Korean experimental art (“silheommisul”) is gaining recognition both within Korea and on the international stage. But what exactly is Korean experimental art?

Lee Seung-taek, ‘Wind-Folk Amusement,’ (1971). Courtesy of Lee Seung-taek, Asian Culture Complex and Gallery Hyundai.

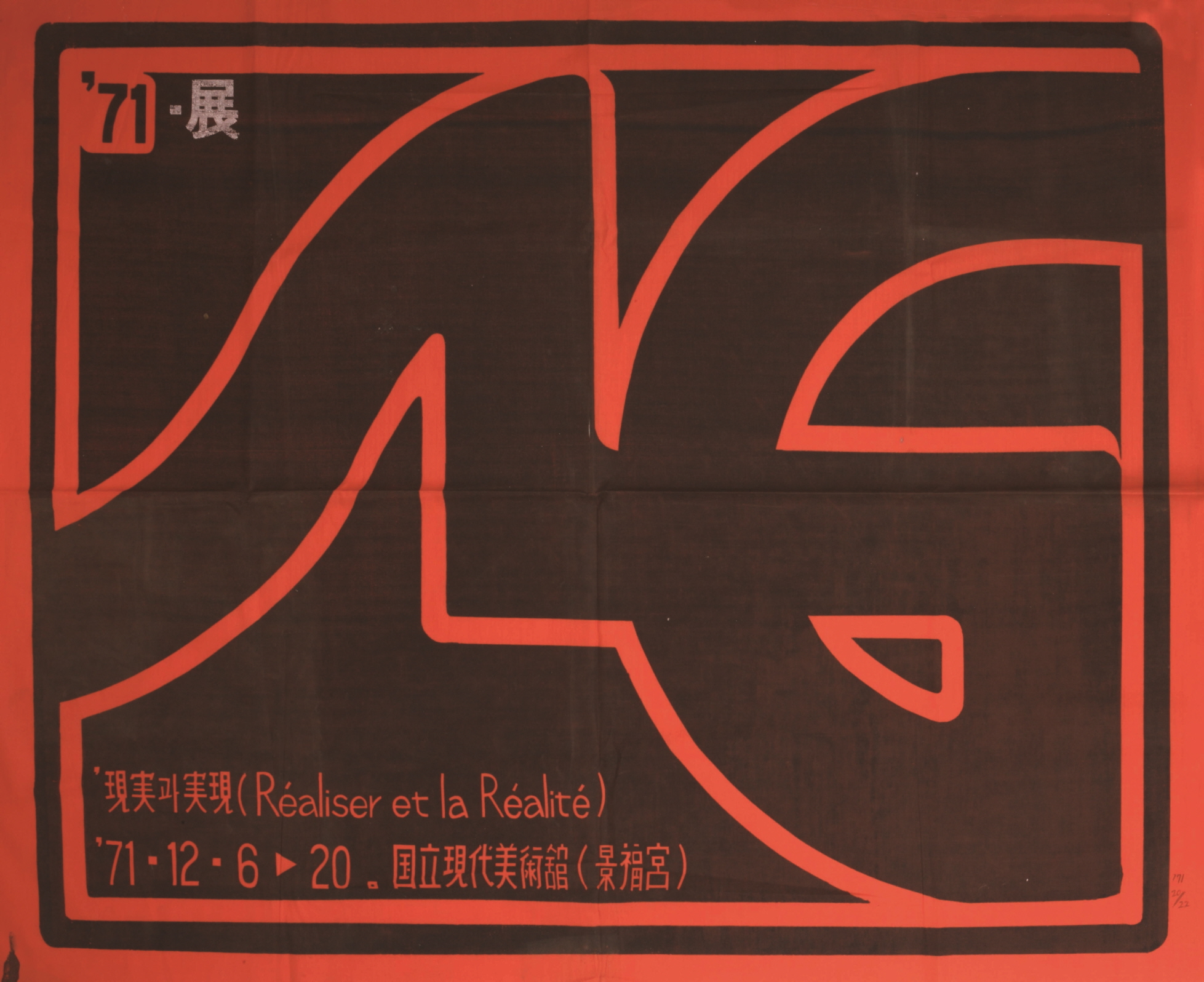

Lee Seung-taek, ‘Wind-Folk Amusement,’ (1971). Courtesy of Lee Seung-taek, Asian Culture Complex and Gallery Hyundai.Korean experimental art has recently been gaining considerable attention. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York collaborated to organize Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s. The exhibition just wrapped up its run in South Korea and is now traveling to the United States. The mega gallery Pace’s New York branch, with locations worldwide, is currently showcasing a solo exhibition by artist Lee Kun-Yong until August 18, and Lehmann Maupin New York is planning to hold a solo exhibition by artist Sung Neung-kyung in September.

Those unfamiliar with the term may find it difficult to comprehend the nature of Korean experimental art, which is often in the public eye both locally and internationally. Some people may even shake their heads at the idea of experimental art, believing it to be esoteric and complicated. Such a viewpoint might indeed be valid.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.In 1971, Lee Kun-Yong brought forth a statement piece, Corporal Term (1971), by placing a tree uprooted from the Gyeongbu Expressway inside an art museum. Similarly, in 1970, Kim Kulim presented a performance titled From Phenomenon to Traces, in which he conducted a funeral ceremony while draping a white shroud around a museum, symbolizing established art. Kang Kuk-jin, Jung Chan-seung, and Jung Kang-ja showcased the participatory performance Transparent Balloons and Nude (1967), where they popped transparent balloons attached to a nude body to expose the male perspective’s fantasy interpretation of the female figure.

Upon viewing these pieces, one might raise a mental question mark, wondering, “Is this also considered art?” That could very well be the case. In fact, when these works were first presented, the media labeled them “bizarre and crazy,” “funny,” or simply ignored them.

However, if we comprehend the historical context and significance of the emergence of experimental art, we might find enjoyment in appreciating these artworks. Experimental art embodies the concept of “avant-garde,” signifying innovation and radicalism. Korean experimental art emerged against the distinct backdrop of Korea during the 1960s and 1970s. These artists pursued novelty and innovation amid the turbulent Korean situation, engaging with societal issues and transcending boundaries between diverse artistic fields such as performance, literature, and music.

Installation view of "Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s" at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). Courtesy of the MMCA.

Between the 1960s and 1970s, experimental art rose in the context of modern Korean art history, particularly as a critique of the established art system. In an era when abstract painting dominated the Korean art scene, experimental artists sought novelty in terms of medium, form, and content.

