disease as well as its indifference toward minorities. Through paintings and installations, Moon particularly expresses the lives of women in patriarchal societies who have the responsibility to care for others.

The artist portrays images of a mother who earnestly relies on religion for the complete recovery of her disabled child. The image contains repeated religious icons and messages of faith in blessings. Moon’s works reveal the reality of those who have no choice but to exist as weak members of society because they cannot overcome the wall of normality.

Lee Eunsae, '짐 싣는 사람들 (Loaders),' 2019, Oil on canvas, 218.2×290.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Lee Eunsae, '짐 싣는 사람들 (Loaders),' 2019, Oil on canvas, 218.2×290.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Artist Lee Eunsae (b. 1987) reflects her resistance to Korean society through her paintings. The artist depicts personal experiences of Korean society and the rebellious imagination felt through popular culture or social media using simple, bold brush strokes and original color combinations. Various types of families outside the category of traditional family forms, such as single-person households, single-parent families, families with pets, and cohabiting families, appear in her works, revealing that their lives are not very different from those of other families.

Critical Hit, '종이 아래 (Under the Paper),' 2022-2023, Acrylic, water color, crayon on paper, 51×36 cm (12 each). Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Critical Hit, '종이 아래 (Under the Paper),' 2022-2023, Acrylic, water color, crayon on paper, 51×36 cm (12 each). Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Critical Hit (b. 1988) depicts the various lives of minorities through drawings, paintings, and video works, revealing the challenges they face and their exclusion from mainstream society. The exhibited video series Sylvanian Familiarism features toy animals portraying various minorities, including those with HIV, disabilities, LGBTQ refugees, and disaster victims, forming a community where they all live together. Another series, Under the Paper, shows the reality of the underprivileged, who can only prove themselves with documents, revealing our society’s inequality and disregard for the socially underprivileged.

Minki Hong, 'I Smell Wedding Bells,' 2021, Single-channel video, color, sound, 39 min 45 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Minki Hong, 'I Smell Wedding Bells,' 2021, Single-channel video, color, sound, 39 min 45 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Minki Hong (b. 1992), an LGBTQ artist living in South Korea, uses the video to show how the diversifying digital environment affects our society. Recently, Hong has been creating experimental documentaries that reveal the hidden histories of LGBTQ individuals in Korean society from the 1970s to the present.

I Smell Wedding Bells is a documentary work about Minki, a gay man, and his partner, as they face legal hurdles regarding marriage and visas, whereas his older brother benefits from the social stability provided by marrying his girlfriend. The documentary explores the experiences of a heterosexual family coming to understand what it means to have a queer family member.

Part 3 shows the possibility and hope for a new type of family to emerge in Korean society.

An Ga Young, '히온의 아이들: 우리의 영혼을 받아주소서 (Heeon's Children),' 2023, Machinima, FHD color, 15 min 15 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

An Ga Young, '히온의 아이들: 우리의 영혼을 받아주소서 (Heeon's Children),' 2023, Machinima, FHD color, 15 min 15 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.An Ga Young (b. 1985) creates various characters within virtual space using games and metaverse platforms to explore new possibilities of the body or present an alternative life as a woman.

The work introduced in the exhibition imagine the symbiosis of various species that may exist in the future. Through the interaction between human and non-human species, the artist reveals the absurdities of anthropocentrism, patriarchy, and capitalism in reality while simultaneously conveying a message of symbiosis.

eobchae, 'nahee.app run daddy.app,' 2019, Single-channel video, color, sound, 11 min 15 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

eobchae, 'nahee.app run daddy.app,' 2019, Single-channel video, color, sound, 11 min 15 sec. Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.An audio-visual group, eobchae (f. 2016), was founded by Nahee Kim, Cheon-seok Oh, and Hwi Hwang. Through their work, eobchae transcends traditional boundaries of media, incorporating video, web-based programming, sound, and performance to create a worldview that meshes with the accelerating digital environment and, furthermore, sheds light on the perspectives we overlook in the process. The exhibition features four video works related to the Daddy Residency project, which seeks a partner to raise a baby that will be born through artificial insemination to one of the group members in 2025.

Kim Yongkwan, '무지개 반사 (rainbow-reflection)', 2023, UV print on sheets, Dimension variable, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.

Kim Yongkwan, '무지개 반사 (rainbow-reflection)', 2023, UV print on sheets, Dimension variable, Courtesy of the artist and Suwon Museum of Art.Kim Yongkwan (b. 1980) utilizes scientific and mathematical systems to develop his artistic practices, which include paintings, sculpture, installation, and design. The artist creates images with visual elements reminiscent of geometry or programming by comparing mathematical concepts such as points, lines, planes, shapes, patterns, modules, and tessellations. The exhibited group of works, including the wall and installations of various shapes, are covered in rainbow colors. The various colors in Kim’s works symbolize the various beings living in our society. This is a metaphor for the utopia imagined by the artist, an ideal world in which diversity coexists.