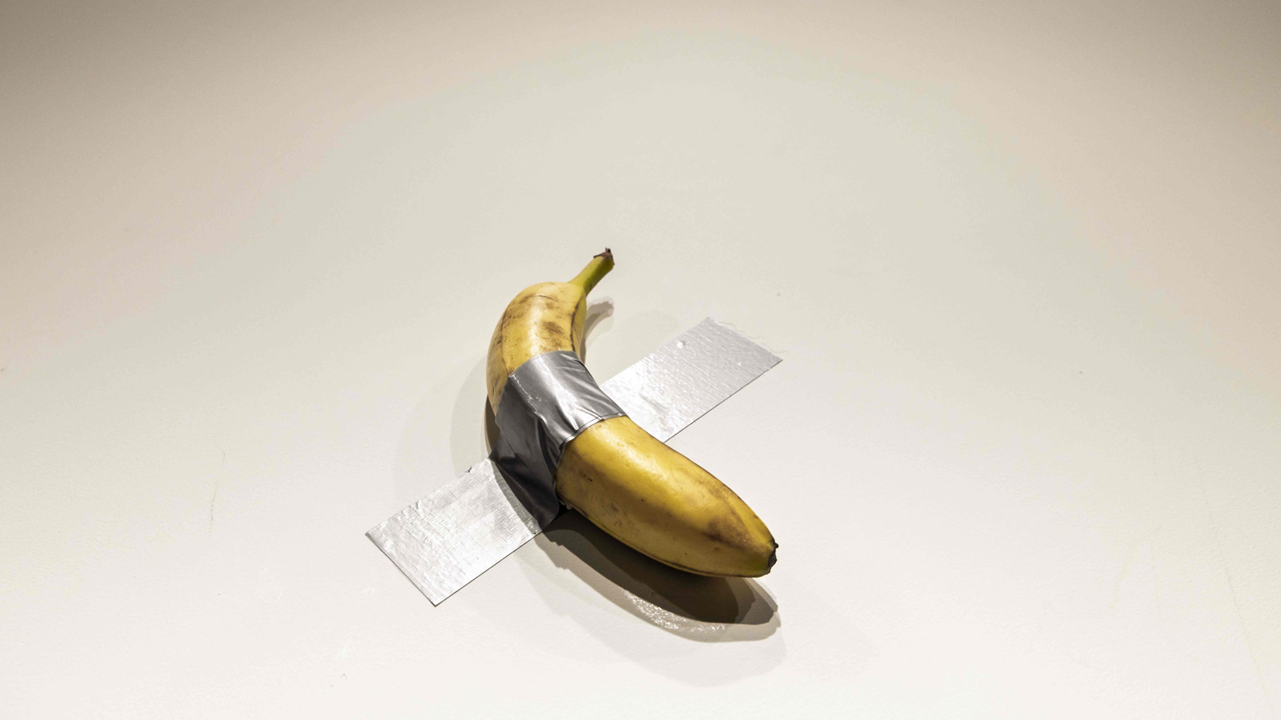

Regarding medium and form, experimental art expanded beyond traditional painting and sculpture, incorporating new mediums and forms such as objects, installations, happenings, and video. When it came to content, it embraced a Dadaist spirit, advocating for irrationality, anti-logic, and anti-art and challenging existing values and orders.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.Recent interest in Korean experimental art can be attributed to a number of factors, but one of the most significant is that it fills a gap within the broader flow of Korean contemporary art history. Korean experimental art has long been overlooked in the local contemporary art scene. Until recently, it has not been adequately categorized or recognized as a unified movement.

The emergence of the Art Informel movement, which opened the door to contemporary Korean art history, swept through the Korean art scene with great popularity. Subsequently, Dansaekhwa (Korean monochrome art), which appeared after Korean experimental art, also dominated the Korean art scene for an extended period. However, during this time, the emergence of Korean experimental art was viewed as a confusing, disjointed, or stagnant phase in the art world.

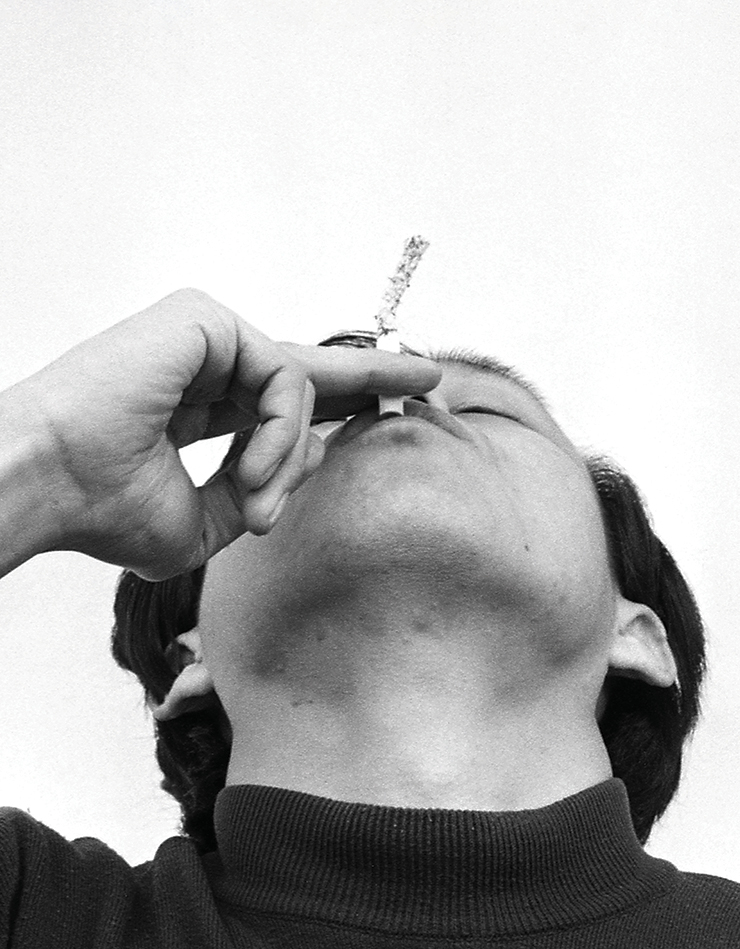

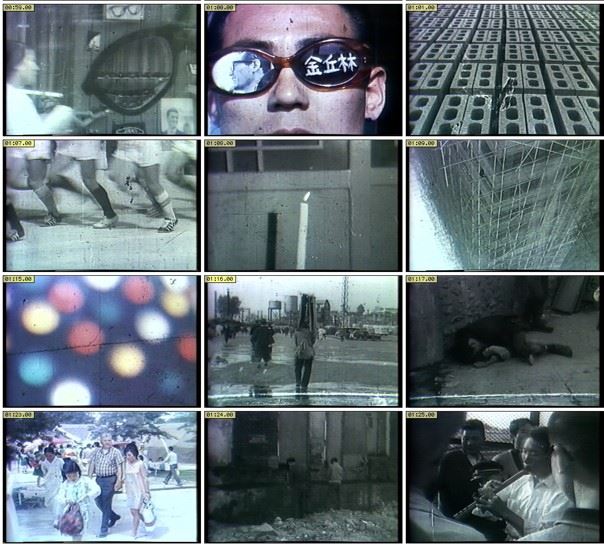

Still images of Kim Kulim's ‘The Meaning of 1/24 Second’ (1969). Courtesy of the artist and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea.

Still images of Kim Kulim's ‘The Meaning of 1/24 Second’ (1969). Courtesy of the artist and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea.Unlike the Art Informel or the Dansaekhwa movements, Korean experimental art was not privileged with the same degree of governmental support or public comprehension. Instead, it encountered various oppressions and dismissals, struggling to unfold and often relying on small groups or individuals to lead, resulting in mostly sporadic and short-lived activities.

Why did Korean experimental art remain in the shadows for so long? Examining the social context of the time provides an easy explanation. During the 1960s and 1970s, South Korea was grappling with military dictatorship and authoritarian governance. In addition to restricting anti-government expressions, the government established by the dictatorship also curbed academic freedom and student actions within universities. Concurrently, Korean experimental art, which aimed to criticize the established art system supported by the government, was stigmatized as subversive art and faced strict regulation.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. (May 26, 2023 – July 16, 2023). Photo by Aproject Company.The 1960s and 1970s in South Korea, which pursued economic development, were marked by rapid population growth and economic hardship, including food scarcity. Alongside these challenges, the artists had to navigate government oppression and public misunderstandings of new art forms. During this time, the government declared a state of emergency, which hindered the possibility of holding experimental art exhibitions. Even if such exhibitions were organized, the means to garner audience attention were obstructed. As a result, these artists resisted the established art system, but their efforts could not be sustained due to a lack of solid political agendas and difficulties in forming cohesive groups.

However, similar to the Art Informel movement, Korean experimental art was influenced by various movements in Western countries and Japan. Despite the harsh circumstances, Korean experimental artists resisted the institutionalized art scene driven by the government. They integrated influences from Western movements, including Op Art, Pop Art, and Neo-Dada, adapting and tailoring them to fit the unique context of Korean art.